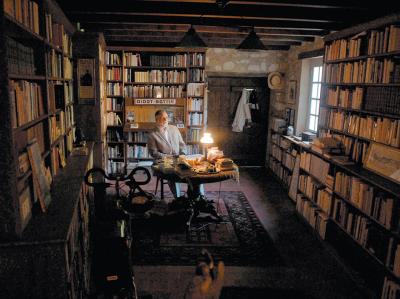

Alberto Manguel lived in Toronto for 18 years until 2000 when he shipped himself, his partner Craig Stephenson, and more than 30,000 books to a medieval stone presbytery in the southwest of France. They resided there happily for 15 years until problems “I don’t wish to recall because they belong to the realm of sordid bureaucracy” pushed them out. Friends arrived at the library he had set up in their restored barn; they packed up what had grown to 35,000 books. The world’s foremost melancholic bibliophile, Manguel was stricken by this forced departure to New York City. He writes, “If every library is autobiographical, its packing up seems to have something of a self-obituary.”

In Packing My Library Manguel is bereft of his books. He writes, “I’ve often felt that my library explained who I was, gave me a shifting self that transformed itself constantly throughout the years.” But in compensation, the loss leads to meditations on loss in his signature discursive style. “Maybe loss is an inherited trait,” he speculates. “My maternal grandmother had a gift for losing things” – and on we go to a catalog of the items she was known to have misplaced “even within the confines of her small apartment” in Buenos Aires, the city of Manguel’s birth. Grandmother speaks in memory: “’We lost our house in Russia, we lost our friends, we lost our parents. I lost my husband. I lost my language,’ she’d say in a curious mixture of Russian, Yiddish, and Spanish. ‘Losing things is not so bad because you learn to enjoy not what you have but what you remember. You should grow accustomed to loss.’”

In Packing My Library Manguel is bereft of his books. He writes, “I’ve often felt that my library explained who I was, gave me a shifting self that transformed itself constantly throughout the years.” But in compensation, the loss leads to meditations on loss in his signature discursive style. “Maybe loss is an inherited trait,” he speculates. “My maternal grandmother had a gift for losing things” – and on we go to a catalog of the items she was known to have misplaced “even within the confines of her small apartment” in Buenos Aires, the city of Manguel’s birth. Grandmother speaks in memory: “’We lost our house in Russia, we lost our friends, we lost our parents. I lost my husband. I lost my language,’ she’d say in a curious mixture of Russian, Yiddish, and Spanish. ‘Losing things is not so bad because you learn to enjoy not what you have but what you remember. You should grow accustomed to loss.’”

Packing My Library has a rocking motion, tipping back with privation, then leaning forward with appreciation. Or perhaps a better descriptor is the circular. Manguel’s essential gestures are the returning glance at his primary authors (Cervantes, Montaigne, Shakespeare, Borges, Carroll, Kafka) and the reconsideration of the printed word that lands him back exactly where he started. In The Traveler, The Tower, and the Worm (2013), he suggested that metaphors are what “language resorts to … [and] are, ultimately, a confession of language’s failure to communicate directly” but that our world “is a book we are meant to read. Its signs have a meaning, even if that meaning lies beyond our grasp.” In Packing My Library, he writes, “Faith in language is, like all true faiths, unaltered by everyday practice that contradicts its claims of power – unaltered in spite of our knowledge that whenever we try to say something, however simple, however clear-cut, only a shadow of that something travels from our conception to its utterance, and further from its utterance to its reception and understanding.”

But back to the 35,000 books, wrapped and boxed. Manguel recalls the day he began unpacking his books to set up his library in Châtellerault, beginning with a first edition of Charles Kingsley’s novel Hypatia. Packing is “an exercise in oblivion … If unpacking a library is a wild act of rebirth, packing it is a tidy entombment before the seemingly final judgment.” Another famous unpacker of books is Walter Benjamin whose essay “Unpacking My Library” (1931) states, “Thus is the existence of the collector, dialectically pulled between the poles of disorder and order.” Such is the nature of Manguel’s writing in Packing My Library. He admits that his library was governed by “a certain zany logic,” and his book reflects this disorderly orderliness. There are 11 chapters separated by 10 digressions, a game attempt to sort his impulses and notions into thematic corrals. But the horses like to break out into an open field and, of course, this is why we enjoy Manguel. When an inveterate reader recalls his library, everything expressed is digressive.

But back to the 35,000 books, wrapped and boxed. Manguel recalls the day he began unpacking his books to set up his library in Châtellerault, beginning with a first edition of Charles Kingsley’s novel Hypatia. Packing is “an exercise in oblivion … If unpacking a library is a wild act of rebirth, packing it is a tidy entombment before the seemingly final judgment.” Another famous unpacker of books is Walter Benjamin whose essay “Unpacking My Library” (1931) states, “Thus is the existence of the collector, dialectically pulled between the poles of disorder and order.” Such is the nature of Manguel’s writing in Packing My Library. He admits that his library was governed by “a certain zany logic,” and his book reflects this disorderly orderliness. There are 11 chapters separated by 10 digressions, a game attempt to sort his impulses and notions into thematic corrals. But the horses like to break out into an open field and, of course, this is why we enjoy Manguel. When an inveterate reader recalls his library, everything expressed is digressive.

After introductory remarks, he offers a chapter on misfortune, beginning with the sorrow of not having Kafka’s books within reach. Then comes a digression on revenge (perhaps he is bristling at French immigration officials) which soon comforts itself by acknowledging that Borges, for whom Manguel acted as a reader, kept only a few hundred books in his house. But then, he takes no comfort from this, and the following paragraph ensues:

“The books in my library promised me comfort, and also the possibility off enlightening conversations. They granted me, every time I took one in my hands, the memory of friendships that required no introductions, no convention al politeness, no pretense or concealed emotion. I knew, in that familiar space between the covers, that one evening I’d pull down a volume of Dr. Johnson or Voltaire I had never opened, and I would discover a line that had been waiting for me for centuries. I was certain, without having to retrace my way through it, that Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Yesterday or a volume of Cesare Pavese’s poems would be exactly what I required to put into words what I was feeling on any given morning. Books have always spoken for me, and have taught me many things long before these things came materially into my life, and the physical volumes have been for me something very much like breathing creatures that share my bed and board. This intimacy, this trust, began early on in my life.”

Early on in his life, he spent seven years in Israel where his father was Argentina’s ambassador. Then came residences in Paris, London, Tahiti and Toronto. He no sooner arrived in New York from France when “I received a message from the newly appointed minister of culture of Argentina, offering me the position of director of the National Library.” Borges himself had been appointed its director in 1955 – the fourth blind director of that institution. “After much hesitation, I accepted,” he claims. According to Stephanie Nolen’s coverage in The Globe and Mail, Manguel willingly threw himself into the muck of Argentine politics, not least by firing 400 staffers hired by his predecessor, perhaps patronage jobs. Manguel dilutes the tension by saying in Packing My Library, “I made it my priority to reorganize a number of different sections of the library so that work could become more efficient and coherent.” Earlier in the book, he claims “I’m not a seeker of novelty and excitement. I take comfort not in adventures but in routine.” This may hold for the persona who narrates his books. But apparently, the man himself has a competitive and venturesome streak.

Early on in his life, he spent seven years in Israel where his father was Argentina’s ambassador. Then came residences in Paris, London, Tahiti and Toronto. He no sooner arrived in New York from France when “I received a message from the newly appointed minister of culture of Argentina, offering me the position of director of the National Library.” Borges himself had been appointed its director in 1955 – the fourth blind director of that institution. “After much hesitation, I accepted,” he claims. According to Stephanie Nolen’s coverage in The Globe and Mail, Manguel willingly threw himself into the muck of Argentine politics, not least by firing 400 staffers hired by his predecessor, perhaps patronage jobs. Manguel dilutes the tension by saying in Packing My Library, “I made it my priority to reorganize a number of different sections of the library so that work could become more efficient and coherent.” Earlier in the book, he claims “I’m not a seeker of novelty and excitement. I take comfort not in adventures but in routine.” This may hold for the persona who narrates his books. But apparently, the man himself has a competitive and venturesome streak.

He tells us that Borges’ literary credo specified that “the writer’s task is to find the right words to name the world, knowing all the while that these words are, as words, unreachable.” Manguel cuts a charming figure as he caroms through the canon while guiding us through literary visions that are as memorable as they are phantasmal. But I wonder if all the while he has wanted most of all to be eminently reachable. If he cannot be a Dante, he can at least be our Virgil. It’s an ambitious goal – to project an unforgettable image of himself escorting us companionably “within the model of that which we attempt to reproduce in words and images.”

He tells us that Borges’ literary credo specified that “the writer’s task is to find the right words to name the world, knowing all the while that these words are, as words, unreachable.” Manguel cuts a charming figure as he caroms through the canon while guiding us through literary visions that are as memorable as they are phantasmal. But I wonder if all the while he has wanted most of all to be eminently reachable. If he cannot be a Dante, he can at least be our Virgil. It’s an ambitious goal – to project an unforgettable image of himself escorting us companionably “within the model of that which we attempt to reproduce in words and images.”

[Published by Yale University Press on March 6, 2018. 146 pages, $$23.00 hardcover]

Manguel

Wonderful review. Thank you, Ron. As one who has disbanded many personal libraries over the years – most recently in China (though none so large as Manguel’s) – I can say that it also takes a certain ruthlessness, not against the books themselves but as an occasion for critical self-reflection. Collecting does not make me who I am. Borges, blind and in charge of books, of course has always interested me. I’m not surprised he had a smallish library; I have wondered if one reason he wrote was to write that which he could not see, and thus he created his own portable library in the shelves of his mind.