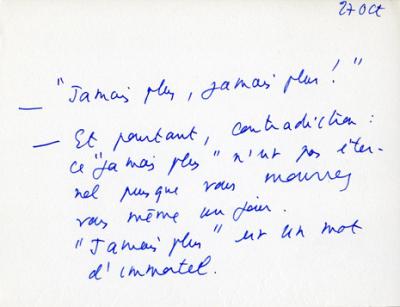

Roland Barthes lived near or with his mother Henriette for most of his life. Starting the day after she died on October 25, 1977 and continuing for the next two years, Barthes expressed and probed his grieving by jotting notes on slips of paper. Out of this stack of notes came the second half of Camera Lucida, his extended essay on photography, begun in the spring of 1979.

June 9, 1978. This morning, walking through Saint-Sulpice, whose simple architectural vault delights me; to be in architecture – I sit down for a moment; a sort of instinctive prayer: that I finish the Photo-Maman book. And then I notice that I am always asking for something, wanting something, always pulled ahead by childish Desire. One day, to sit in the same place, to close my eyes and ask for nothing … Nietzsche: not to pray, to bless. Is it not to this that mourning should lead?

June 9, 1978. This morning, walking through Saint-Sulpice, whose simple architectural vault delights me; to be in architecture – I sit down for a moment; a sort of instinctive prayer: that I finish the Photo-Maman book. And then I notice that I am always asking for something, wanting something, always pulled ahead by childish Desire. One day, to sit in the same place, to close my eyes and ask for nothing … Nietzsche: not to pray, to bless. Is it not to this that mourning should lead?

But on July 31, when he writes this one-sentence note – “I ask for nothing but to live in my suffering” – and this fragment on September 13 – “The grim egotism of mourning and suffering” – it appears that Barthes’ may want his mourning to lead elsewhere, but that slips of paper, his typing sheets cut neatly into quarters, may be the only elsewhere he has access to. This document is ultimately about the urgencies of writing, “a diagnostic test,” as Richard Howard says, through which Barthes tries to discover the felt aspects of mourning that are missing from his words. Barthes writes, “I transform ‘work’ in the psychoanalytic sense (work of mourning, dreamwork) into the real work – of writing.” Barthes’ discoveries occur, as he says, “at the level of language itself – which is simply: writing.”

Howard continues: “It became, this multiplication of feuilles, a realization that yet another kind of utterance might, eventually, be constituted out of this deprivation, this dispossession, this travail; such a book was never written.”

Howard continues: “It became, this multiplication of feuilles, a realization that yet another kind of utterance might, eventually, be constituted out of this deprivation, this dispossession, this travail; such a book was never written.”

On March 15, 1979, Barthes writes that his “anything but spectacular mourning has kept me unceasingly separate by its demands; a separation that I have ultimately always projected to bring to a close by a book — Stubbornness, secrecy.” And so he had a way of convincing and luring himself into language, since that was where the drama would unfurl — but of course, the allegedly desired end to the separation, between the man watching himself grieve and the language used to describe him doing it, would never occur.

Situated at the center of his grief, he can’t see it. It isn’t observable but constantly present. Some of the notes cry out for the mother and recall moments together. Others are analytical, especially those probing the fright he feels in his aloneness.

October 6, 1978. FEAR: always confirmed – and written – as a central feature in my case. Before maman’s death, this Fear: fear of losing her. And now that I’ve lost her? I’m always in FEAR, and perhaps even worse, for, paradoxically, still more fragile (hence my insistence on withdrawal, in other words, discovering a place completely protected from Fear).

Fear, then, but of what, now? – Of dying myself? Yes, most likely – But, apparently, less – I feel this – for dying is what maman has done (benevolent ghost of: joining her)

Hence, actually: Winnicott’s psychotic, I fear a catastrophe that has already occurred. I constantly perpetuate it in myself under a thousand substitutions.

Critics have described these notes as “aphoristic,” but they read more like agitations, made all the more poignant by a bruised avidity. There is much repetition, since Barthes keeps returning to notions that won’t simply surrender to depth of feeling, which in turn is questioned: “November 10. Embarrassed and almost guilty because sometimes I feel that my mourning is merely a susceptibility to emotion. But all my life haven’t I been just that: moved?”

Mourning Diary arrives as an opportunity to recall how much pleasure you took in Barthes, if you did, and to ride the leap from disorderly fragments to the fluent surprises of Camera Lucida in which Barthes considers a photograph of his mother taken in 1913. Watch for linkages between and extensions from the excerpts below. First, notes from May 18 and May 25, 1978, that debate with each other:

Mourning Diary arrives as an opportunity to recall how much pleasure you took in Barthes, if you did, and to ride the leap from disorderly fragments to the fluent surprises of Camera Lucida in which Barthes considers a photograph of his mother taken in 1913. Watch for linkages between and extensions from the excerpts below. First, notes from May 18 and May 25, 1978, that debate with each other:

Maman’s death: perhaps it is the only thing in my life that I have not responded to neurotically. My grief has not been hysterical, scarcely visible to others (perhaps because the notion of “theatrilizing” my mother’s death would have been intolerable); and doubtless, more hysterically parading my depression, driving everyone away, ceasing to live socially, I would have been less unhappy. And I see that the non-neurotic is not good, not the right thing at all …

When maman was living (in other words, in my whole past life) I was neurotically in fear of losing her. Now (this is what mourning teaches me) such mourning is so to speak the only thing in me which is not neurotic: as if maman. By a last gift, had taken neurosis, the worst part, away from me.

These painful, groping notes evolve into the following sentences from Camera Lucida which meditate on the fact of time itself and relocate the hysteria:

Thus the life of someone whose existence has somewhat preceded our own encloses in its particularity the very tension of History, its division. History is hysterical: it is constituted only if we consider it, only if we look at it – and in order to look at it, we must be excluded from it. As a living soul, I am the very contrary of History, I am what belies it, destroys it for the sake of my own history (impossible for me to believe in “witnesses”; impossible, at least, to be one) …

Thus the life of someone whose existence has somewhat preceded our own encloses in its particularity the very tension of History, its division. History is hysterical: it is constituted only if we consider it, only if we look at it – and in order to look at it, we must be excluded from it. As a living soul, I am the very contrary of History, I am what belies it, destroys it for the sake of my own history (impossible for me to believe in “witnesses”; impossible, at least, to be one) …

Hill and Wang is about to issue new editions of Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, and A Lover’s Discourse, the great works of Barthes’ later career. If you’re thinking of revisiting or getting acquainted with these texts, Mourning Diary may be the best place to start.

[Published by Hill and Wang on October 19, 2010. 261 pages, $25.00 hardcover]