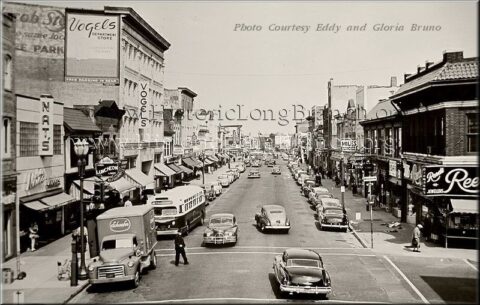

Robert Pinsky’s presence in Jersey Breaks summons up “The Hall,” a favorite poem from his collection Jersey Rain (2000) that begins, “The hero travels homeward and outward at once, / Master of circumference and slave to chance.” In his memoir, conjuring his youth in Long Branch, New Jersey, he names his primal conditions and selects the telling anecdotes that shape his self-mythology, while venturing outward and into the compulsion to make poetry out of an actual world. “The Hall” is a poem of archetypes that point to the coexistence of the metaphysical and the socio-political. It concludes, “Provincial, cosmopolitan, the hero embroiders, // Recollects, travels, and summons together all — / All manners of the dead and living, in the great Hall.” Pinsky emerged from the home provinces of the Jersey shore, and evolved into a cosmopolitan who continues to be stimulated by the difficulties inherent in his art of spectral embroidery.

The hero has no interest in picking himself apart. He is not haunted by his past – he is the haunter of it. There are no traumas or deprivations to relate, no dysfunctional relationships with parents, no finger pointing. Milford Pinsky was apparently a sensible father and diligent optician. Sylvia Pinsky, Robert’s mother, was spirited, outspoken, empathic, and sometimes unpredictable. “The difficult mother can become a cliché,” the son now concludes, thus deflating a considerable part of the memoir industry. As for the cliches of oneself, Pinsky won’t indulge in a tale of discovering one’s “true self.” Instead, we enjoy the vigorous voice of his preferred self:

The hero has no interest in picking himself apart. He is not haunted by his past – he is the haunter of it. There are no traumas or deprivations to relate, no dysfunctional relationships with parents, no finger pointing. Milford Pinsky was apparently a sensible father and diligent optician. Sylvia Pinsky, Robert’s mother, was spirited, outspoken, empathic, and sometimes unpredictable. “The difficult mother can become a cliché,” the son now concludes, thus deflating a considerable part of the memoir industry. As for the cliches of oneself, Pinsky won’t indulge in a tale of discovering one’s “true self.” Instead, we enjoy the vigorous voice of his preferred self:

“I am echoing a comic style, the inverted swagger of my parents and their friends. I was born into a little-known social class, a provincial, small-town, or neighborhood American gentility who have been in one place for a generation or two. We come from various religions and skin tones, we may have grandparents who are migrants or dirt farmers, but we are confident frogs in the little ponds we inherit or devise.”

Jersey Breaks is largely about insisting on having things your own way and getting away with it. Such was the example set by grandfather Dave Pinsky, Prohibition bootlegger, then bar proprietor. Young Robert was a mediocre student, or rather, he was an avid reader who spurned the orthodoxies of schooling. Music became his expressive refuge; he played the horn at school dances and later during ROTC drills at Rutgers where Paul Fussell became his first notable teacher. Before college, he read Lewis Carroll’s Alice, Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee, R. L. Stevenson, James Joyce, and Walter Scott. Then later, the first poetry – Ginsberg, Moore, Eliot, Yeats. He heard something similar in the work of Eliot and Ginsberg, though his instructors said otherwise.

In the essay “Responsibilities of the Poet” (1987), describing his sense of social responsibility, Pinsky wrote, “The feeling is not goodness, exactly, but rather the desire to think well of ourselves — the first civic virtue.” This melding of collective and personal worthiness (communal health and one’s best interests) is embedded in Pinsky’s perspective. But there is also contention and discord — with others and within oneself. One of the worst pieces of advice I ever received from a writing teacher was, “You need to affirm invention at the expense of argument.” Why not admit to both urges? Over the years, I’ve learned from and enjoyed Pinsky’s contentiousness. In the memoir, an episode concerning one Mr. Pulaski, a high school teacher who “took a terrific dislike to me” and whose rules young Robert openly contradicted, leads to speculation about poetic expression:

In the essay “Responsibilities of the Poet” (1987), describing his sense of social responsibility, Pinsky wrote, “The feeling is not goodness, exactly, but rather the desire to think well of ourselves — the first civic virtue.” This melding of collective and personal worthiness (communal health and one’s best interests) is embedded in Pinsky’s perspective. But there is also contention and discord — with others and within oneself. One of the worst pieces of advice I ever received from a writing teacher was, “You need to affirm invention at the expense of argument.” Why not admit to both urges? Over the years, I’ve learned from and enjoyed Pinsky’s contentiousness. In the memoir, an episode concerning one Mr. Pulaski, a high school teacher who “took a terrific dislike to me” and whose rules young Robert openly contradicted, leads to speculation about poetic expression:

“I have never matured completely beyond conflicts like that one between a hardworking, somewhat authoritarian coach and teacher on one side and an inwardly desperate, outwardly arrogant teenage saxophone player on the other. I still get into similar kerfuffles. A certain kind of A, sometimes, is not for me. Mr. Pulaski keeps appearing in new forms, and I keep taking the bait. Maybe, as they say about comedians, practicing a vocal art is rooted in aggression and need, reaching far back past adolescence into the plaintive, distressed, infantile origins of a human voice.”

Another teacher named Army Ippolito told his mother, “Your son doesn’t want to get an A” – and though she responds, “That’s okay, Army. Sooner or later, the cream always rises to the top,” her son reflects, “My secret grief was, I knew Army was right about me. Defying the sources of recognition, I needed to defeat myself and I couldn’t understand why.” Pinsky neither hyper-illuminates nor minimizes these traits – because the faults are necessary as well as indelible — and there will never be a consensus between the warring, internalized factions. The trick is in management. The poetry arises not despite conflicts and contradictions, but through them. So when Pinsky describes his experiences with an imposing teacher like Yvor Winters or the times spent at Robert Lowell’s famous office hours, he acknowledges their art and stature with unfeigned respect, and also goes looking for and assesses their deficits, as he does when taking inventory of himself.

“I am an expert at nothing except the sounds of sentences in the English language,” he says. We say silence is ineffable — but perhaps the ineffable is rarely silent. “I was blessed by growing up within a certain version of what can be called an ‘oral tradition,’” he writes. “I had the good luck to be raised among expert joke-tellers, complainers, arguers, schmoozers, boasters and liars.” Sound here is attitude, and certain attitudes are preferred. Sound is also the noise the mind makes when it leaps. So when it comes to poets, Pinsky’s partialities are distinct. For instance, speaking of Lowell’s work, he says, “In the personal narratives and declarations of Life Studies, many readers valued a directness that for me lacked an antic, disjunctive quality I prized in American life and poetry. Lowell’s autobiographical poems felt humorless and four-square. They were not enough like the movies of Mel Brooks or the eruptive comic strips of Walt Kelly.” As an adolescent, he discovered in Charlie Chaplin, Eartha Kitt and Cary Grant “an improvised, worldly quality I thought I recognized.”

There is plenty of the antic and disjunctive in Jersey Breaks. And much else. It is also a book of ethnicities, beginning with the Pinsky family’s Jewish identity (Dave Pinsky would have none of it). Springing up between the micro-stories are assertions about how we should regard ourselves as we read and write poems. For instance, “Ezra Pound says poetry is a centaur. That is, a thing of body and mind, in that order. If you are too cerebral to hear it, you miss the point. A busy compulsion to understand may be more common than its opposite, an unwillingness to think.” He is candid about his own postures, noting (with no regrets) that the title poem of his first book, “Sadness and Happiness,” is “social and antisocial … a true record of my deepest, most jumbled affiliations … a self-preoccupied rant against self-preoccupation.”

There is plenty of the antic and disjunctive in Jersey Breaks. And much else. It is also a book of ethnicities, beginning with the Pinsky family’s Jewish identity (Dave Pinsky would have none of it). Springing up between the micro-stories are assertions about how we should regard ourselves as we read and write poems. For instance, “Ezra Pound says poetry is a centaur. That is, a thing of body and mind, in that order. If you are too cerebral to hear it, you miss the point. A busy compulsion to understand may be more common than its opposite, an unwillingness to think.” He is candid about his own postures, noting (with no regrets) that the title poem of his first book, “Sadness and Happiness,” is “social and antisocial … a true record of my deepest, most jumbled affiliations … a self-preoccupied rant against self-preoccupation.”

Assuming that most of his anecdotes have been told before, I wondered at the outset about how Pinsky would go about gratifying his desire for the unexpected in his work. My hunch is that the narrative’s recursive form, its avoidance of the strictly chronological and the usual memoirist’s “arc,” allowed his materials to swirl, settling here and there in felicitous patterns of relation. Along the way, he briefly but adequately covers many personal highlights – his lively translation of Dante’s Inferno, the Favorite Poem Project taking shape through his terms as Poet Laureate, his friendships with poets, his travels.

In 2005, Pinsky went to North Korea and “learned a little about the Korean national hero and poet Manhae, the pen name of Han Yong-un (1879-1944).” In the Korean poet’s work, Pinsky recognized that “his poems make one idiomatic gesture of the erotic, the political and spiritual.” Combining these urges sonically, such a gesture gives the poet the potential not only to confront the evidence of “a nameless, densely crazy power that ruled the world,” but also to comprise an integrative vision that has not yet been fully realized in the public square. In his own poetry, Pinsky has achieved similar effects — and in Jersey Breaks, he tells his story by way of the sounds which have embodied it. Cesare Pavese wrote in his notebook, “The delight of art – perceiving that one’s own way of life can determine a method of expression.” I hear that delight throughout Jersey Breaks.

[Published by W.W. Norton on October 11, 2022, 236 pages, $26.95 US]

/ / /

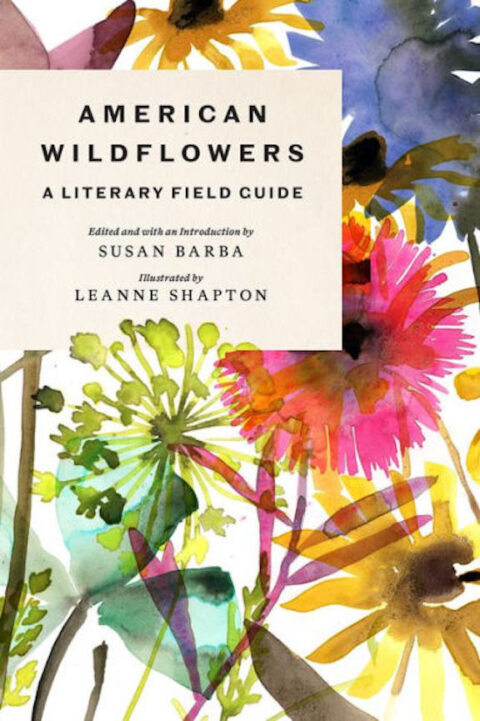

In one of his notebooks, Fernando Pessoa wrote, “Useless city gardens seem to me like birdcages in which the trees and flowers in all their colorful spontaneity only have space enough not to have space, a place they cannot leave, and a beauty of their own without the life that belongs to such beauty.” The untrammeled, blooming life he envisioned is celebrated in Susan Barba’s anthology American Wildflowers: A Literary Field Guide. “Even the most ephemeral wildflowers can assume outsize significance,” she writes in her introduction, “for they are symbols of survival and subversion, of the triumph of the small and meek, of the virtues of the weedy, ugly, and malodorous. Like the birds we rely on their regular return.”

Barba calls the collection “a florilegium, the Latin word for a gathering of flowers, just as anthology is Greek for a bouquet.” She also notes that the term “native plant” is replacing the word “wildflower” among those who take a custodial approach to these plants, concerned with the health of their habitats. But native plants include non-flowering ones, and Barba sees, or rather hears a reason to direct our attention to those that flower:

“The word wildflower has an aesthetic power that comes partly from the picture the word creates in the mind – that necessary quality of wildness – and partly from its sound. The long, sighing, stressed first syllable – why – the stress end-stopped by –ld, then relieved through the slower unfolding of flower, with its paired unstressed syllables: a singing word, of significance to poets, if not to scientists.”

[Ohi’a / Metrosideros polymorpha]

Like a field guide, the book’s table of contents highlights the common names of wildflower species, and the species are grouped into families. For instance, the selections begin with Sandra Lim’s poem “Snowdrops” (Snowdrop, Galanthus nivalis) and Yusef Komunyakaa’s “Narcissus” (Narcissus, Narcissus pseudonarcissus), organized under the family name Amaryllidaceae / Onion family. Ninety-seven additional poems follow in 31 families. The writers, a diverse cohort, represent three centuries of attention devoted to wildflowers – Emily Dickinson is here and Lydia Davis, Meriwether Lewis (“Wednesday June 11th, 1806”) and Cyrus Cassells. The genres of writing are various: “letters, reviews, bulletins, essays, excerpts from novels, reports from the field, and, most of all, poems.”

While writing these paragraphs, it occurred to me to go to my wife’s studio where she has hung a botanical illustration (circa 1840) by an S. Holden, depicting Dendrobium macrophyllum or Pastor’s Orchid, native to Indonesia. As Barba notes, the history of botanical illustration is important to scholarship – and to our understanding of colonization. In American Wildflowers, Leanne Shapton’s “incandescent” watercolors embody the essential leap from observation to imagination – making us aware of shape and color and texture, as well as a desire to let our spirits expand along with the wildflowers.

A few more of the pieces here – Ginsberg’s “Sunflower Sutra,” Stephanie Burt’s “Wildflower Meadow, Medawisla,” Denise Levertov’s “The Message,” Ross Gay’s “Ending the Estrangement.” There are contributions by Henry David Thoreau and Herman Melville, Wallace Stevens and Marianne Moore, Rita Dove, David Baker, Gary Snyder, Jorie Graham, Camille Dungy, Bernadette Mayer, Leslie Marmon Silko, Natalie Diaz, D. A. Powell and many more.

[Acony bell, Oconee bells / Shortia galacifolia]

In my springtime yard, we watch for the appearance of Johnny Jump-ups (Viola cornuta), Buttercups (Ranunculus bulbosus) and Liverwort (Hepatica nobilis). And also, Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale). There are Trillium in the woods, and we have cultivated Bloodroot. Emily Dickinson:

To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee,

One clover, and a bee,

And revery.

The revery alone will do,

If bees are few.

In American Wildflowers, the plants lead us into a vast and generous variety of experiences, contemplations and witnessing. And most of all, the freedom of revery and its flourishing among the freedom of wildflowers.

In American Wildflowers, the plants lead us into a vast and generous variety of experiences, contemplations and witnessing. And most of all, the freedom of revery and its flourishing among the freedom of wildflowers.

[Published by Abrams on November 5, 2022, 340 pages, $29.99 US hardcover]

0 comments on “on Jersey Breaks: Becoming an American Poet, a memoir by Robert Pinsky & American Wildflowers: A Literary Field Guide by Susan Barba”