A probate record filed in Suffolk County, Massachusetts in 1661 lists “An Inventory of all such Goods Mr John Stoughton died possest of.” His estate included the following:

1 Stone horse, 1 Gelding Lame & Sickly

one man Negro named John & one Negro boy named Peter

One beam Scales & 882 of Leaden waights

Three bbs flower, 2 firkins of butter, bad

In her engagingly discerning and vividly argued new book New England Bound, Wendy Warren uses details from deeds, wills, estate inventories, diaries, shipping invoices, court testimony and other period documents to illustrate the entrenched presence of chattel slavery in 17th century New England. She estimates that enslaved people comprised 5-10 percent of the region’s largest towns.

This is not the history I learned in the public schools of Quincy, Massachusetts in the 1960’s. The state’s outlawing of slavery in 1783 seems to have erased the Commonwealth’s memory as well. My teachers directed my attention to the abolitionist sentiments and slave-liberating narratives of Civil War history. So now it must be asked: why was the memory of chattel slavery repressed? For what purposes can we use our awakened awareness of it?

This is not the history I learned in the public schools of Quincy, Massachusetts in the 1960’s. The state’s outlawing of slavery in 1783 seems to have erased the Commonwealth’s memory as well. My teachers directed my attention to the abolitionist sentiments and slave-liberating narratives of Civil War history. So now it must be asked: why was the memory of chattel slavery repressed? For what purposes can we use our awakened awareness of it?

“Even as our understanding of the colonial process in the region has grown more complicated, there has remained something exceptional in both the popular and the scholarly understanding of early colonial New England, an exceptional absence,” she writes. “Put plainly, it is this: the tragedy of chattel slavery – inheritable, permanent, and commodified bondage – the problem that dominates the narrative of so many other early English attempts at colonization in North American and the Caribbean, hardly appears in the story of earliest New England.”

It is not a secret that New England households exploited slave labor for 150 years. But the actuality was softened and suppressed by regarding such communities as “societies with slaves” unlike the “slave societies” of southern plantations. In other words, slaveholding in the north was treated as a sort of flagrant misdemeanor, not as reflection of broader society. Warren acknowledges that northern households and farms rarely included more than two or three slaves. There are critical distinctions between northern and southern slavery practices. However, her investigation shows that slavery was codified into a range of New England laws and customs.

It is not a secret that New England households exploited slave labor for 150 years. But the actuality was softened and suppressed by regarding such communities as “societies with slaves” unlike the “slave societies” of southern plantations. In other words, slaveholding in the north was treated as a sort of flagrant misdemeanor, not as reflection of broader society. Warren acknowledges that northern households and farms rarely included more than two or three slaves. There are critical distinctions between northern and southern slavery practices. However, her investigation shows that slavery was codified into a range of New England laws and customs.

Although Warren relies on archival sources, New England Bound succeeds through story, a multi-vectored inquiry, sharpness of prose, and a dignified passion for rectification. To begin, she digs into the question of how African people arrived in New England in the first place and uncovers a barely examined aspect of the region’s past – the connection between the merchants of Massachusetts and the sugar plantations of Barbados. Shipping fish, beef, pork and farm produce to the Caribbean, New England dramatically grew its economic base to such a degree that in 1660 an English sea captain named Thomas Bredon noted “they being the key of the Indies without which Jamaica, Barbados & the Caribee Islands are not able to subsist.”

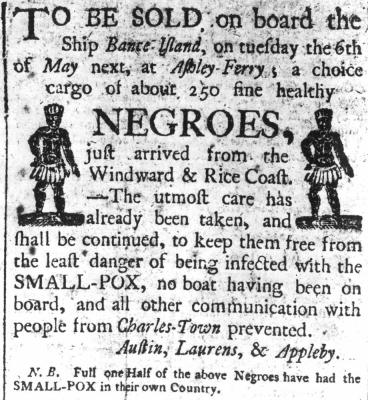

Warren states bluntly, “New England commodities provided the energy that was consumed and then burned calorie by calorie in slave labor, converted ultimately into a commodity perfect for the world market.” Eventually, economic power in Boston led to political disobedience. The Revolution’s taproot extended far south. But for 150 years before declaring independence, wealthy New England merchants interacted continuously with and invested in plantation societies, and their ships brought purchased slaves northward to New Haven, New Bedford and Boston. By the time chattel slavery reached its peak in the mid-1700’s, the fifth, sixth and seventh generations of enslaved people had struggled and suffered in towns.

Having established the foundation of her narrative, Warren moves to describe the lives of those enslaved and their relations among the families and farms of New England. But New England Bound also takes up the situation of native tribes people, not only driven from their lands but also shipped out as slaves to the West Indies or made captives. When the Pequot War ended in 1637, a group of male captives was taken out to sea and deliberately drowned according to the account of a William Hubbard. Warren continues, “Women and children were given away to allied Indian nations … Their new masters agreed to make yearly payments to the English in exchange for the captives. Here was another way bodies might be commodified.” The treaty specified, “The Country that was formerly theirs … now is English by Conquest.”

Having established the foundation of her narrative, Warren moves to describe the lives of those enslaved and their relations among the families and farms of New England. But New England Bound also takes up the situation of native tribes people, not only driven from their lands but also shipped out as slaves to the West Indies or made captives. When the Pequot War ended in 1637, a group of male captives was taken out to sea and deliberately drowned according to the account of a William Hubbard. Warren continues, “Women and children were given away to allied Indian nations … Their new masters agreed to make yearly payments to the English in exchange for the captives. Here was another way bodies might be commodified.” The treaty specified, “The Country that was formerly theirs … now is English by Conquest.”

Warren also takes up the question of how Puritan theology accommodated the practice of slavery. Cotton Mather had proclaimed, “There must be a Superiority and an Inferiority; there must be some who are to Command, and there must be some who are to Obey. The hierarchies of The Great Chain of Being, the bread and butter of empire and theology, dominated the 17th century thinking. Warren explains, “Puritan theology had no existential distaste for slavery, no more than did Anglicanism. The sermons of Puritan ministers legitimized bondage and differentiated it from term servitude. At the time of his death in 1723, Increase Mather was a slave owner; his will specified that his black slave should receive his liberty and ”let him then be esteemed a Free Negro.”

In the north, slaves lived in close quarters with their owners – and the misdemeanors of slaves (and their punishments) were noted in public records. The second half of New England Bound, focusing on the relations between master and slave, unfurls a number of stories that add a gritty dimension to the history.

In the north, slaves lived in close quarters with their owners – and the misdemeanors of slaves (and their punishments) were noted in public records. The second half of New England Bound, focusing on the relations between master and slave, unfurls a number of stories that add a gritty dimension to the history.

Warren mentions a passage in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The American Notebooks written in 1838 in which he expresses astonishment at seeing black people among the crowds gathered at the Williams College commencement. He overheard an old man speaking with a “strange kind of pathos, about the whippings he used to get, while he was a slave – a queer thing of mere feeling, with some glimmerings of sense.” The passage ends with this illuminating statement: “I find myself rather more of an abolitionist in feelings than in principle.” The dire workings of New England slavery had faded from memory even then.

[Published June 7, 2016. 368 pages, $29.95 hardcover]