In 2000, The Institute of Economic Affairs, a British think tank of free-marketeers, published “The Representation of Business in English Literature,” a paper covering literature from the eighteenth century to the present. The final chapter by Dr. John Morris, subtitled “An Unprecedented Moral Quagmire,” begins, “It is difficult to find positive and appreciative images of business in 20th-century English literature.” By clinching the widespread theme of individual and cultural debasement by business, Morris’ nuanced catalog also proves the pervasiveness of business itself as subject matter. Yet we often think of business as material neglected by novelists and poets. Most writers I know who make at least some of their living in business don’t care about the lack of “appreciative images,” but often wonder at other writers’ lack of interest in or disparagement of business lives and materials.

There is literature about business and literature about work. Joshua Ferris, whose novel Then We Came to the End deals with office life, says in The Guardian, “Way-of-life work catches in its net most of literature’s biggest fish, in part because it offers the most heroic, or romantic, or tragic, or comic possibilities… Work puts Ishmael on the Pequod. Work brings Esther to Bleak House and sends Humbert Humbert to the house on Lawn Street.” Captain Marlowe, as job applicant, applies for a ship to sail and will be paid for the passage. Work is a common engine of fiction, but our interest in characters usually far exceeds their identity as workers. Bartleby prefers not to do any work, transfixing us by the blank remainder of his person. Bernardo Soares, in Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, works vaguely in some office, approaching Bartleby’s torpor. Hanta the shredder of books in Bohumil Hrabel’s little masterpiece Too Loud a Solitude seems to absorb all of Eastern Europe’s sad repression into his strangely comic mind.

Literature more specifically about business is harder to find. In a March, 2000 Fortune magazine essay, ” ’Sister Carrie’ Is Gone For Good,” James Wood notes literature’s brief emphasis on business between 1880 and 1930, and maintains that “today’s novelists have exchanged the spur of hostility for the saddle of indifferent disdain.” The main obstacle to effective use of business situations in fiction is the nature of work itself, according to Wood. “Work has become at once boringly familiar and strangely obscure, at once universal and closed,” he says. The novelist backs away from having to explain the details of the obscure routine, even though the job itself is widely practiced. “Contemporary work is too universal and too particular at the same time.” He also believes that our alienation from “means of production” has turned us unto “ghosts, and the connections we have to making things are spectral.” Characters have traditionally required a recognized status of some sort to ground them. King Lear is a ripping good story about royals. In A Thousand Acres, the characters have “means of production” status as farmers and act out the same tale, more or less. Is Wood saying corporate managers have no clear status, no ground for archetypal drama? Organizations aren’t set up to regard people as individuals, and this leads to deception, betrayal, looking after one’s own best interests, withholding information – conditions ripe for tension, but not necessarily for the development of alluring, spectral characters and minds.

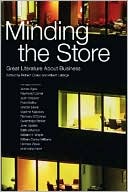

Harvard Business School asked Robert Coles to teach ethics to its fledging corporate managers, and his method employed literature to illuminate “the ironies agonies, ethical challenges, misunderstandings, and moments of grace in the world of commerce.” In Minding the Store, he and Albert LaFarge collect twenty-four short stories and novel excerpts that represent the moral ambiguities and dilemmas of doing business. For instance, Raymond Carver’s gem, “Are These Actual Miles,” centers on the protocols of buying and selling, starting with the first accelerating sentence: “Fact is the car needs to be sold in a hurry, and Leo sends Toni out to do it.” This story is part of the book’s first section on “selling in action.” Part 2, “The Office,” includes Franz Kafka’s “My Neighbor” in which the “wretchedly thin walls” between offices become a permeable membrane for a bizarre, imagined relationship. Part 3, “The Rich Man’s House,” fixated on the moral issues faced by the new monied middle class, includes John Cheever’s “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill” in which a businessman steals his neighbor’s wallet. Failure is the main topic of the fourth part, “Coming Up Short,” with stories by James Agee, Flannery O’Connor, and Studs Terkel among others. The final section, “You Can’t Take It With You,” reminds us of how often business and death are intertwined in fiction with Conrad’s “An Outpost of Progress,” Updike’s “My Uncle’s Death,” and the obligatory scene from Death of a Salesman.

Harvard Business School asked Robert Coles to teach ethics to its fledging corporate managers, and his method employed literature to illuminate “the ironies agonies, ethical challenges, misunderstandings, and moments of grace in the world of commerce.” In Minding the Store, he and Albert LaFarge collect twenty-four short stories and novel excerpts that represent the moral ambiguities and dilemmas of doing business. For instance, Raymond Carver’s gem, “Are These Actual Miles,” centers on the protocols of buying and selling, starting with the first accelerating sentence: “Fact is the car needs to be sold in a hurry, and Leo sends Toni out to do it.” This story is part of the book’s first section on “selling in action.” Part 2, “The Office,” includes Franz Kafka’s “My Neighbor” in which the “wretchedly thin walls” between offices become a permeable membrane for a bizarre, imagined relationship. Part 3, “The Rich Man’s House,” fixated on the moral issues faced by the new monied middle class, includes John Cheever’s “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill” in which a businessman steals his neighbor’s wallet. Failure is the main topic of the fourth part, “Coming Up Short,” with stories by James Agee, Flannery O’Connor, and Studs Terkel among others. The final section, “You Can’t Take It With You,” reminds us of how often business and death are intertwined in fiction with Conrad’s “An Outpost of Progress,” Updike’s “My Uncle’s Death,” and the obligatory scene from Death of a Salesman.

In his Essays in Persuasion (1933), John Maynard Keynes wrote, “Regarded as a means, the businessman is tolerable; regarded as an end, he is not so satisfactory.” Professor Coles’ Harvard MBAs are not bred to think of themselves as unsatisfactory, but novelists and poets have long perceived an Everyman quality in the businessman whose public actions draw out his private flaws. “Take care to sell your horse before he dies. The art of life is passing losses on,” wrote Robert Frost in “The Ingenuities of Debt.” One can easily imagine that Robert Coles succeeded in generating class discussion over pieces by Joseph Heller, Ann Beattie, and John O’Hara. But Minding The Store also shows once again that business somehow fails in the foreground, or rather that writers know instinctively to back away from the voracious, ritualistic center of business, not to let business become its own main character, enlisting or entrapping characters for its own purposes as in advertising. The repetitive routines of business and the standardization of its language – even with its goal-oriented Powerpoint pitches — suggest the futility of all enterprise, Ecclesiastes-like. All is vain. We go to work to forestall the inevitable moment when the business will fail or be acquired by strangers with other plans for us. Minding the Store reminds readers and writers of how variously well business sets off the tragic and the heroic, anxiety and insight.

[Click here to listen to Professor Coles on NPR’s Marketplace, which aired on July 31.]

[Published by The New Press on August 12, 2008, 320 pp., $25.95, hardcover]

Fictional business

Thanks for this review and for the link to the James Wood piece, since he’s one of my ‘always-read’ critics. The issue is one of concern to me, since I’m so very unfamiliar with business yet feel it is a must in fiction. Nothing pervades our lives in consumer society more thoroughly, except maybe sex.

http://lowebrow.blogspot.com