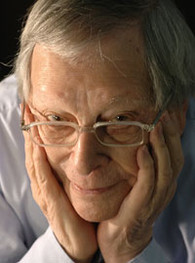

Among the last living greats of post-WWII French literature, Roger Grenier seems to have known everyone and done everything. Now at 96, he has produced perhaps his final book, Palace of Books, a collection of ten essays on writing, writers, and readers. But Grenier shows little of the summing-up impulse, no wish to memorialize his bookshelves, promulgate standards, or crown champions. His mind leaps about, making connections between works and ideas – and taking special delight in contradictions.

Forming a sub-genre unto themselves, books about reading books tend to reflect credit on their author’s perspicacity and concern for the culture. Not so with Grenier who earns the credit anyway while taking the answer to “why read?” for granted.

Published in France in 2011, each essay in Palace of Books is triggered by a looming question or nagging issue such as “Is knowing the private life of an author important?” Some topics arise from the nearness of mortality – leave-taking, suicide, books left unfinished or unread — but Grenier treats them whimsically, discursively, anecdotally, referencing a broad array of writers, mainly European.

Published in France in 2011, each essay in Palace of Books is triggered by a looming question or nagging issue such as “Is knowing the private life of an author important?” Some topics arise from the nearness of mortality – leave-taking, suicide, books left unfinished or unread — but Grenier treats them whimsically, discursively, anecdotally, referencing a broad array of writers, mainly European.

Throughout Palace of Books, Grenier pivots between the complementary and antagonistic poles of living and reading – and when he does, you can catch his tone: “One must finally come down from literary paradise and back to everyday life, where truth isn’t any truer than in books, just more difficult to bear.” This passage is from “Waiting and Eternity,” an impulsive consideration of waiting from many angles. “Waiting is what you erase from your existence,” he writes, a claim that leads to remarks on Dostoevsky and Camus:

“All Chekhov had to do was put his characters’ lines in the future tense to make them reek of despair. The creatures in his plays and short stories are the ultimate heroes of waiting. When they can’t stand it any longer, they cry out, ‘To Moscow?’ But few succeed in leaving. This is because waiting is both hope (in Spanish espera is not very different from esperanza) and resignation. In one of the essays in Nuptials, “Summer in Algiers,” Albert Camus writes: ‘From the mass of human evils swarming in Pandora’s box, the Greeks brought out hope at the very last, as the most terrible of all. I don’t know any symbol more moving. For hope, contrary to popular belief, is tantamount to resignation. And to live is not to be resigned.’”

Then, over the next five pages, he touches on Kafka, Woolf, Beckett, Blanchot, Gide, Conrad, Boccaccio, Mansfield, and even Jacques Brel. But reaching Flaubert, he takes up the stricken pleasure for those waiting in love, wanting “to believe in the beauty and in the truth of feelings that torture them.” Soon, waiting is reading itself: “One of the first acts inseparable from waiting is reading. Your eyes follow the length of a line and your mind waits for your eyes to advance, impatient to know what will happen next. But you have to be patient.” At the outset of the essay, waiting is a void, but by the end it becomes a plenitude: “Misery is when there is no more waiting possible.”

Then, over the next five pages, he touches on Kafka, Woolf, Beckett, Blanchot, Gide, Conrad, Boccaccio, Mansfield, and even Jacques Brel. But reaching Flaubert, he takes up the stricken pleasure for those waiting in love, wanting “to believe in the beauty and in the truth of feelings that torture them.” Soon, waiting is reading itself: “One of the first acts inseparable from waiting is reading. Your eyes follow the length of a line and your mind waits for your eyes to advance, impatient to know what will happen next. But you have to be patient.” At the outset of the essay, waiting is a void, but by the end it becomes a plenitude: “Misery is when there is no more waiting possible.”

Although his manner is relaxed and his perspective is broadminded, Grenier sometimes allows himself to suggest what he has learned over a lifetime. “We live our lives through the irreversible flow of time. But time consoles is about time by offering us the right to contradict ourselves,” he writes. “With time we learn; we shed our prejudices and we progress. We had to contradict ourselves quite a lot to change our way of thinking.” His leaps from one literary allusion to another embody the rich results of reading, not just because he has read so deeply, but because his readings altered him. Thus, while “time imposes narrower and narrower choices on us, ultimately irreversible … in the need to contradict ourselves, you can see a consequence of what Georges Bataille called ‘the desire to be everything.’” Taken together, title after title, the books represent everything he has tried to be.

Novelist and editor, journalist and television writer, Grenier has been writing since his coverage of France’s post-war trials in the late 1940s. During the war, he was Gaston Bachelard’s student at the Sorbonne, and later Albert Camus’ colleague and friend at Combat and France Soir. Having produced nineteen novels, over 100 short stories, biographies, and essays, he was awarded the Prix Femina in 1972 for his novel Ciné-roman and Grand Prix de Littérature de l’Académie Française in 1985. As an editor at Gallimard, he supported the work of Cortazar, Queneau, Prévert, Ionesco, Gary and many others. In North America, he is best known for a novel, The Difficulty of Being a Dog, (2000), translated by Alice Kaplan.

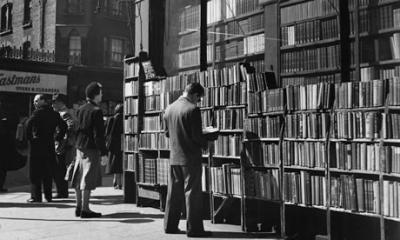

Grenier’s many delightful asides in Palace of Books tells us that in his world the books always circulated within the most lively streams of life – and without making a claim for himself, it seems he often had the inside story. “When President François Mitterand got interested in a woman,” he recalls, “he always gave her a copy of Albert Cohen’s Belle du Seigneur. I know this from the woman who worked in the bookstore where he used to stock up.”

Grenier’s many delightful asides in Palace of Books tells us that in his world the books always circulated within the most lively streams of life – and without making a claim for himself, it seems he often had the inside story. “When President François Mitterand got interested in a woman,” he recalls, “he always gave her a copy of Albert Cohen’s Belle du Seigneur. I know this from the woman who worked in the bookstore where he used to stock up.”

For all his accomplishments and clear passion for writers and literature, Greiner at the end perceives the writer’s profession at street level. “How, without blushing, can we agree to deliver to the public so many confessions and intimate motivations, even those that are disguised or dissimulated?” he asks. “That is the mystery of the quasi-religious value we assign to literature.”

[Published by University of Chicago Press on October 8, 2014. 150 pages, $20.00 hardcover]

On The Mysteries Of Value

“How, without blushing, can we agree to deliver to the public so many confessions and intimate motivations, even those that are disguised or dissimulated?”

Lord, Lord. Confess to your art. Then get the high priests off the street, and a new level back, so that the people can finally hear what’s being confessed. While I doubt that’ll do the trick, it could be a start. But wait. When books are business, and a broad taste for true literature is flagging — this slaps the disguises off, doesn’t it? Only my opinion.

Grenier

I also recommend A BOX OF PHOTOGRAPHS, also from U-Chicago Press. There you’ll find many fine stories and impressions of his life as well as his doings with his pal Brassai and figures like Weegee and Cartier-Bresson. He also writes about Camus, Degas, Schopenhaeur and Lewis Carroll and more. His “greatness” is a recent product of a long life that inhabited a great period and aided the output of writers greater than himself. But these final retrospective books are really very moving, energetic, and insightful.