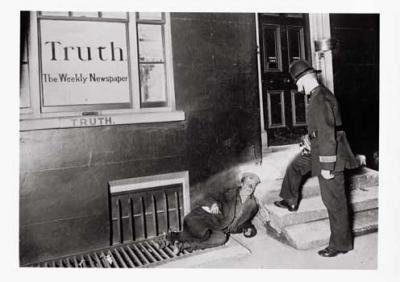

Jack London’s fame was assured when he sold The Call of the Wild to Macmillan in 1903 for today’s equivalent of $15,000. Yet that year also saw the publication of The People of the Abyss, London’s extraordinary photojournalistic narrative of poverty in London’s East End. Impersonating a runaway American sailor, London rented a small room, bought some used clothes, and walked the streets. His disguise and manner must have obscured the intrusion of his Kodak 3A, a postcard-format roll-film folding camera. He photographed drunken women fighting, children dancing to a street organ, and men sleeping under the arches of bridges in the raw cold.

The People of the Abyss anticipates the Margaret Bourke-White and Erskine Caldwell collaboration You Have Seen Their Faces and Bill Brandt’s A Night in London (both published in 1938), not to mention the Evans/Agee masterpiece Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Through a blessing of great timing, London became a major contributor to (and beneficiary of) the early boom in mass media and the rise of photojournalism. The first American magazine to be based primarily on photography, the Illustrated American, appeared in 1890. Yet we have had only a vague impression of London’s photographic accomplishments or the scope of work among the more than 12,000 images he produced. Until now. For the illuminating Jack London, Photographer, Philip Adam made silver gelatin prints from scanned originals, reproduced as duotones in this book.

The People of the Abyss anticipates the Margaret Bourke-White and Erskine Caldwell collaboration You Have Seen Their Faces and Bill Brandt’s A Night in London (both published in 1938), not to mention the Evans/Agee masterpiece Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Through a blessing of great timing, London became a major contributor to (and beneficiary of) the early boom in mass media and the rise of photojournalism. The first American magazine to be based primarily on photography, the Illustrated American, appeared in 1890. Yet we have had only a vague impression of London’s photographic accomplishments or the scope of work among the more than 12,000 images he produced. Until now. For the illuminating Jack London, Photographer, Philip Adam made silver gelatin prints from scanned originals, reproduced as duotones in this book.

Mark Twain may have been the most widely photographed American of his time, but London follows close behind. As he traveled for Hearst as a reporter, a photo of him in the field often accompanied his published dispatches. His face appeared in ads for typewriters, grape juice, and cigarettes. He understood the power of an image and had an early interest in photography – and he regretted never having taken a picture in the Klondike, the locale usually associated with him. He developed many of his photographs.

In their introduction, the editors note, “The artistic and historical value of London’s photographs makes them an accomplished body or work. Of course, London was not primarily a photographer who had adventures but rather an adventurer and writer who made photographs. Yet he thought of himself as a professional: he expected to sell his photographic output just as he did his writing. His photographic work includes virtually no touristic photographs.”

In their introduction, the editors note, “The artistic and historical value of London’s photographs makes them an accomplished body or work. Of course, London was not primarily a photographer who had adventures but rather an adventurer and writer who made photographs. Yet he thought of himself as a professional: he expected to sell his photographic output just as he did his writing. His photographic work includes virtually no touristic photographs.”

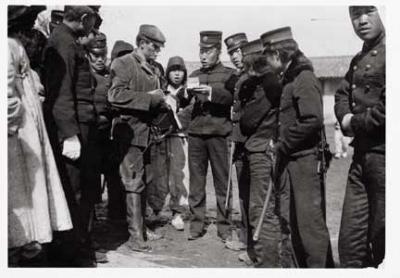

In 1904, Hearst sent London to cover the Russo-Japanese War. (The United States and Britain were supporting the Japanese with financial aid and diplomacy.) Taking photos of the Japanese, London was arrested several times but never ill treated. On one occasion after his camera was confiscated, Japanese photographers conspired to recover his equipment. London made his way to Korea where Japan’s forces had advanced. One night in Seoul, he gave a reading of The Call of the Wild to an audience of Japanese officers. Clearly, London was a global celebrity. Meanwhile, Hearst complained that London’s dispatches sounded more like short stories than hard news or descriptions of battles.

London’s photography is generously displayed in this large-format book – the images are large, cushioned in white space, and frequently supplemented with London’s commentary. The running narrative by the editors is both an appreciative critique of the photographs and a history of their significance to the culture of the time. But London himself was always a story – and he comes across as a living presence among his photography.

London’s photography is generously displayed in this large-format book – the images are large, cushioned in white space, and frequently supplemented with London’s commentary. The running narrative by the editors is both an appreciative critique of the photographs and a history of their significance to the culture of the time. But London himself was always a story – and he comes across as a living presence among his photography.

At 5:13 am on April 18, 1906, London and his wife were asleep in their Sonoma ranch when the earthquake struck San Francisco. Thirty minutes later, they were on their horses, riding to the train station at Santa Rosa. By the afternoon, they were in San Francisco and, as London wrote, “we spent the whole night in the path of the flames.”

“In his photographs as in his fiction,” the editors write, “London most often sought to capture the common emotional life of his subjects – not a culture, but the individuals who made it up. Even in his photographs of the many buildings destroyed by the San Francisco earthquake, his compositions evoke the human toll of the cataclysm, sometimes by contrasting the size of human subjects with the massive ruins around them … He was drawn to any subject that indicated something of the struggle to survive.”

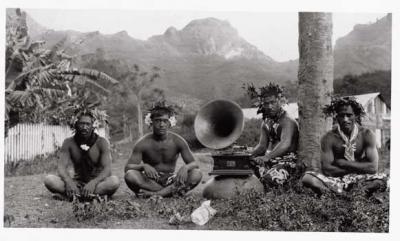

Jack London, Photographer is organized around his major travel projects – the earthquake section being the striking exception: London took very few photos of the places where he lived. The final three chapters follow his documentation of sailing trips to the Hawaiian Islands, the Marquesas, Solomon Islands, and Bora Bora. London presciently feared the demise of these cultures. His coverage of the Mexican Revolution in 1914 brought his final photos, and he died in 1916 at age 40.

Jack London, Photographer is organized around his major travel projects – the earthquake section being the striking exception: London took very few photos of the places where he lived. The final three chapters follow his documentation of sailing trips to the Hawaiian Islands, the Marquesas, Solomon Islands, and Bora Bora. London presciently feared the demise of these cultures. His coverage of the Mexican Revolution in 1914 brought his final photos, and he died in 1916 at age 40.

London called his photographs “human documents,” a phrase he picked up from Edmond Goncourt. This wonderful book, packed with London’s notes on the images he had taken so selectively, strongly communicates his unique humanity and his respect for people striving to live among battering biological and social forces.

[Published by the University of Georgia Press on September 15, 2010. 288 pages, 230 duotones. $49.95 hardcover.]