“For me, the good photographer is not the guy who goes on the street for ten minutes and takes this fantastic picture,” Josef Koudelka told James Estrin of The New York Times in 2013. “The good photographer must create the conditions so that he can be good.” Creating conditions, Koudelka’s way of living as much as of making pictures, has been his lifelong habit. Yet the timely creation of a fantastic street picture assured both his career and exile from his home country.

Born in 1938 in Moravia, Koudelka came to Prague as a teen and was trained as an aeronautical engineer. His job required trips to nearby countries where he repaired small planes and crop-dusters. On the road, he took pictures — landscapes, but also his first photos of gypsies starting in 1962, twenty-seven of which formed the first exhibition of his work in a Prague theater lobby in 1967. Even then, he experimented with darkroom interventions like cropping, collage, focus, and grain.

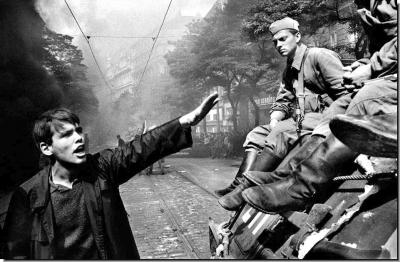

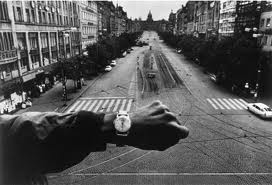

In August, 1968, he returned from Romania the day before Russian forces rolled into the city to crush the “Prague Spring.” Koudelka loaded his Exakta Varex (equipped with a 25mm Flektogon f4 lens) with East German 400 ASA movie film and went out into the streets to shoot the occupation, at times pursued and shot at by the Russians through the city squares. From August 21 to 27, he produced over 5,000 exposures. Yet until 2008, only 10 of those photographs had been published, most famously “Hand and Wristwatch” which documents the exact moment Soviet tanks rolled into the city.

In August, 1968, he returned from Romania the day before Russian forces rolled into the city to crush the “Prague Spring.” Koudelka loaded his Exakta Varex (equipped with a 25mm Flektogon f4 lens) with East German 400 ASA movie film and went out into the streets to shoot the occupation, at times pursued and shot at by the Russians through the city squares. From August 21 to 27, he produced over 5,000 exposures. Yet until 2008, only 10 of those photographs had been published, most famously “Hand and Wristwatch” which documents the exact moment Soviet tanks rolled into the city.

His invasion photos were smuggled out of Prague and appeared in Look and the Sunday Times Magazine (London). The Magnum Photos agency began its custodianship of his work. “Hand and Wristwatch” was attributed to “P.P.” — Prague Photographer. In 1970, Koudelka flew out of Prague to London on an 80-day exit visa; on the way to the airport, he told his father that he was the person who shot the instantly iconic photo. But it was not until 1984 that Koudelka publicly revealed his authorship.

His invasion photos were smuggled out of Prague and appeared in Look and the Sunday Times Magazine (London). The Magnum Photos agency began its custodianship of his work. “Hand and Wristwatch” was attributed to “P.P.” — Prague Photographer. In 1970, Koudelka flew out of Prague to London on an 80-day exit visa; on the way to the airport, he told his father that he was the person who shot the instantly iconic photo. But it was not until 1984 that Koudelka publicly revealed his authorship.

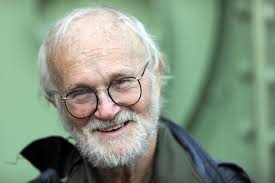

It is not that Koudelka has shunned exposure, publication or notoriety. It is quite simply that he has organized his life solely around taking photographs — and strictly on his own terms. His obsessive and eccentric habits of work and creativity, covered in five essays, comprise the heart of Josef Koudelka: Nationality Doubtful, published in conjunction with a forthcoming 2014-15 exhibition of the same title at The Art Institute of Chicago, The Getty Museum in Los Angeles, Fundacion MAPFRE of Madrid.

The Prague photos are renowned as photojournalism, but by 1970, the beginning of his nine-year exile in England, Koudelka had rejected the genre. “I don’t like picture stories,” he said, “in fact I think picture stories destroyed all photography. I am interested in one picture that tells many different stories to different people. This is to me the sign of a good picture.” In 1971, Koudelka met Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris. The two became close friends, even though Koudelka was openly critical of his colleague’s work. Cartier-Bresson, the great photojournalist, was exclusively interested in events, context, and people, and was known for his disinterest in photography as art. Although the two often debated, Cartier-Bresson was responsible for acquiring the two Leicas and the 35mm and 50mm lenses that Koudelka adopted in exile.

The Prague photos are renowned as photojournalism, but by 1970, the beginning of his nine-year exile in England, Koudelka had rejected the genre. “I don’t like picture stories,” he said, “in fact I think picture stories destroyed all photography. I am interested in one picture that tells many different stories to different people. This is to me the sign of a good picture.” In 1971, Koudelka met Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris. The two became close friends, even though Koudelka was openly critical of his colleague’s work. Cartier-Bresson, the great photojournalist, was exclusively interested in events, context, and people, and was known for his disinterest in photography as art. Although the two often debated, Cartier-Bresson was responsible for acquiring the two Leicas and the 35mm and 50mm lenses that Koudelka adopted in exile.

Koudelka’s first collection, Gypsies, published by Aperture in 1975, included photographs taken before his flight from Czechoslovakia. Visiting and staying at Roma festivals, religious events, horse fairs, and encampments throughout Europe was his lifelong preoccupation. When his first major American show was hung at MoMA, the title of one critic’s review must have pleased Koudelka: “Documentary Photos Without Captions Leave Us in the Dark.” In 1988, Exiles was published, also including some gypsy photos, but more generally concerned with strangeness, solitary figures, and stray animals. Koudelka recalled, “When I published my Gypsy book I felt like a prostitute because suddenly anyone who had money could buy it.”

During all these years, Koudelka would travel in the spring and summer and work in the darkroom all winter. He never paid rent in England or applied for British citizenship. As Amanda Maddox notes in her fine essay “A Stranger in No Place,” “The government categorized him as “Nationality Doubtful,” an official status given to those whose birthplace could not be verified and whose identity as British was uncertain.” On the road for weeks and months, the gregarious Koudelka felt as though he was “a foreigner everywhere but a stranger in no place.” In 1987, he became a French citizen — and could sometimes be found sleeping under a desk at the Magnum Photos office in Paris. Koudelka had a sister in Toronto but had no desire for family life. He had three children by three different women in three different countries.

During all these years, Koudelka would travel in the spring and summer and work in the darkroom all winter. He never paid rent in England or applied for British citizenship. As Amanda Maddox notes in her fine essay “A Stranger in No Place,” “The government categorized him as “Nationality Doubtful,” an official status given to those whose birthplace could not be verified and whose identity as British was uncertain.” On the road for weeks and months, the gregarious Koudelka felt as though he was “a foreigner everywhere but a stranger in no place.” In 1987, he became a French citizen — and could sometimes be found sleeping under a desk at the Magnum Photos office in Paris. Koudelka had a sister in Toronto but had no desire for family life. He had three children by three different women in three different countries.

Just when the figure of the gypsy seemed to become Koudelka’s signature psychic image, he departed from it. Since 1986, he has exclusively shot landscapes with a panoramic camera. Although there are no humans in his frames, he regards the landscape with the same temperament, eye, and emotion formerly trained on people. But this transition was not abrupt. Gilles Tiberghien points out that the landscapes in Exiles “are evocative of the exile’s point of view, and the men and women who appear in those landscapes seem to be looking for a sign, something that might give meaning to their lives.” Even the Prague photos captured the “tragic disarray” of a city under siege.

Just when the figure of the gypsy seemed to become Koudelka’s signature psychic image, he departed from it. Since 1986, he has exclusively shot landscapes with a panoramic camera. Although there are no humans in his frames, he regards the landscape with the same temperament, eye, and emotion formerly trained on people. But this transition was not abrupt. Gilles Tiberghien points out that the landscapes in Exiles “are evocative of the exile’s point of view, and the men and women who appear in those landscapes seem to be looking for a sign, something that might give meaning to their lives.” Even the Prague photos captured the “tragic disarray” of a city under siege.

What characterizes a Koudelka photograph? As one critic puts it, “the monumental.” Koudelka replaced the urge to narrative context with a capacity for weight.

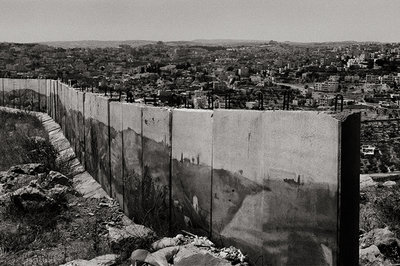

Koudelka shot his melancholy landscapes throughout Western Europe in the 1980s, including shots of ancient ruins. But in the mid-90’s, Koudelka was invited to participate in a group project, “This Place: Making Images, Breaking Images – Israel and the West Bank.” At first, Koudelka balked, unwilling to accept any strictures or political prerequisites. But he relented and joined eleven other shooters, and in 2003 he published Wall: Israeli and Palestinian Landscapes.

He remarked, “I grew up behind a wall so I knew what it was … When I showed my book in Israel, people told me it is not a political book … But an Israeli poet said to me, ‘You did something important — you made the invisible visible.’ He meant that Israelis don’t want to see that wall and they don’t even want to talk about it. They don’t go across it.”

He remarked, “I grew up behind a wall so I knew what it was … When I showed my book in Israel, people told me it is not a political book … But an Israeli poet said to me, ‘You did something important — you made the invisible visible.’ He meant that Israelis don’t want to see that wall and they don’t even want to talk about it. They don’t go across it.”

But when Koudelka focuses on the people-less landscape, he is not reaching for a one-sided political narrative. He wants us to consider the landscape as a presence in the drama. “We have a divided country and each group tries to defend themselves,” he said. “The one that can’t defend itself is the landscape … I am principally against destruction — and what’s going on is a crime against the landscape.”

In his introduction to Exile, Czeslaw Milosz dramatized the restlessness, turmoil, and necessity of Koudelka’s work. He wrote, “Exile is a test of internal freedom and that freedom is terrifying. Everything depends upon our own resources, of which we are mostly unaware and yet we make decisions assuming our strength will be sufficient. The risk is total, not assuaged by the warmth of a collectivity where the second rate is usually tolerated, regarded as useful and even honored. Now to win or to lose appears in a crude light, for we are alone and loneliness is a permanent affliction of exile.”

In his introduction to Exile, Czeslaw Milosz dramatized the restlessness, turmoil, and necessity of Koudelka’s work. He wrote, “Exile is a test of internal freedom and that freedom is terrifying. Everything depends upon our own resources, of which we are mostly unaware and yet we make decisions assuming our strength will be sufficient. The risk is total, not assuaged by the warmth of a collectivity where the second rate is usually tolerated, regarded as useful and even honored. Now to win or to lose appears in a crude light, for we are alone and loneliness is a permanent affliction of exile.”

But for the itinerant Koudelka, exile is a sort of a priori condition. It was apparent to him even when he lived in Prague and ventured to the countryside to photograph gypsies. “I never stay in one country more than three months,” he said. “Why? Because I was interested in seeing, and if I stay longer I become blind … I became what I am from how I was born, but also from what photography made from me. People ask me, ‘Are you still Czech or are you French?’ I am the product of this continuous traveling, but I know where I came from.”

[Published by Yale University Press on July 29, 2014. 224 pages, $50.00 oversize paperback. Includes 200 color and b/w plates.]