I should begin this review by reminding you that, in 2020, the citizens of Belarus rose up in mass protest against the dictator, Aleksander Lukashenko, who has ruled the country for nearly 30 years. I should remind you that he rigged a democratic election to extend his grip over the country, that he jailed his political opponents or forced them into exile, and that, when his own people responded with outrage and disgust, his police tortured and murdered peaceful protestors. It would be the responsible thing to do, to offer context, background. The presumption — fair or not — would be that you need such context; that there’s a good chance that you, whoever you are, have forgotten about the stolen election, the protests, the brutality of Lukashenko’s crackdown.

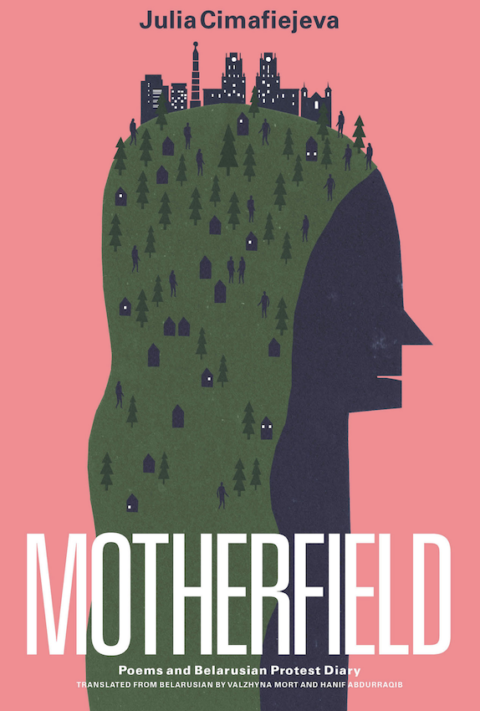

The Belarusian poet Julia Cimafiejeva’s new book Motherfield might be understood as an urgent call to remember, to resist the pull of amnesia, to celebrate the bravery of those who defied the regime — and to decry the obscenity of the regime itself. Motherfield — Cimafiejeva’s first book to appear in English — begins with excerpts from a “Belarusian Protest Diary,” which Cimafiejeva kept contemporaneously with the uprising against Lukashenko. (Her diaries were originally published in the Financial Times). The diaries are vivid and urgent. For those who, like me, followed the protests from a distance, they convey the intimate, lived experience of being on the streets in Minsk as the uprising unfolded. Many of the most powerful moments are also the most mundane. Cimafiejeva’s embodied, direct, reporting on the protests, has the capacity to fill ordinary objects and actions with violence, terror, and possibility. I am haunted, for instance, by a moment in October 2020 when Cimafiejeva and her husband take refuge from the police in a grocery store. Sopping wet from the rain, they try to blend in with the other shoppers, filling their basket with wine and food for dinner: “… we go to the cashier. I have my backpack on, and we usually try to be ecological, refusing the plastic bag, but not this time. This time we need an alibi.” As they head out into the street, the only shield they have is a plastic shopping bag.

The Belarusian poet Julia Cimafiejeva’s new book Motherfield might be understood as an urgent call to remember, to resist the pull of amnesia, to celebrate the bravery of those who defied the regime — and to decry the obscenity of the regime itself. Motherfield — Cimafiejeva’s first book to appear in English — begins with excerpts from a “Belarusian Protest Diary,” which Cimafiejeva kept contemporaneously with the uprising against Lukashenko. (Her diaries were originally published in the Financial Times). The diaries are vivid and urgent. For those who, like me, followed the protests from a distance, they convey the intimate, lived experience of being on the streets in Minsk as the uprising unfolded. Many of the most powerful moments are also the most mundane. Cimafiejeva’s embodied, direct, reporting on the protests, has the capacity to fill ordinary objects and actions with violence, terror, and possibility. I am haunted, for instance, by a moment in October 2020 when Cimafiejeva and her husband take refuge from the police in a grocery store. Sopping wet from the rain, they try to blend in with the other shoppers, filling their basket with wine and food for dinner: “… we go to the cashier. I have my backpack on, and we usually try to be ecological, refusing the plastic bag, but not this time. This time we need an alibi.” As they head out into the street, the only shield they have is a plastic shopping bag.

To negotiate the protests, to survive the police crackdown, Cimafiejeva and her husband must relearn to move through urban space: where to run, where to hide; where it is safe to gather. “You can easily be caught by policemen on your way to the rally or after it, when the protest body is weak. But inside of it, the masked men won’t touch us,” she observes. In its sheer human mass, the protest becomes a bubble of safety; the police wait in courtyards and vans to catch the isolated, the stragglers. Even symbols of safety and succor become corrupt, suspect. At a protest in October, she notices an ambulance off parked behind some trees — and it sends a shiver of fear through her: “Ambulance cars are often used by the police to stay unnoticed. We should always pay attention to the driver: if her wears a black balaclava, the ‘doctors’ inside are not going to relieve your pain but inflict it.”

Cimafiejeva and her husband thus become — have to become — acute interpreters of the apparently insignificant. On the second day of the protests, they pause in the street to debate whether a “range of round brown stains on the pavement” are blood or not. “They do look like dried drops,” she concludes, “I take photos of the stains, I want them to be kept, to be remembered.” The moment of doubt is characteristic of Cimafiejeva’s experience of the protests, as is her instinct to preserve, to make a record. With the internet shut off across the country, she reads news of the protest on Telegram, through proxy servers, absorbing other peoples’ records of the unfolding protests: “…the connection is nasty. Dozens of pictures and videos are loading slowly and, once loaded are horrible to see.” She scans the news to get updates on events that are happening outside her window, across the street. She gossips with friends about the possibility of martial law; her friends call with news of mass arrests. Cimafiejeva is simultaneously participant, witness, and observer.

The protests thus become both a lived experience and a literary experience. There is something apt about that: throughout Motherfield, the aesthetic constitutes one of the sites of Lukashenko’s power — and of the protestor’s resistance to his regime. The protestors and the regime are locked in a struggle over what it means to be Belarusian, and on what terms Belarus itself will be represented. On the day of the election, for instance, Cimafiejeva notes with grim humor the “cheap and vulgar aesthetics of [Lukashenko’s] power.” The entrance to her polling place is slathered in “red, white, and green balloon garlands,” the colors of the regime; in a beer tent just outside the school, a “teenage girl in a pseudo-folk costume with a wreath on her head is signing about her love for the Motherland,” which she celebrates in narrow, stereotypical terms: “Her Russian song checks off the golden wheat fields, the big blue lakes, and the slender white storks flying over our heads.”

Likewise, the protestors turn to the aesthetic, using songs, poems, and images as political weapons. Cimafiejeva observes, “When they take away your voice, use your voice. This is the main instrument of our protest … A poem read aloud and a song sung in the public space become the weapons of the revolution.” She documents guerilla performances — a choir that appears in public spaces like shopping malls and subway stations to sing “folk songs and old patriotic tunes to show their opposition to the government’s violence”; a group of artists who assemble in front of an exhibit celebrating “The Art of The Regime” with “photos of people tortured in the detention centers. Faces caked with blood, blue and red bruises on legs and arms, plastered limbs, bandaged heads, swollen eyes full of terror.” These brutalized bodies are, the protest suggests, the regime’s true aesthetic productions — not its patriotic songs or its red and green balloons.

Among these performances of aesthetic dissidence, one must count Cimafiejeva’s own work. This is true in a direct sense: she is often at these rallies and happenings, reading her own poetry. It is also true in an extended sense: one might read Motherfield as an attempt to contest the regime’s aesthetics. On August 12th, with the internet briefly back on, Cimafiejeva scrolls through her Facebook and encounters a collective cry of anguish — and a collective effort to document the brutality of the regime:

“… while reading the Facebook posts of my friends … I feel like I’m reading a book that might be written by Ales Adamovič or Sviatlana Alexievič. The same polyphonic choir that made me cry as a teenager over the book Out of the Fire (I also cried while reading Voices from Chernobyl and it was sobbing that prevented me from finishing Secondhand Time). Maybe later some author will compile all these painful posts and commentaries into one book, a document of the time that will tell what we have felt these days.”

Motherfield is not quite this choral, polyphonic record of collective trauma; it presents one voice, one experience. But the book does offer a challenge to official constructions of Belarusian literary history. The book opens with Cimafiejeva, “Waiting for you … in Yanka Kupala Park,” where, she “open[s her] notebook and starts musing.” The “you” is her husband, of course, but the reader doesn’t know that yet. Instead, this opening sentence of her diary serves as an invitation to the reader — who also might be the “you” Cimafiejeva is addressing — to join her in the park and to start musing with her. Once her husband does join her, they “cross Yakub Kolas square.” These are real places in Minsk. But they are also literary landmarks: though they are largely unknown in the West, Kupala (1882-1942) and Kolas (1882-1956) are central figures in the official history of Belarusian literature.[i] Cimafiejeva thus opens the book by situating herself in the center of Belarusian literary tradition — marking the way that such literary landmarks shape the experience of the capitol itself. But she does not move respectfully, piously, through these literary or physical spaces. She and her husband are headed to a protest; as they do so, she “spit[s] in disgust” at the police officers who monitor the park. When she “open[s her] notebook, and start[s] musing,” she is thus opening an alternate Belarusian canon, a literary tradition capable of speaking to the anxieties and agonies of living in Lukashenko’s Belarus.

Motherfield does not present itself as the triumphant realization of that project. If anything, it laments the limitations of what literature can accomplish in the face of state violence. At a literary festival in Minsk in October 2020, Cimafiejeva and her husband watch “the police beat and detain [students] in the street, just behind the windows where the bookfair guests can see.” Later, the same day, Cimafiejeva breaks down: “all the guilt, lack of readership, and despair become so unbearable on my shoulders that…I start weeping …” Likewise, after Cimafiejeva and her husband flee Belarus for a residency in Austria, she reports, “all I could feel was guilt. Guilt for being free. Guilt for being safe … Even now, after four months of life abroad, I have dreams about running and hiding from the police. Sometimes I manage to escape them while dreaming. Sometimes I have to wake up in order to escape.” The police — and, behind them, Lukashenko — have colonized the imagination itself; even in dreams, Cimafiejeva remains pursued, threatened, without even a plastic bag to shield her.

As her diary closes, then, Cimafiejeva leaves her readers wondering what freedom — literary and political — will require. In the second half of the book, Cimafiejeva moves into verse, with a series of lyric poems that recapitulate and extend the themes of the protest diaries. In these poems, Cimafiejeva does not exactly answer the question about freedom her diaries, implicitly, pose. Rather, she might be said to expand what that question means, and to insist on its depth and persistence. In the first poem in the sequence, “The Stone of Fear,” for instance, Cimafiejeva returns to fear, one of the predominate emotions of her protest diary, writing, “I have been handed down a trust fund / of fear— / a family heirloom, passed / generation to generation …” The immediate fear of confronting police in the street expands, becomes a generational burden, a legacy. Likewise, the immediate imagery of the protest diary — with its parks and squares, police vans and grocery stores — is, as it were, transposed into another key, a surreal, imagistic register. “In the Garden of Great-Grandmothers” translates the garland of balloons decorating her polling place into a metaphor for Cimafiejeva’s own literary productions:

I farm.

But in my field grow only

red grass,

green grief

The police pursue her in her dreams; likewise, the state colonizes her poetry, reducing its crop to the same sterile, patriotic colors — and the guilt and shame that come with it. As she writes, later, in “Body of a Poetess: “A poet’s body belongs to his motherland. / Motherland speaks through the poet’s mouth.” But the poems do not remain stuck in this constrained condition. Even as they document the intransigence of the Lukashenko regime, the way it reaches into and colonizes the psyche of the poet, they also often proclaim their own freedom, insistently so. “Body of a Poetess” ends with such a proclamation: “No, you don’t need the body of the poetess. / It’s mine.”

At the risk of over-reading Cimafiejeva’s literary practices, I would suggest that the language of her poems constitutes one such gesture of resistance, one such assertion of freedom. The poems are written in Belarusian and appear in the original in this bilingual edition, alongside English translations by Valzhyna Mort and Hanif Abdurraqib. Encountering the Belarusian language, immediately after Cimafiejeva’s protest diaries, is a bracing and powerful gesture: one thinks of the teenage girl at Cimafiejeva’s polling place singing her patriotic song in Russian. There are no “golden wheat fields … big blue lakes … [or] slender white storks” in these poems. Instead, one encounters the Belarusian language put to the task of conveying a Belarusian experience of political and ecological catastrophe.

At the risk of over-reading Cimafiejeva’s literary practices, I would suggest that the language of her poems constitutes one such gesture of resistance, one such assertion of freedom. The poems are written in Belarusian and appear in the original in this bilingual edition, alongside English translations by Valzhyna Mort and Hanif Abdurraqib. Encountering the Belarusian language, immediately after Cimafiejeva’s protest diaries, is a bracing and powerful gesture: one thinks of the teenage girl at Cimafiejeva’s polling place singing her patriotic song in Russian. There are no “golden wheat fields … big blue lakes … [or] slender white storks” in these poems. Instead, one encounters the Belarusian language put to the task of conveying a Belarusian experience of political and ecological catastrophe.

One can see why Mort, in particular, would make a good translator for Cimafiejeva. Reading Motherfield, I often thought of a comment that she makes in a conversation with Polina Barskova. It comes in reference to Mort’s virtuosic translation of Barskova’s Air Raid (2022) — a book which is, unlike Cimafiejeva’s, originally in Russian, but which breaks the orthodoxies of Russian grammar:

“Both English and Russian are imperial language systems used to justify violence. This commonality makes the breaking translatable, particularly by a translator like me, for whom Russian is a stepmother tongue, an imposed, colonial language. When I translate [Barskova’s] work, I get to break Russian while wearing the gloves of English — I’m an untraceable Belarusian criminal.”

Mort and Abdurraqib’s task in translating Cimafiejeva is different, of course: it’s less about breaking “Russian while wearing the gloves of English” and more about finding a way to bring Belarusian poetry into English without allowing the imperial language to exert its gravitational force, disrupting and domesticating Cimafiejeva’s work. Their resulting translation is fluid and loose, embracing an idiomatic and sarcastic English. “Wow, embarrassing,” ends the first stanza of their translation of Cimafiejeva’s “Circus.” But it is also capable of elegant, high diction — often in the same poem. A stanza later, “Circus” has leapt into a kind of Biblical gravitas: “But the swamp begot / fields of beets, / potato beetles, / indigenous proverbs.” In Mort and Abdurraqib’s translations, Cimafiejeva’s poems refuse to settle into a stable, accessible, workshopped voice. Instead, they are resourceful, fluid, and mobile. English itself — and the expectations of English-language poetry readers — are denaturalized, destabilized.

No doubt, it helps that Cimafiejeva uses English herself, strategically, as a language of resistance. Her diaries were written — and published — in English, as was the final poem in the book “My European Poem.” (Both the diary and the poem have been lightly edited by Mort and Abdurraqib). As she observes in a recent interview with the Poetry Foundation, “The English language gave me this distance from what was going on to me. So it was not like me. It was like someone else. I was like, watching a film …” After finishing the book, however, Cimafiejeva tried, and failed, to translate it into Belarusian: “The problem is that this book can be dangerous to me, but also for those people who I write about. And some of them are still in Belarus … And maybe Belarusian authorities do not read so eagerly in German or in English, or in the Dutch language, but they do read in Belarusian.” As Cimafiejeva writes in “My European Poem” (also originally in English):

I can’t say that in Belarusian

I can’t say that in Russian,

I can’t say that in Ukrainian,

Only in English: I am afraid,

Only in German: Ich habe Angst,

Only in Norwegian: Jeg er redd.

One must be careful, then, to avoid an overly simplistic reading of the gesture these poems make. Writing in Belarusian is not, in any simple or uncomplicated way, liberatory: the regime exerts its power in and through Belarusian as much as Russian. Nor is writing in English necessarily liberatory. Both languages are strategic resources. Cimafiejeva advances into one language, then into the other, as its suits her literary and political purposes. In the context of Lukashenko’s repression, it is necessary to move fluidly, to be resourceful, to employ multiple strategies of resistance: “‘Be like water’ is another slogan of our protests,” Cimafiejeva observes, “the same as the one used by Hong Kong protesters.”

I should end this review by reminding you that Lukashenko remains in power, that he has allowed Russian troops to use Belarus as a staging ground for their brutal invasion of Ukraine, that his critics remain in jail or in exile, political leaders, poets, and ordinary Belarusians alike. I should end with these facts because they demand iteration: they should be said until forgetting becomes impossible. I should say it: although Motherfield is an urgent call to remember the bravery and the sacrifices of those who have resisted the Lukashenko regime, I do not think that it is primarily addressed to the amnesia of Western readers, an attempt to rouse us from our stupor. In the closing stanza of “My European Poem,” written on August 5, 2020, two days before the stolen 2020 election, Cimafiejeva begins by apologizing to Western readers: “forgive me my nagging in a half-broken English, / My Eastern European never-ending complaints.” But she leaves those readers behind and closes the poem— and her book — with a specific wish for Belarus, and for the Belarusian language:

I should end this review by reminding you that Lukashenko remains in power, that he has allowed Russian troops to use Belarus as a staging ground for their brutal invasion of Ukraine, that his critics remain in jail or in exile, political leaders, poets, and ordinary Belarusians alike. I should end with these facts because they demand iteration: they should be said until forgetting becomes impossible. I should say it: although Motherfield is an urgent call to remember the bravery and the sacrifices of those who have resisted the Lukashenko regime, I do not think that it is primarily addressed to the amnesia of Western readers, an attempt to rouse us from our stupor. In the closing stanza of “My European Poem,” written on August 5, 2020, two days before the stolen 2020 election, Cimafiejeva begins by apologizing to Western readers: “forgive me my nagging in a half-broken English, / My Eastern European never-ending complaints.” But she leaves those readers behind and closes the poem— and her book — with a specific wish for Belarus, and for the Belarusian language:

I still want to have a hope,

I still believe I have a right to a hope,

That beaten hope that builds its nest

On my roof and signs

In Belarusian

(Not in Russian).

It would’ve been easy to begin the book with this poem, offering it as a preface to Cimafiejeva’s protest diaries — hope that dissolves or fades as Lukashenko’s police violently suppress the protests. By ending the book here, just before the protests begin, Cimafiejeva might be said to insist on the persistence of that hope, even now: to paraphrase Walter Benjamin, every moment be the narrow gate through which a new Belarus arrives.

[Published by Deep Vellum on November 22, 2022, 128 pages, $18.95 paperback]

[i] Vera Rich, translator and editor of Like Water, Like Fire, a Soviet-era anthology of Belorussian poetry, describes Kupala as “generally accepted to be the ‘National poet’ of Byelorrusia”; according to Rich, Kolas and Kupala shared the title of “People’s poet of the Byelorussian SSR” in the late 1920s.

/ / /

To read five poems from Motherfield, published earlier On The Seawall, click here.