Fernanda Melchor’s second novel translated into English, Paradais, opens in the middle of a complaint. Polo, a dropout working a low-level landscaping job at a high-class Mexican residential development, is tired of hearing his friend, Franco, blather about his lust for a woman and his sure-fire plans to seduce her. Franco is crude, drunk, and persistent, and Polo’s ranting is an effort to gain the moral high ground. He wants to drown Franco in contempt. But Melchor’s language suggests that Polo’s effort is akin to climbing a greased pole. Polo is as crude and drunk as his friend, and his complaints are as persistent as Franco’s braggadocio: “Ever since Señora Marian arrived on the scene something strange had been going on with fatboy: all his porn suddenly seemed shitty, grotesque, a sham; the little whores who spread their legs, the guys who fucked them …” He goes on.

You might call Melchor’s rhetorical approach the American Psycho gambit — suffuse the narrative in so much repulsiveness and grotesqueries, in so many sinuous run-on sentences, that eventually it makes a moral argument against the kind of violence the narrative is wallowing in. Whether Bret Easton Ellis successfully pulled that off is a subject of ongoing debate. With Melchor, the case is easier: This slim, angry, relentless book has a moral vision as stark and clear as its prose.

You might call Melchor’s rhetorical approach the American Psycho gambit — suffuse the narrative in so much repulsiveness and grotesqueries, in so many sinuous run-on sentences, that eventually it makes a moral argument against the kind of violence the narrative is wallowing in. Whether Bret Easton Ellis successfully pulled that off is a subject of ongoing debate. With Melchor, the case is easier: This slim, angry, relentless book has a moral vision as stark and clear as its prose.

Part of the reason why it works is because Melchor uses language not only to convey Polo’s rage — its intensity reveals how much he’s straining to conceal the sources of his anger. He references people he detests — his boss, his cousin — long before he explains the reasons why they’ve upset him. He references people he admires — his grandfather, a cousin he loves like a brother — and delays explaining the reasons for his affection and for their absence. For much of the first half of the book, language is a straightjacket for Polo; he can’t access the vocabulary for what he really wants to express. The clearest example of that, early on, is his use of they or them, pronouns without antecedents. It’s obvious soon enough that they are Narcos. But it takes some time before Polo is able to explain their role in his life. The emptiness of the pronoun — and Polo’s attempt to avoid defining it — gives the novel its tension on levels of both plot and language.

The other reason Paradais works is because it distills a theme Melchor explored powerfully in her acclaimed 2017 novel, Hurricane Season (published in English translation in 2020): the way sexual abuse of women turns into an accepted ritual, and how women are scapegoated even in the midst of their violation. In Hurricane Season, a dead woman, named the Witch, became a community’s sin eater, accused of murder, curses, and all manner of other suspect horrors.

Much the same happens in Paradais: Polo and Franco find refuge — or at least a drinking spot — in the abandoned mansion (“two stories of moldy ruin”) once owned by a woman called the Bloody Countess. “He was fully aware there was no real menace lurking inside that ruin, no pit of hungry crocodiles hidden among its grimy walls and rapacious ferns, but, man, was it hard to get the stories out of his head, the stories about the Bloody Countess that the old gossips in Progreso had told him when he was little older than a baby.” The sense of evil — and the urge to attribute it to women — has been worked into the mortar of its buildings, sunk into its soil.

The trouble with the American Psycho gambit is the moral complicity it thrusts upon the reader — any thrill we might get from it intersects with the risk that our enjoyment endorses the violence it depicts. No question, Paradais is as engrossing as it is discomfiting. Sophie Hughes’ translation gives Melchor’s candid, lurid run-on sentences a galloping pace; nothing is softened or made more graceful, but the prose is insistent and propulsive while the story accrues guns and rapes and murder. Yet (contra Ellis) the mood Melchor conjures and the trajectory of her story are both unmistakably tragic. Franco and Polo, when we meet them, are pathetic creatures, locked into hard drinking and misogyny, and early on their story is buoyed by a sense that their talk is mainly bluster. Polo, we think, might find a way out of his predicament (and away from them). In time, though, Polo’s predicament becomes increasingly horrid, both in terms of what he does with Franco and of what he finally brings himself to confess to. Language isn’t an escape, no matter how long he goes on for. “His life goal was to get the fuck out of there, earn some cash, be free, goddammit, free for once in his fucking life,” Melchor writes. His insistence is the tell that his goal is impossible.

The trouble with the American Psycho gambit is the moral complicity it thrusts upon the reader — any thrill we might get from it intersects with the risk that our enjoyment endorses the violence it depicts. No question, Paradais is as engrossing as it is discomfiting. Sophie Hughes’ translation gives Melchor’s candid, lurid run-on sentences a galloping pace; nothing is softened or made more graceful, but the prose is insistent and propulsive while the story accrues guns and rapes and murder. Yet (contra Ellis) the mood Melchor conjures and the trajectory of her story are both unmistakably tragic. Franco and Polo, when we meet them, are pathetic creatures, locked into hard drinking and misogyny, and early on their story is buoyed by a sense that their talk is mainly bluster. Polo, we think, might find a way out of his predicament (and away from them). In time, though, Polo’s predicament becomes increasingly horrid, both in terms of what he does with Franco and of what he finally brings himself to confess to. Language isn’t an escape, no matter how long he goes on for. “His life goal was to get the fuck out of there, earn some cash, be free, goddammit, free for once in his fucking life,” Melchor writes. His insistence is the tell that his goal is impossible.

In an essay in the first issue of Astra magazine, Melchor reports on the story of Evangelina Tejera Bosada, a one-time beauty queen in Melchor’s native Veracruz, Mexico, who was later convicted of inexplicably murdering her two young sons. In the years since her conviction, Melchor observes, Bosada was transformed into a figure much like the Witch in Hurricane Season, or the Bloody Countess in Paradais who snatches boys and feeds them to crocodiles in her basement. Society, rather than exploring the reasons for Bosada’s decline — beauty as a thing to be drugged, used, and disposed of — uses language as a tool to dismiss her, to turn her into a myth. She is assigned “masks that dehumanize flesh and blood women and become blank screens on which to project the desires, fears, and anxieties of a society that professes to be an enclave of tropical sensualism but deep down is profoundly conservative, classist, and misogynist.”

Polo and Franco embody this attitude in its horrid, youthful flower. Though Paradais is Polo’s story and evokes his mood, the novella is written in close third person, not first. That small bit of distance is meaningful — it suggests that Melchor isn’t interested in getting into his head so much as making an example of it. We are not meant to identify with him, just know him. He is not interesting in himself, a violent person worth exploring in his own right, a Mexican psycho. The society he’s in is what’s interesting — its brutality, its misogyny, its way of making excuses for its actions. Polo is simply its exemplar, and its consequence.

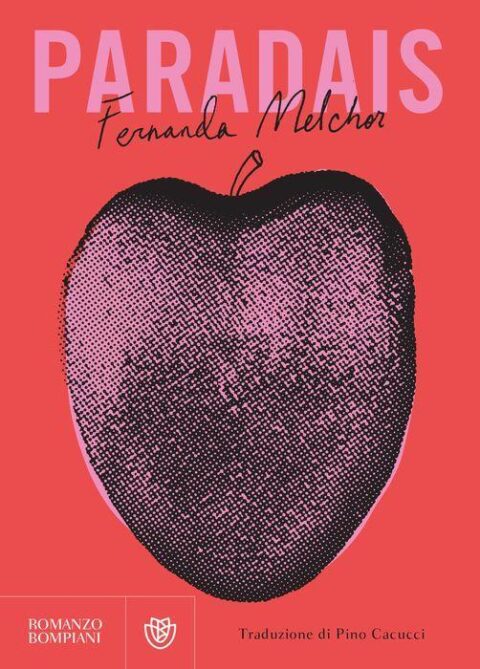

[Published by New Directions on April 26, 2022, 128 pages, $19.95 hardcover]