Of the French poets who launched the influential culture and arts magazine L’Éphémère in 1966, Yves Bonnefoy and Paul Celan are the ones most familiar to Anglophone readers. Limited selections of the poetry of their colleague, André du Bouchet, translated by Paul Auster and David Mus, were published respectively in 1976 and 2000. The publication of Openwork, a more generous representation of du Bouchet’s work, provides an opportunity to consider the life and accomplishments of a poet who may be the more influential of the three for younger poets.

Throughout the 1960’s, even two decades after World War II had ended, a group of dynamic French poets was still struggling with the trauma and wreckage of those events. In 1946, Pierre Reverdy declared that poetry must realign itself “in keeping, from now on, with the importance and gravity of the event it has just lived.” Yves Bonnefoy later recalled, “The event of war itself, its brute reality, was far more important for me, from the perspective of the poetic experience, than the interpretations that were being offered.” Retaining its power as an unspeakable event, the war’s psychic residue – and the social and historical narratives designed to brush it aside — dared writers to discover a newly adequate language.

Throughout the 1960’s, even two decades after World War II had ended, a group of dynamic French poets was still struggling with the trauma and wreckage of those events. In 1946, Pierre Reverdy declared that poetry must realign itself “in keeping, from now on, with the importance and gravity of the event it has just lived.” Yves Bonnefoy later recalled, “The event of war itself, its brute reality, was far more important for me, from the perspective of the poetic experience, than the interpretations that were being offered.” Retaining its power as an unspeakable event, the war’s psychic residue – and the social and historical narratives designed to brush it aside — dared writers to discover a newly adequate language.

Where the devastations of World War I yielded the provocations and parodies of Surrealism and the disturbed speechiness and imagistic observances of Modernism, the subsequent war threw many European poets back on their heels. Yet while Theodor Adorno proclaimed the end of poetry’s viability, the poets themselves responded by pursuing a new opening, however narrow and dubious. It is what Celan called “the impossible path of the Impossible.”

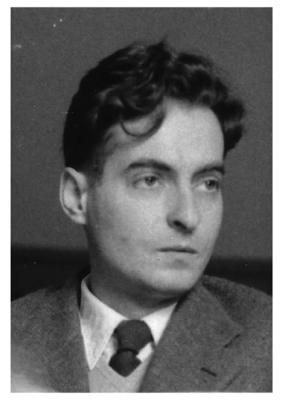

Born in the early 1920’s, Bonnefoy, Celan and du Bouchet experienced the war years in their early adulthood, and their poetry recalls and incorporates the sweeping away of the security, standards and safeguards of their youth. But du Bouchet’s experience is especially telling. In December 1940, he and his family left Europe on the last passenger ship to depart westward from Lisbon. His mother, a physician, was Jewish; his father was incapacitated by schizophrenia and institutionalized during much of his life. Because the mother’s credentials were invalid in America, she took medical courses and lived in hospital residence rooms, while du Bouchet and his sister attended boarding school. He went on to Amherst College on a scholarship, majored in literature and mastered English, made friends with fellow student James Merrill, earned his BA summa cum laude in three years, and proceeded to Harvard.

Born in the early 1920’s, Bonnefoy, Celan and du Bouchet experienced the war years in their early adulthood, and their poetry recalls and incorporates the sweeping away of the security, standards and safeguards of their youth. But du Bouchet’s experience is especially telling. In December 1940, he and his family left Europe on the last passenger ship to depart westward from Lisbon. His mother, a physician, was Jewish; his father was incapacitated by schizophrenia and institutionalized during much of his life. Because the mother’s credentials were invalid in America, she took medical courses and lived in hospital residence rooms, while du Bouchet and his sister attended boarding school. He went on to Amherst College on a scholarship, majored in literature and mastered English, made friends with fellow student James Merrill, earned his BA summa cum laude in three years, and proceeded to Harvard.

The losses described by du Bouchet, dramatized by his exile from France, were the same ones suffered by his fellow younger poets who lived through the war in Europe. The world he had “hardly begun to discover had been destroyed.” As a poet, his role was “to reestablish something, to account for a relation that, even before I could really notice it – I was barely 15 years old – was swept away.” His poetry would comprise “words of rupture … insolence of a breath that proffers … and vanishes.”

Written in the United States between 1946 and 1948, his first poems were published in The New Republic, The Yale Review, and The Partisan Review. After returning to Paris in 1948, his work was welcomed in Jean-Paul Sartre’s Les temps modernes in 1949. Below, an early poem titled “Term” (“Vocable”):

Everything becomes words

earth

pebbles

in my mouth and under my feet

man given back

redeemed

in stones

in coins

of gold

currency of words and steps

what I say makes you laugh

nameless

gold that barters me

alive.

“His separation from French had created in him a dual consciousness,” writes Hoyt Rogers in his introduction, “a distance that encouraged him to approach his own language freshly, testing and stretching its possibilities as only an ‘outsider’ can do. At a deeper level, he had entered the interstices where silence cohabits with speech. In a conversation les than a year before his death [in 2001], he recalled that in this period English was the language in which he ‘didn’t sputter,’ whereas French was then language of intimacy, ‘of everything that belonged to the order of muteness … a foreign language, inaccessible because too close.’”

The question for Bonnefoy, Celan and du Bouchet, among others, was: How do I regain possession of myself? Conventional narrative lyricism was out of the question and surrealism was bankrupt. Bonnefoy said that the poets’ “affective powers and our thought are too heavily marked by past events, which are so fearsomely established as givens and almost as things.” Thus annulled, the poetic would no longer proceed through familiar forms and sounds. The authority of the heroic speaker was eroded; the language would aspire upwards from the lowest of baselines and then dissipate.

The question for Bonnefoy, Celan and du Bouchet, among others, was: How do I regain possession of myself? Conventional narrative lyricism was out of the question and surrealism was bankrupt. Bonnefoy said that the poets’ “affective powers and our thought are too heavily marked by past events, which are so fearsomely established as givens and almost as things.” Thus annulled, the poetic would no longer proceed through familiar forms and sounds. The authority of the heroic speaker was eroded; the language would aspire upwards from the lowest of baselines and then dissipate.

In 1966, five writers gathered to launch a cultural magazine devoted to such disruptive expression. L’Éphémère was founded by Bonnefoy, Louis-René des Fôrets, Jacques Dupin, Gaëton Picon, and André du Bouchet. They were soon joined by Paul Celan (until his suicide in 1970) and Michel Leiris. Twenty issues appeared over the next seven years. As James Petterson points out, “The ephemeral, the finite, and all that fleetingly materializes in the text to destabilize a thought in the process of becoming eternal … best defines the poets of L’Éphémère.”

They shunned the pretense of having created language considered adequate to portraying a specific occasion or a given sentiment. Embracing banality, they dismissed the poem’s former role as a carrier of unique, “genuine” images. They perceived a world in which appearances and disappearances occur together, thus language should prove its fidelity to this true condition. It is, in fact, an avidity to clinch this last point that accounts for the repetition and monotony of much of their output.

Du Bouchet observed that “poetry without any padding would be poetry with big gaps – it would be riddled with gaps.” The chasms appeared not only between phrases but also on the page itself where he would specify substantial blank spaces. Below, here is part VII of the long poem “The White Motor,” translated by Auster from the collection The Uninhabited:

I am in the field

like a drop of water

on a red-hot iron

the field

eclipses itself

the stones open

like a stack of plates

held

in the arms

when evening breathes

I stay

with these cold white plates

as if I held the earth

itself

in my arms.

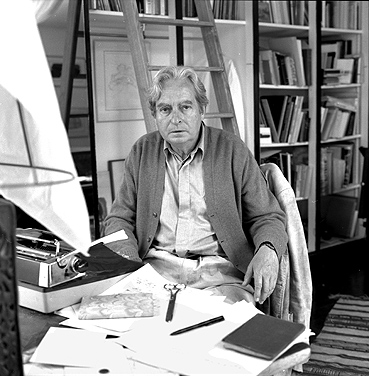

Du Bouchet’s transligualism, cultivated during his years in America, fed a lifelong commitment to translation including French versions of Shakespeare, Donne, Hopkins, Joyce, Laura Riding, Faulkner, and Hölderlin – and with Paul Celan’s collaboration, of Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva. He favored small press editions, produced several anthologies of his own work, and maintained a friendly distance from literary life. Openwork was the title of one of his anthologies. (During the years he lived with Sarah Plimpton, he turned down opportunities to record an interview with her brother’s Paris Review.)

Du Bouchet’s work, which includes prose as well as poetry, was continuously revised through the years. His notebooks often remark on the art of poetry, as in this notebook excerpt titled “The Profound Coherence …”:

The profound coherence of certain superficial, ill-assorted images, from which they clearly draw their power – while they remain muted and dull – merely reflects fidelity to outward evidence – of which often no trace is left – like a poem as soon as it stops being bound to the poet’s striving.

This coherence that makes us blindly accept a poem – as blindly as reality – and confers on both the same rudimentary nature

It could be said that in regard to this reality we have made no headway at all, and Rimbaud was no different from the others.

It’s above all in regard to the imagination that we can say we’re making headway – imagination, whether lofty or weak – also finding its echo in the real – whether exalting or repugnant

And so the most beautiful poems have led to some blank texts like a sheet of blank paper – are available: that is, they have not ceased to act. Like everything that has begun to act.

I always write to make myself worthy of the poem that is not yet written.

Without hope.

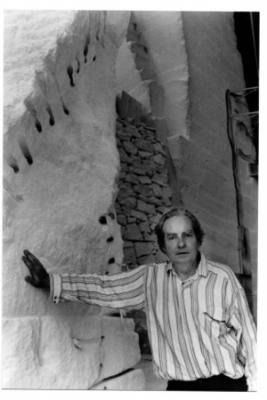

In the 1970’s, after acquiring a house in the Drôme, a picturesque and mountainous region of France where he would spent most of the next three decades, he generated several texts on art and artists, most notably on Giacometti. Rogers notes, “The author’s engagement with the visual arts would in fact lead him to represent many of his books as inner colloquies with painters and engravers, accompanied by their images.”

In the 1970’s, after acquiring a house in the Drôme, a picturesque and mountainous region of France where he would spent most of the next three decades, he generated several texts on art and artists, most notably on Giacometti. Rogers notes, “The author’s engagement with the visual arts would in fact lead him to represent many of his books as inner colloquies with painters and engravers, accompanied by their images.”

Diagnosed with leukemia in 1996, du Bouchet devoted the next five years to editing, revising, and cataloguing his work – but was disinterested in strict chronological organization. He died in 2001. For some readers, du Bouchet’s skepticism of language overpowers any other expressive effect that may be generated by language. The poet’s output, according to Du Bouchet’s peer Phillippe Lacoue-Labarthe, “is what it is only through the impossibility of bringing about what establishes its authority.” To dissolve in this instance is thus to regain the beginning point. Rogers aptly sums up du Bouchet’s achievements: “His disjunction from his language and culture had allowed him to arrive at a form of expression beyond the accidents of time and place. He had mastered a prose style that hybridized the visual and literary arts, an approach to translation that heightened its textual flexibility, and a free-floating poetry that overstepped the conventional bounds of language.”

[Published by Yale University Press on October 28, 2014. 320 pages, $26.00 hardcover. An edition in the Margellos World Republic of Letters series.]