Hunter of Stories by Eduardo Galeano, translated by Mark Fried (Nation Books/Hachette)

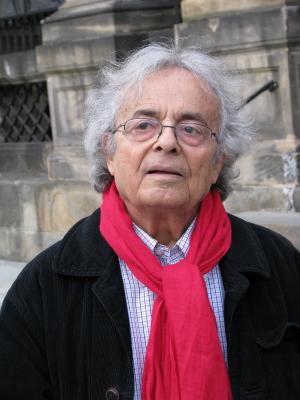

Concerto al-Quds by Adonis, translated by Khaled Mattawa (Yale University Press)

Magnetic Point: Selected Poems 1968-2014, by Ryszard Krynicki, translated by Clare Cavanagh (New Directions)

* * * * *

“There are some writers who feel they are elected by God,” said Eduardo Galeano in a 2013 interview. “I am not. I am elected by the devil, this is clear.” When he died two years later at age 74 in Montevideo, his obituaries often focused on his 1971 book Open Veins (Las Venas Abiertas de América Latina) which tracks five centuries of economic exploitation in the Americas. When a military junta took power in Uruguay in 1973, the book was banned and Galeano was jailed. Nevertheless, millions of copies of Open Veins were sold while Galeano lived in exile in Argentina and then Spain. In 2014, he remarked that he no longer felt closely connected to the book – not because of its politics but its style. “It’s hard for me to recognize myself in it since I now prefer to be increasingly brief and untrammeled,” he said.

Over the decades, his practice of “alternative historiography” merged with his urge to tell stories. Scott Sherman described Galeano’s trilogy Memory of Fire (1982-86) as “a kind of secret history of the Americas, told in hundreds of kaleidoscopic vignettes that resurrected the lives of campesinos and slaves, dictators and scoundrels, poets and visionaries. Memoirs, novels, bits of poetry, folklore, forgotten travel books, ecclesiastical histories, revisionist monographs, Amnesty International reports — all of these sources constituted the raw material of Galeano’s sprawling mosaic.” Michael Dirda said Galeano “rivals such masters of the fable as Kafka.”

Over the decades, his practice of “alternative historiography” merged with his urge to tell stories. Scott Sherman described Galeano’s trilogy Memory of Fire (1982-86) as “a kind of secret history of the Americas, told in hundreds of kaleidoscopic vignettes that resurrected the lives of campesinos and slaves, dictators and scoundrels, poets and visionaries. Memoirs, novels, bits of poetry, folklore, forgotten travel books, ecclesiastical histories, revisionist monographs, Amnesty International reports — all of these sources constituted the raw material of Galeano’s sprawling mosaic.” Michael Dirda said Galeano “rivals such masters of the fable as Kafka.”

His translator, Mark Fried, says that in the final three years of his life Galeano would write for “a few hours every day sitting quietly alone, pen and pad in hand, as he traveled across Latin America, Europe and the United States for public appearances.” The result is Hunter of Stories, a far ranging, poignant, sometimes enigmatic and ever provocative collection of short pieces.

THE ACTIVIST

Laudelia de Campos Mello, granddaughter of slaves, was born in 1904.

From the age of twelve she had to take charge of her five younger brothers.

Her black skin did not help her find employment in the city of Sao Paulo, but she managed to cook and clean in several private homes, from dawn to dusk, taking her brothers with her.

Granny Nina, as she became known, was twenty when she was elected president of the domestic workers’ union.

From then on, she dedicated her life to helping women who, like her, were born already condemned to perpetual servitude.

She died at the age of eighty-six.

At her funeral there were no speeches.

All of her fellow workers were there and they said goodbye with a song.

Many of these pieces touch on the arts and culture, leavened by his comic spirit.

THE MUSICIAN

In Kanchi, holy city of the Tamils of India, lived and dreamed the most off-key flutist in the world.

He was paid very well to play very poorly.

In the service of the gods, his flute tormented the devils.

The inhabitants of Kanchi kept him chained to a tree so he would not run away. From Kerala, Myore, and other places fabulous offers rained down.

Everyone wanted the master of the impenetrable art of being awful.

In “Why I Write” he says, “I would say that I write hoping to make us all stronger than our fear of failure or of punishment when it comes to choosing sides in the eternal battle of indignation against indignity.” In an unattributed introduction to a 2000 interview in The Atlantic, it was said that “More than most writers, Galeano walks the tightrope between poet and pamphleteer.” True, he never backed away from the most obvious ironies, and even in the more fanciful pieces in Hunter of Stories, his moral clarity is evident – as well as his devilish agenda.

In “Why I Write” he says, “I would say that I write hoping to make us all stronger than our fear of failure or of punishment when it comes to choosing sides in the eternal battle of indignation against indignity.” In an unattributed introduction to a 2000 interview in The Atlantic, it was said that “More than most writers, Galeano walks the tightrope between poet and pamphleteer.” True, he never backed away from the most obvious ironies, and even in the more fanciful pieces in Hunter of Stories, his moral clarity is evident – as well as his devilish agenda.

A STORYTELLER TOLD ME

Once upon a time, somewhere in the jungle of Africa, lived a lion king, gluttonous and imperious.

The king forbade his subjects from eating grapes. “Only I may eat grapes,” he decreed, and he signed a royal proclamation that his monopoly was the will of the gods.

The rabbit, deep in the thicket, then kicked up a tremendous ruckus, breaking branches, swinging from vines, screaming, “Even elephants will fly! The wind is going crazy! There’s a hurricane coming!”

The rabbit urged the animals to protect the monarch by tying him to the stoutest tree.

Thus the lion king, tightly bound, was saved from the hurricane that never arrived, while the rabbit, scampering about the jungle, left not a single grape uneaten.

[Published November 14, 2017. 272 pages, $26.00 hardcover]

* * * * *

“Jerusalem fever,” wrote James Carroll, “consists in the conviction that the fulfillment of history depends on the fateful transformation of the earthly Jerusalem into a screen onto which overpowering millennial fantasies can be projected.” Every three days, a patient is committed to the city’s psychiatric hospital with “Jerusalem Syndrome,” a temporary insanity caused by visiting sacred sites. Muslims, Christians, and Jews encumber the arid city with proprietary myths and claims. Who will weep or praise or hope on behalf of the actual city? Who will gather all the separate histories and torments into a single vision of yearning for the neglected glory in the actual moment?

In 2010, just before his Selected Poems appeared in Khaled Mattawa’s translation from the Arabic, Adonis told Charles McGrath of The New York Times, “The textbooks in Syria all say that I have ruined poetry” because of his use of unrhymed variable lines and willful inclusion of prose. McGrath continued, “He went on to complain about what he called the ‘retardation’ of Arabic poetry, which in his view has become a rhetorical tool for explaining the political and religious status quo.”

In 2010, just before his Selected Poems appeared in Khaled Mattawa’s translation from the Arabic, Adonis told Charles McGrath of The New York Times, “The textbooks in Syria all say that I have ruined poetry” because of his use of unrhymed variable lines and willful inclusion of prose. McGrath continued, “He went on to complain about what he called the ‘retardation’ of Arabic poetry, which in his view has become a rhetorical tool for explaining the political and religious status quo.”

It was around this time, while drafting a long poem called “Concerto for al-Quds,” that Adonis announced his retirement from poetry. Al-Quds are the Arabic words for Jerusalem. At age 82 in 2012, he told Maya Jaggi at The Guardian, “Jerusalem is a city of three monotheistic religions. If there’s one God, it should be beautiful. Instead, it’s the most inhuman city in the world. I said I was stopping poetry as an act of defiance. But the pre-monotheistic goddess didn’t let me retire.”

Originally published in 2012, Concerto for al-Quds dares to counter Jerusalem Fever with a profoundly humane delirium of its own — a series of voices (or one throat with many speeches), some rueful and desirous, others contentious and critical. Places are named and described, the patriarchs and prophets of holy texts are addressed for their lyrical promises and critiqued for the intolerance they inspire.

The concerto has two movements – “The Meaning” and “Images” – each comprising several parts. The first part includes the multi-part poem “A Bridge To Job.” “A Saying,” below, is the seventh of nine sections:

What wall are you pointing to, Book of Job?

This wall rises from sand that was never a labyrinth. It was once a sail, and in it the gold of law blended with the silver of architecture.

It has fallen from towers that abut planets obscuring any possibility of a horizon. And now it stands as a rubble of barbed wire, a recklessness filling the air’s skull.

The wall lives multiple lives in this ephemerality, this earth. In the hereafter it will be merely a military shirt, a guarding a camp filled with captives being tortured by divine executioners.

Anxiety fills a northern crack in the wall, shaded by words that know the unknown and sleep that resembles waking. The sun dares to confess her age and infirmity. And in the shadow of the wall, the sun looks out from a window facing the Mediterranean – a sea that has no middle ground, only tomb or sky.

But how close the tomb appears!

And how distant the sky!

What can I say?

No, there is no sky anymore.

No Sama’.

The Seen is a sword, the Mim mortality,

the Alifs are an oppressive ancestry.

The glottal stop a vast emptiness.

Mattawa provides a meticulously informative section of notes, underscoring Adonis’ wish to erect an unconventional al-Quds made from the conventional reference points of wall-builders and prayer-abusers. In the segment above, “the silver of architecture” refers to a wise commentary by Maimonides. The phrase “a sea that has no middle ground” plays on an Arabic translation of the word “Mediterranean” that notes the waters’ fairness and moderation, qualities that no longer pertain. Finally, Sama is the Arabic word for “sky.”

“Undermining the authority of the discourses of intolerance has long been a preoccupation of Adonis,” writes Mattawa, noting that the poet has channeled and updated the lyricism of Sufi poets with fresh diction and formal inventiveness. Adonis has insisted on his right to creatively appropriate history, wresting it from ideology and partisan aims. Politically speaking, it has seemed at times that he can please no one. In 2015 upon winning Germany’s Goethe Prize, he was criticized for not voicing enough support for Syrian revolutionaries. “I’m against an ideology based on a singleness of ideas,” he told The Guardian. “A creator always has to be with what’s revolutionary, but he should never be like the revolutionaries. He can’t speak the same language or work in the same political environment.”

“Undermining the authority of the discourses of intolerance has long been a preoccupation of Adonis,” writes Mattawa, noting that the poet has channeled and updated the lyricism of Sufi poets with fresh diction and formal inventiveness. Adonis has insisted on his right to creatively appropriate history, wresting it from ideology and partisan aims. Politically speaking, it has seemed at times that he can please no one. In 2015 upon winning Germany’s Goethe Prize, he was criticized for not voicing enough support for Syrian revolutionaries. “I’m against an ideology based on a singleness of ideas,” he told The Guardian. “A creator always has to be with what’s revolutionary, but he should never be like the revolutionaries. He can’t speak the same language or work in the same political environment.”

This is his language in Concerto al-Quds: “Walls overfill with the hemispheres and empty their own secrets. A universe of straw and sulfur. Idols ally and conspire against human speech. Puppets slaughter each other below them. Here and there a stage to impale human beings on angel horns.”

[Published November 28, 2017. 96 pages, $25.00 hardcover]

* * * * *

“Act of Birth,” the opening poem in Ryszard Krynicki’s first book of poems of that title published in 1969, reads in Clare Cavanagh’s translation from the Polish:

born in transit

I came upon on the place of death

the cult of the individual unit

of measures

and weights

the military unit

progressive paralysis

paralyzing progress

each day I listen to

the latest news

I live

in the place of death

The poem conflates two moments. The first refers to his birth in 1942 in a Nazi work camp near Mauthausen in Austria where his Polish parents worked as slave laborers in a tank factory. The second occurs in the present tense, but “the place of death” now extends to all of Soviet-ruled Poland. Along with Adam Zagajewski, Stanislaw Barańczek, and Ewa Lipska, Krynicki was a rising poet of the “Generation of ’68,” dissenters objecting to the state’s prohibitions of expression and other freedoms. In her introduction to Krynicki’s Magnetic Point: Selected Poems 1968-2014, Cavanagh writes, “While Zagajewski embraced the Krakow school of poetic ‘straight speaking,’ both Barańczek and Krynicki represented what came to be known as the Poznanian ‘linguistic school’… Krynicki’s distinctive brand of ‘socialist surrealism’ draws on the incongruities between the daily realities of People’s Poland and the ideology that claims to represent them.” The barren existence of socialist conformity triggered outbursts of rebellious derision in his work.

The poem conflates two moments. The first refers to his birth in 1942 in a Nazi work camp near Mauthausen in Austria where his Polish parents worked as slave laborers in a tank factory. The second occurs in the present tense, but “the place of death” now extends to all of Soviet-ruled Poland. Along with Adam Zagajewski, Stanislaw Barańczek, and Ewa Lipska, Krynicki was a rising poet of the “Generation of ’68,” dissenters objecting to the state’s prohibitions of expression and other freedoms. In her introduction to Krynicki’s Magnetic Point: Selected Poems 1968-2014, Cavanagh writes, “While Zagajewski embraced the Krakow school of poetic ‘straight speaking,’ both Barańczek and Krynicki represented what came to be known as the Poznanian ‘linguistic school’… Krynicki’s distinctive brand of ‘socialist surrealism’ draws on the incongruities between the daily realities of People’s Poland and the ideology that claims to represent them.” The barren existence of socialist conformity triggered outbursts of rebellious derision in his work.

CITIZEN R. K. DOESN”T LIVE

Citizen R. K. doesn’t live

with his wife (or any object

that is his own), he doesn’t live by the pen,

by the indigestible fountain pen marked “Parker”

that sticks in his throat: he is a sado-

(he gulps the ink that streams

from the fountain pen marked “Parker”)

masochist (with this pen he revives the corpses

of days gone by, so as to harass

them): born (he doesn’t

know why): into a worker’s family, but just the same

he freeloads (on speech): an honorary

blood donor (does foreign blood flow

in his veins): against our

death penalty: he tried to smuggle

something across the border: a birth

certificate, his collective

organism, and a fountain pen (“Parker”): he

doesn’t jot down thoughts, he communicates telepathically

(there’s a snake

in his telephone) and he corrupts underaged

wristwatches: to fall asleep he counts to 19

84 (isn’t he counting on nothing?). He lives,

though it remains unclear

whether he deserves such a life

From December 1981 to July 1983, the Polish state apparatus unleashed martial law to crush political opposition. Zagajewski fled to Paris and Barańczek wound up at Harvard – but Krynicki stayed on, publishing his work clandestinely through underground presses. His poems became even more terse and punchy, “a stripped down, gnomic poetry,” brief jolts of observation that seem to ask the reader to stop, contemplate, and find one’s inner resistance.

PURGATORIUM

Night, an empty compartment. I want

nothing, fear no one. Glowing in the distance,

the little flames of purgatory: my city.

Herbert, Milosz, Symborska and Zagajewski have all been celebrated and studied in the United States, but not Krynicki, probably because of his disinterest in self-portrayal and limited patience for the cultivation of sentiment. His poetry had a nose for sniffing out the close proximity of the enemy — the stench stiffened his spine. But he was anything but an editorialist posing as a poet, and his vision generously extended to everything around him. Even as the political turmoil cooled down in Poland, his sensibilities retained their intensity:

Herbert, Milosz, Symborska and Zagajewski have all been celebrated and studied in the United States, but not Krynicki, probably because of his disinterest in self-portrayal and limited patience for the cultivation of sentiment. His poetry had a nose for sniffing out the close proximity of the enemy — the stench stiffened his spine. But he was anything but an editorialist posing as a poet, and his vision generously extended to everything around him. Even as the political turmoil cooled down in Poland, his sensibilities retained their intensity:

SECRETLY

Secretly, discreetly

I lift my older brother,

the snail,

from the path,

so that no one will step on him.

Older by a million years or so.

Brother in uncertain existence.

Both alike not knowing

what we were created for.

Both alike writing mute questions,

each in his most intimate script:

Frightened sweat, sperm, mucus.

[Published November 15, 2017. 226 pages, $18.95 paperback]