The clairvoyant I’ve visited occasionally for the past 20 years once told me that each of us runs into a recurring challenge — a social circumstance, uncomfortably familiar, that usually leads to trouble. He described my particular dilemma, which had never occurred to me as a repetitive scene, but once pointed out now seemed to have a circular shape and theme. He then mentioned his own inescapable fix which, he claimed, is triggered by his appearance — body type, skin color, way of moving, tone of voice, and outward-flung energy all combining to create disturbance in specific settings, especially bars. His larger message, I suppose, is that we attract our antagonists. The anecdotes proving his theory were entertaining and convincing. They clarified and added form to what he sensed as a thematic arc of his life. My recurring challenge? That’s my business. I’m not a memoirist.

I approached Sven Birkerts’ The Art of Time in Memoir with a mistrust of the genre’s latest output – its calculated muted epiphanies, its obligatory tamping down of knowingness which still shows through, the elevating of any object to a monument and any person to Man or Woman of the Year. “But we cannot allow the many to wreck things for the few,” declares Birkerts. He adds, “One of the distinguishing features of the dull and dutiful memoirs that crowd our display tables is that they measure all experience in terms of a standardized, or universalized scale of value.” The Art of Time in Memoir unfolds as a clear and useful lecture on effective technique as illustrated in exemplary memoirs. “Apart from whatever painful or disturbing events they recount, their deeper ulterior purpose is to discover the nonsequential connections that allow those experiences to make larger sense; they are about circumstance becoming meaningful when seen from a certain remove.” But this, of course, has always been true of most memoirs, though one could name several that have no interest in dealing with nonsequential maneuvers. In fact, one of the reasons that there are so many mediocre memoirs on the display tables is that playing with the nonsequential often makes way for the non-essential, the uninteresting.

I approached Sven Birkerts’ The Art of Time in Memoir with a mistrust of the genre’s latest output – its calculated muted epiphanies, its obligatory tamping down of knowingness which still shows through, the elevating of any object to a monument and any person to Man or Woman of the Year. “But we cannot allow the many to wreck things for the few,” declares Birkerts. He adds, “One of the distinguishing features of the dull and dutiful memoirs that crowd our display tables is that they measure all experience in terms of a standardized, or universalized scale of value.” The Art of Time in Memoir unfolds as a clear and useful lecture on effective technique as illustrated in exemplary memoirs. “Apart from whatever painful or disturbing events they recount, their deeper ulterior purpose is to discover the nonsequential connections that allow those experiences to make larger sense; they are about circumstance becoming meaningful when seen from a certain remove.” But this, of course, has always been true of most memoirs, though one could name several that have no interest in dealing with nonsequential maneuvers. In fact, one of the reasons that there are so many mediocre memoirs on the display tables is that playing with the nonsequential often makes way for the non-essential, the uninteresting.

In corporations, continuing education is ministered by highly paid, tightly scripted consultants who instruct that “a toleration for ambiguity” is a management asset. So, I think of the recently swelling ranks of memoirists, churning out recollections of how they learned to accept life’s ambiguities, disappointments, bewilderments, and inconclusiveness. So much pleasant expansion of consciousness, but so meager a contribution to our GNP. “Only in the last quarter century or so,” says Birkerts, has the memoir “refurbished itself in an expressively contemporary way.” But expressiveness itself has been commoditized and processed in many memoirs – just as it has in much poetry.

Has the literary memoir commandeered the vehicle once called the “familiar essay”? “Today’s readers encounter plenty of critical essays (more brain than heart) and plenty of personal – very personal – essays (more heart than brain, but not many familiar essays (equal measures of both),” writes Anne Fadiman in the introduction to her new book of familiars, At Large and At Small. “I believe the survival of the familiar essay is worth fighting for … an expression of my own character, a blend of narcissism and curiosity.” The personal essays of Floyd Skloot, collected in In the Shadow of Memory and A World of Light, exemplify the brainy and self-attuned narrative stance she favors. Skloot’s work follows the venerable path of the classic essay. Reading his emotionally taut pieces on illness or the damaging whims of his mother, one never registers his work as “refurbished in an expressively contemporary way.” His memoirs are expressed in the tested old ways of sounding new.

I’m a fan of mass market memoirs, especially those recalling debauchery, treachery, and crime. One of my favorites is The Godson: A True-Life Account of 20 Years Inside the Mob, by Willie Fopiano (as told to John Harney, St. Martin’s Press, 1993). How sad to witness the adulteration of this pure form by literary and academic types. Some will say that Willie Fopiano dictated an autobiography, not a memoir, because in the latter “the search for patterns and connections is the real point – and glory – of the genre,” as Birkerts suggests. But patterns and connections, not to mention a unique narrative voice, mark Art Pepper’s great unliterary autobiography, Straight Life. No matter, Birkerts says that in contrast to autobiography, memoir presents “not the line of the life but the life remembered … presentation of life as it is naturally reconstituted by memory.” For some writers, memoir may now offer a grab for a measure of pop-style selfhood – but please, with modesty and taste!

The Art of Time in Memoir joins Patricia Hampl’s I Could Tell You Stories (Norton, 1999) as among the most insightful books on the genre, each helping us establish standards for excellence. Birkerts acknowledges the growing compost of memoir, but asks us not to disparage the genre nor disregard its accomplished power. Hampl confronts the most pointed objections to memoir: “But why write memoir? Why not call it fiction and be done with it? My answer, naturally, is a memoirist’s answer. Memoir must be written because each of us must possess a created version of the past. Created: that is, real in the sense of tangible, made of the stuff of a life lived in place and in history. And the downside of any created thing as well: We must live with a version that attaches us to our limitations, to the inevitable subjectivity of our points of view. We must acquiesce to our experience and our gift to transform experience into meaning.” This explanation seems to invalidate the assumption that more and more memoirs are being written because our culture is squelching selfhood; one writes by embracing a postmodern provisional self and pursuing the satisfaction in creating tentative meaning around it. Perhaps Birkerts disagrees when he insists, “Increasingly enslaved by our electronic extensions – our tools and conveniences – we have a harder time living the kinds of lives that can be given contour and written about,” thus increasing the premium for memoirs. But writers are using their PCs to produce more memoirs than ever, eagerly awaiting that email or cell-call from their agents. If a life is lived in blandness, technology isn’t to blame – but surely, there must be a memoir-in-process discovering its grand theme in the ruination of a life by encroaching digital communications.

The Art of Time in Memoir joins Patricia Hampl’s I Could Tell You Stories (Norton, 1999) as among the most insightful books on the genre, each helping us establish standards for excellence. Birkerts acknowledges the growing compost of memoir, but asks us not to disparage the genre nor disregard its accomplished power. Hampl confronts the most pointed objections to memoir: “But why write memoir? Why not call it fiction and be done with it? My answer, naturally, is a memoirist’s answer. Memoir must be written because each of us must possess a created version of the past. Created: that is, real in the sense of tangible, made of the stuff of a life lived in place and in history. And the downside of any created thing as well: We must live with a version that attaches us to our limitations, to the inevitable subjectivity of our points of view. We must acquiesce to our experience and our gift to transform experience into meaning.” This explanation seems to invalidate the assumption that more and more memoirs are being written because our culture is squelching selfhood; one writes by embracing a postmodern provisional self and pursuing the satisfaction in creating tentative meaning around it. Perhaps Birkerts disagrees when he insists, “Increasingly enslaved by our electronic extensions – our tools and conveniences – we have a harder time living the kinds of lives that can be given contour and written about,” thus increasing the premium for memoirs. But writers are using their PCs to produce more memoirs than ever, eagerly awaiting that email or cell-call from their agents. If a life is lived in blandness, technology isn’t to blame – but surely, there must be a memoir-in-process discovering its grand theme in the ruination of a life by encroaching digital communications.

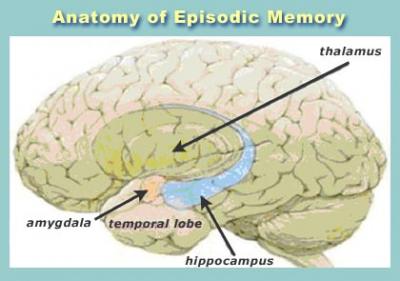

“The self-absorption that seems to be the impetus and embarrassment of autobiography turns into (or perhaps always was) a hunger for the world,” Hampl says. “Actually, it begins as hunger for a world, one gone or lost, effaced by time or a more sudden brutality.” “Hunger,” then, is what purifies the motives of the memoirist for Hampl. But this vindication, taken for granted across the genre, may create new embarrassments and mediocrities, and often does. Hampl also manages to yoke our fondest beliefs about memory to the mission of memoir: “Memory’s fundamental instinct is to formulate. That is, to make a past which is not only accurate (that would be a hopeless task, a naïve and misguided enterprise) but imaginatively accurate, as a work of art is.” Such a statement avidly greases the rails for memory’s enterprising glide into memoir, from shards of imagery to a work of art.

Birkerts adds to Hampl’s line of thought while preparing to stake out his own proving ground. Naming titles by Geoffrey Wolff, Tobias Wolff, Frank Conroy, Mary Karr, Annie Dillard, Rick Moody, Maureen Howard and others, he says, “Each account in some way proposes the idea that a life can be figured on the page as a destiny, a filling out of a meaningful design by circumstance, and that this happens once events and situations are understood not just in themselves but as states en route to decisive self-recognition.” Nabakov had said more or less the same thing in his memoir Speak, Memory, which Birkerts quotes: “The following of such thematic designs through one’s life should be, I think, the true purpose of autobiography.” Such themes manage to etch themselves without coercion into a writer’s fiction or poetry or plays, but memoir apparently requires their more deliberate pursuit. “Dramatizing the process of realization,” he says, “is the real point.” This is why Hampl can ask rhetorically, “Why not call it fiction and be done with it?” The refurbished “lyrical memoirist,” like the producer of the TV commercial for a pick-up truck that can pull a freight train, is comfortable with the disclaimer, “a dramatization.” Birkerts continues, “A memoir is, whatever its pretenses to the contrary, a narrative conceit; it creates a structure that is the life shaped and disciplined to serve the pattern, the hindsight recognition that is deemed to be the larger, more important truth.”

Birkerts adds to Hampl’s line of thought while preparing to stake out his own proving ground. Naming titles by Geoffrey Wolff, Tobias Wolff, Frank Conroy, Mary Karr, Annie Dillard, Rick Moody, Maureen Howard and others, he says, “Each account in some way proposes the idea that a life can be figured on the page as a destiny, a filling out of a meaningful design by circumstance, and that this happens once events and situations are understood not just in themselves but as states en route to decisive self-recognition.” Nabakov had said more or less the same thing in his memoir Speak, Memory, which Birkerts quotes: “The following of such thematic designs through one’s life should be, I think, the true purpose of autobiography.” Such themes manage to etch themselves without coercion into a writer’s fiction or poetry or plays, but memoir apparently requires their more deliberate pursuit. “Dramatizing the process of realization,” he says, “is the real point.” This is why Hampl can ask rhetorically, “Why not call it fiction and be done with it?” The refurbished “lyrical memoirist,” like the producer of the TV commercial for a pick-up truck that can pull a freight train, is comfortable with the disclaimer, “a dramatization.” Birkerts continues, “A memoir is, whatever its pretenses to the contrary, a narrative conceit; it creates a structure that is the life shaped and disciplined to serve the pattern, the hindsight recognition that is deemed to be the larger, more important truth.”

Birkerts moves from motive to mechanics, discussing the craft in light of “the core impulse of the genre,” the coming-of-age experience, the family-based memoir, and the trauma narrative. As for motive, he says “the memoirist writes, above all else, to redeem experience, to reawaken the past, and to find its pattern; better yet, he writes to discover behind bygone events a dramatic explanatory narrative.” But why do we like to read memoir? The answer may lie somewhere in André Aciman’s comment on reading Proust, quoted by Birkerts: “The seductive power of a novel such as the Search lies in its personal invitation to each one of us to read Marcel’s life as if we, and not Marcel, were its true subject.” As we know, seductive power includes and transcends technique. But by paying attention to Birkerts, the would-be memoirist will increase the odds of engaging our interest.

“The specificity of remembered details exposes the universal dynamics of memory,” Birkerts writes. “Specificity allows the scenes to come alive, and as they come alive they inevitably activate certain archetypes.” When memoir works, the reader’s memory is celebrated as well. “Memoir is undertaken not just as another kind of artistic expression, which is to say a work created for an intended audience, but also as an act of self-completion,” he says. But the memoirist’s self-completion is of no concern to the reader, who simply wants to be entertained, moved, and implicated on the slant. Sven Birkerts succeeded in this regard in his own memoir, My Sky Blue Trades. So did Willie Fopiano. A story well told is, as ever, a rare thing.

[Published January 2008 by Graywolf Press, 192 pages, $12.00, paperback. Also now available in The Art Of series: The Art of the Poetic Line by James Longenbach, The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot by Charles Baxter, and The Art of Attention: A Poet’s Eye by Donald Revell.]

The Art of Time in Memoir

While I don’t read much memoir, I’ve been thinking about ordering Birkerts’ book and am therefore grateful for your review.

Clairvoyant? How interesting … and unexpected!

After the fact

Now consider the memoirist’s limiting case: a life limpidly led, its pattern resolving instantly, its ellipses completed, the inception foretelling the denouement. Faced with such irrepressible biographical clarity, what then would remain for the memoirist to do? The likely answer: write a memoir, one retrofit with sufficient invention to properly deform the recollection. In short, a hyper-corrected life. We are a tale-telling species.