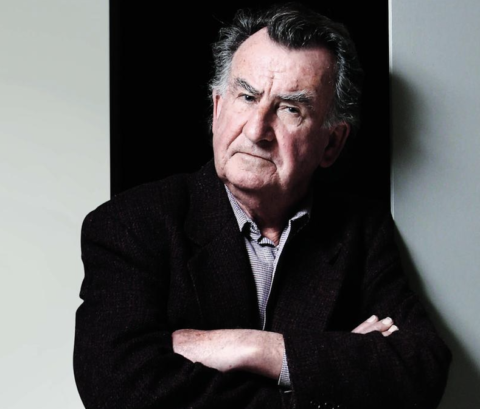

Australian writer Gerald Murnane has been variously described as an oddball (Ryu Spaeth in The New Republic) and a recluse (Merve Emre in The New Yorker). He himself does little to dispel this impression. In his essay “The Breathing Author,” he lists his oddities: he has never been on an aeroplane, never worn sunglasses, does not understand the international date line or exchange rates, has never owned a television set, and has devised a lengthy archive of his own work and manuscripts. At a conference on Murnane held in the small Australian town of Goroke, he was the bartender. It’s nice to see the revival of the genius wacko archetype.

His fiction also shores up this strange mythos. Critic Emmett Stinson has described Murnane as a “homemade Avant Garde of one.” Consider Inland, his fourth novel. It opens with a strange and jarring metafictional conceit. The text we are reading is a letter to the narrator’s editor who edits Hinterland (a term once removed from inland), a journal dedicated to studying prairies and plains, published by the impossibly named Calvin O. Dalhberg Institute located in the impossibly named town of Ideal, South Dakota. His editor is the impossibly named Anne Kristaly Gunnarsen and her husband is the even more impossibly named Gunnar T. Gunnarsen. Reading Murnane is much like reading Kafka — one must remember to laugh.

His fiction also shores up this strange mythos. Critic Emmett Stinson has described Murnane as a “homemade Avant Garde of one.” Consider Inland, his fourth novel. It opens with a strange and jarring metafictional conceit. The text we are reading is a letter to the narrator’s editor who edits Hinterland (a term once removed from inland), a journal dedicated to studying prairies and plains, published by the impossibly named Calvin O. Dalhberg Institute located in the impossibly named town of Ideal, South Dakota. His editor is the impossibly named Anne Kristaly Gunnarsen and her husband is the even more impossibly named Gunnar T. Gunnarsen. Reading Murnane is much like reading Kafka — one must remember to laugh.

Inland first appeared in Australia in 1988, published by William Heinemann Australia. It was Murnane’s last novel until 2009’s Barley Patch, a book about an author who is considering giving up writing fiction. Murnane did publish a book in 1995, Emerald Blue, which is not a novel but a short story collection. 1995 was also the year Ivor Indyk founded Giramondo Publishing Company which published Barley Parch, with whom Murnane would write a novel every few years – History of Books (2012), A Million Windows (2014), Border Districts(2017) — until he announced his retirement from writing (first in 2017, and then again in 2021). Giramondo also reissued Inland in 2013. The new US edition of Inland is also a reissue. Inland appeared in the US in 2012 with Dalkey Archive Press. Second-hand copies of that edition now sell for between $60-80 online. The Dalkey Archive Press edition of Inland is itself a reissue of a Faber and Faber edition from 1989 – that was, as far as I can tell, available in the US – which sells online for around $200.

These reissues and price points hint at the steadily growing reputation of Murnane in the United States. In the dark bars where writers convene, stories abound about Australian cousins shipping antipodean editions of Murnane unavailable north of the equator into grimy NYC mailboxes. Murnane’s fiction has been reviewed in the New York Times, of course, but also taken up in the pages of The Baffler, The Chicago Review of Books, and Commonweal. His oddness, in terms of both his person and his fiction, is part of what appeals to us. He is, no doubt, an excellent writer. In Last Letter to the Reader, his most recent and supposedly final book, he claims that he is the best sentence writer in Australia — a pompous remark if from other writers, but Murnane might just be reporting the truth.

Murnane’s technical excellence as a writer carries his reader across the spare and perplexing itinerary of his novels. Inland’s only major plot development is a moment of paranoia. As the narrator’s letter continues, the addressee – who is also, of course, us — shifts. Our narrator suspects that his editor has been usurped by a jealous husband who despises him.

This is intrigue, of sorts. It is just barely a plot, lacking detail, twists, and turns. There is an indistinctness to it. This quality carries through Murnane’s descriptive language. His images are peculiar but vague. Names are often not used, there are “some men” or “a woman,” usually young. Things are “of a certain kind.” In The Plains, Murnane’s most well-known novel and the one widely considered his best, he offers this description of said plains: “the plains that I crossed in those days were not endlessly alike. Sometimes I looked over a great shallow valley with scattered trees and idles cattle and perhaps a meagre stream at its centre.” That’s it, we hear nothing more about the plains that were not “endlessly alike.”

Sparseness is no barrier to good prose, but the vagueness of Murnane’s descriptions is at odds with how visual he often is. Border Districts, his most recent work of fiction, is an extensive meditation on light. Murnane is an imagist, in the literal sense. In his novels there is an awful lot of looking. Descriptions are vivid but not lurid.

Sparseness is no barrier to good prose, but the vagueness of Murnane’s descriptions is at odds with how visual he often is. Border Districts, his most recent work of fiction, is an extensive meditation on light. Murnane is an imagist, in the literal sense. In his novels there is an awful lot of looking. Descriptions are vivid but not lurid.

There is a passage in Inland that exemplifies this:

“That man has learnt nothing from looking into eyes. He sees in eyes nothing that he has not seen long before. Yet he goes on looking for a face of a certain kind and he goes on writing that he would like to look through the eyes of that face as though an eye is a window. He goes on looking for a face and he goes on writing as though the eyes of the face are the windows of a room with books around its walls, and in that room a young woman sits writing.”

A face of a certain kind? What does this room or these books look like? What does this young woman look like? This does not so much present a clear image as a peculiar one. And this is a quintessential Murnanian image — self-reflexive, a look at looking.

In a 2015 profile of Gerald Murnane, An Idiot in the Greek Sense, Shannon Burns takes issue with the claim that Murnane is a weirdo. There is, of course, a sense of irony to Murnane’s above cited confessions of weirdness. Does it really matter that Murnane hasn’t worn sunglasses? Never been in an aeroplane? It is true that Murnane has his oddities, but the idea he is properly reclusive may be hyperbolic. Much of Burns’ piece is an attempt to dispel the notion that Murnane is so odd that he stands apart from the world. Murnane’s fiction often feels like it takes place in another world entirely. Both The Plains and Inland seem part of some alien world, whose narrators do not seem to have entirely human concerns.

This alienness is undermined by the emotional potency of Inland. Murnane’s works are often quite moving. As Inland comes to a conclusion, the world of the Gunnarsens and Ideal are left behind. The narrator’s recollections recall a high school sweetheart, “the girl from Bendigo Street” (not to be confused with “the girl from Bendigo”) and the novel’s closing scenes find our narrator wandering the cemetery near where he grew up, between Merri and Moonee Ponds in Melbourne, Australia. There he recalls, but cannot find, the grave of the girl from Bendigo Street’s brother. The novel closes with our narrator in a graveyard, weeping. Somehow, out of Murnane’s playful novel an entirely human moment has crept up on us. It is a moment that also occurs in The Plains: the narrative has overtaken the narrator, he has succumbed to his own devices. We recognise this as tragedy, of sorts.

We will find that Murnane’s strangeness is human and that there are good reasons for it. The first section of Inland ends with a truly extraordinary sentence. The narrator has decided that the reader of his text can no longer be Anne Kristaly Gunnarsen but the horrid Gunnar T. Gunnarsen. And so he ends with a warning to his new reader: “driven by the plainness of his native district to look deeply into any place admitting of penetration, my enemy will ponder my prose well.” This sentence, however, is basically a key to Murnane’s work as a whole. How could I capture something like a plain or prairie in vivid prose? What is the description of vastness? And how could I convey the experience of my looking to someone else. How could I describe not just a vast expanse of nothing – a dominant image of the Australian countryside to be sure – but the experience of looking at this nothing?

The heart of Murnane’s work is the intersection of this question and that of looking at looking. The metafictional conceit of Inland is a mirror to this question. Likewise, the narrator of The Plains has come to make a film about the plains. The voyeuristic qualities of Murnane, especially his passages on women, also fall under this rubric. The same eye washes over a landscape and yearns after an inaccessible beauty. This vastness, this looking occur in one other place as well. When we reminisce, looking back on the details of our life, they can stretch out into a vast horizon. Everything is simultaneously near and far. The melancholy of memory and the vastness of the plains fall together in Murnane’s work.

The heart of Murnane’s work is the intersection of this question and that of looking at looking. The metafictional conceit of Inland is a mirror to this question. Likewise, the narrator of The Plains has come to make a film about the plains. The voyeuristic qualities of Murnane, especially his passages on women, also fall under this rubric. The same eye washes over a landscape and yearns after an inaccessible beauty. This vastness, this looking occur in one other place as well. When we reminisce, looking back on the details of our life, they can stretch out into a vast horizon. Everything is simultaneously near and far. The melancholy of memory and the vastness of the plains fall together in Murnane’s work.

If Murnane is strange to us, it is because looking is itself a strange activity, one that produces all kinds of unusual inversions as the familiar becomes unfamiliar. In The Breathing Author, Murnane tells us that he becomes “confused, or even distressed, whenever I find myself among streets or roads that are not arranged in a rectangular grid.” He withdraws from all other activity in order to find his bearings which “takes much mental effort.” Out wandering in a wide indistinct plain, one might find their sense of distance and time fall away. There is something vivid about this nothingness. On a quite sunny afternoon one may find themselves lost in the pathways of recollection, wandering the halls of remembrance misremembered. It is in this space where our orientation slips, where we must shield our eyes, that Murnane’s fiction sits, compelling and strange.

[Published by And Other Stories Press on January 9, 2024, 204 pages, $19.95 US paperback]