David Shields’ Reality Hunger: A Manifesto ardently tags after the American poets who have dismissed the facts of the day and their shotgun-riding media and arts. “Realism is a corruption of reality,” said Wallace Stevens. In 1951, as the hydrogen bomb made its debut, William Carlos Williams voiced his disregard:

“What is the use of reading the common news of the day, the tragic deaths and abuses of daily living, when for over half a lifetime we have known that they must have occurred just as they have occurred, given the conditions that cause them? There is no light in it. It is trivial fill-gap. We know the plane will crash, the train be derailed. And we know why. No one cares, no one can care. We get the news and discount it, we are quite right in doing so. It is trivial.”

“What is the use of reading the common news of the day, the tragic deaths and abuses of daily living, when for over half a lifetime we have known that they must have occurred just as they have occurred, given the conditions that cause them? There is no light in it. It is trivial fill-gap. We know the plane will crash, the train be derailed. And we know why. No one cares, no one can care. We get the news and discount it, we are quite right in doing so. It is trivial.”

Shields channels Philip Roth to make the same complaint about “American reality. It stupefies, it sickens, it infuriates, and finally it is even a kind of embarrassment to one’s own meager imagination. The actuality is continually outdoing our talents.”

Arguing for custody of the images and sounds of reality, Shields says the realists are infidels, and the clanking machinery of their novels no longer satisfies: “Living as we perforce do in a manufactured and artificial world, we year for the ‘real,’ semblances of the real. We want to pose something nonfictional against all the fabrication.” He recommends the lyric essay as antidote — and cross-genre work that blurs the imagined, the recalled, and the documented.

Arguing for custody of the images and sounds of reality, Shields says the realists are infidels, and the clanking machinery of their novels no longer satisfies: “Living as we perforce do in a manufactured and artificial world, we year for the ‘real,’ semblances of the real. We want to pose something nonfictional against all the fabrication.” He recommends the lyric essay as antidote — and cross-genre work that blurs the imagined, the recalled, and the documented.

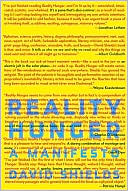

I’ll set aside his thesis for a moment – since it alone isn’t why writers should read Reality Hunger. The book comprises 618 aphoristic assertions, reflections and analyses, numbered and flowing through 26 titled chapters. Punchy and querulous, sometimes personal, the entries represent a mind sorting out its literary impulses, building confidence, and gathering energy for future projects. I find his mode and passion irresistible.

Baiting the makers of supposed verisimilitude, whether disparaging bio-pics or novels, he taunts, “Do you promise to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth? I could go on about this forever.” And he does. Here are some samples:

Baiting the makers of supposed verisimilitude, whether disparaging bio-pics or novels, he taunts, “Do you promise to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth? I could go on about this forever.” And he does. Here are some samples:

“One gets so weary watching writers’ sensations and thoughts get set into the concrete of fiction that perhaps it’s best to avoid the form as a medium of expression” (#57).

“I’ve always had a hard time writing fiction. It feels like driving a car in a clown suit. You’re going somewhere, but you’re in costume, and you’re not really fooling anybody. You’re the guy in costume, and everybody’s supposed to forget that and go along with you” (#133).

“This is the case for most novels: you have to read seven hundred pages to get the handful of insights that were the reason the book was written, and the apparatus of the novel is there as a huge, elaborate, overbuilt stage set” (#379).

“For me, anyway, the fictional construct rarely takes you deeper into the material that you want to explore. Instead, it takes you deeper into a fictional construct, into the technology of narrative, of plot, of place, of scene, of characters. In most novels I read, the narrative completely overwhelms whatever it was the writer supposedly set out to explore in the first place” (#518).

Shields expresses a similar loathing throughout for the kudzu-like growth of conventional memoir — but he qualifies his aversion: “(Ambitious) memoir isn’t fundamentally a chronicle of experience; rather, memoir is the story of consciousness contending with experience.”

Reality Hunger is less a manifesto than a pep talk, a rally where the home team psyches itself up while knowing that the opposition has an undefeated record. But since at this moment I’m very receptive to Shields’ message, initially I absorb it all – the hyperbole, indictments, and the smashing of entrenched narratives (and narrative form itself) and canons to make room for more heroic and relevant replacements. I take what I need and toss out the rest. As he cites the works of and quotes his own mentors, I jot a long list of recommended readings, from Montaigne to Elizabeth Hardwick, Pascal to Cioran. When he says “a writer serves the story without apology to competing claims” such as factual veracity, I recognize the role of the poet.

Reality Hunger is less a manifesto than a pep talk, a rally where the home team psyches itself up while knowing that the opposition has an undefeated record. But since at this moment I’m very receptive to Shields’ message, initially I absorb it all – the hyperbole, indictments, and the smashing of entrenched narratives (and narrative form itself) and canons to make room for more heroic and relevant replacements. I take what I need and toss out the rest. As he cites the works of and quotes his own mentors, I jot a long list of recommended readings, from Montaigne to Elizabeth Hardwick, Pascal to Cioran. When he says “a writer serves the story without apology to competing claims” such as factual veracity, I recognize the role of the poet.

Shields champions the lyric essay because it “tells a story at a baser level: irrational, plotless, characterless, or repetitiously characterized, it informs by serial enactments of the mind’s processes prior to writing the story.” I think of how Pessoa, des Forêts, and Jabés influence me, or how Elizabeth Hardwick, Anne Carson and Donna Stonecipher excite me – but also how a lyric essay may leave me feeling manipulated, such as Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely. Facile profundity (demanding submission to effects agreed on in advance) coagulates its gestures in any trend.

Shields castigates “most novels,” not all – and most novelists I know would concur with his criticisms of the lifeless and conventional — though they would refute his claim that the novel is incapable of generating the cerebral and profound impressions of reality that Shields feeds on.

Sometimes Shields goes so far out on the limb that he falls off. He insists that James Frey (“a horrible writer”) represents the liberation of imagination from fact, but I resist the notion. Shepard Fairey isn’t one of my culture heroes. But when Shields says the Frey affair “has to do with the culture being embarrassed at how much it wants the frame of reality and, within that frame, great drama,” I nod.

Shields touches on reality TV, modern art, stand-up comedy, documentary film. He says copyright laws are “obstructing the natural evolution of human creativity” since we all steal from each other anyway, but he also notes “the sanctity of the copy … produced the greatest flowering of human achievement the world had ever seen.” Like everyone else, Shields is confused about how writers will earn their pay in an open digital world in which “non-experts” flood the sluice.

Shields touches on reality TV, modern art, stand-up comedy, documentary film. He says copyright laws are “obstructing the natural evolution of human creativity” since we all steal from each other anyway, but he also notes “the sanctity of the copy … produced the greatest flowering of human achievement the world had ever seen.” Like everyone else, Shields is confused about how writers will earn their pay in an open digital world in which “non-experts” flood the sluice.

He tells us that he quotes without attribution throughout Reality Hunger — but the lawyers at Random House insisted that he include a list of acknowledgements. He does just that – and then asks us to ignore it, don’t look! I get the playful point. But I did look. In #474 he paraphrases Vivian Gornick: “Writing enters into us when it gives us information about ourselves we’re in need of at the time we’re reading” – thus proving I have been in need of Reality Hunger.

[Published by A.A. Knopf on February 23, 2010. 220 pages, $24.95 hardcover]

Of relevant interest —

An interview with David Shields at The Quarterly Conversation.

Ron Slate’s review of Memoir and the Art of Time by Sven Birkerts (Graywolf)

Reality Hunger

In total agreement with the artificiality of fiction.There is only one saving element—-when the feelings are real.Fiction writers too often try to get away with this, faking feelings…Poets and Playwrights cannot.That is the substantive difference in the vitality of the forms.

The Williams quotation in my

The Williams quotation in my review is almost quaint in its virtuous confidence that the “news” can be ignored as gap-fill. It’s swamping everything. Shields isn’t telling us to watch tv; he’s explaining why reality shows hold such appeal. But also, he suggests that all of us, including literature lovers, are affected by the draining of reality, and so hybrid arts, lyric essays, poetry, collage etc provide an optimum way of delivering the sense of what life feels like to us today. Novels, he says, no longer fill the need. I just reviewed Arthur Japin’s DIRECTOR’S CUT, a novel that incorporates “facts” about Fellini while imagining much else. It deeply satisfied me. But its plot-structure and characterizations are novelistic. So I’d argue with Shields about this. I also admit to having watched some segments of “Dog the Bounty Hunter” which, for all its reality pretenses, is as tightly structured as a Sunday sermon, which in effect, it is.

Shield laws

Shields really stirs it up! So, poems and plays aside (see other comment), any straightforward narratives with descriptions of, say, planes crashing into buildings or hurricanes flattening cities are gap-fills or manipulative fakes to shrug our shoulders at? I’m reminded of JS Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Tacked onto the end of a realistic story are a series of photos of a Twin Tower with a plane emerging backward from it, making it whole. Novel as flip-book. Is this solution or gimmick? Roth, realistic to the bone, predicts that in fifty years no one will be reading long-form fiction. I guess it will be all little Shieldian snippets. Don’t show his book to a novelist who has a sharp object by his desk!

On Shields

Thanks very much for your review. Coincidently, in the backyard last week, I was having a long discussion with friends about Raymond Carver and what the old term “dirty realism” meant. I think I was arguing the People-Can’t-Take-Very-Much- Reality point, although I was probably getting nowhere very fast. But if I’ve understood some of Mr Shields’ manifesto — that “The actuality [of American realism] is continually outdoing our talents” — it’s certainly infuriating when the truth is stranger than fiction: like when you tell people about actual events and they claim that you’re (just) making it up. But “his claim that the novel is incapable of generating the cerebral and profound impressions of reality”? Shields seems to be having some real fun here; it’s a limb with a big cushion under it after all. There is much bad faith (and bad writing) in the real world, true, and there is much bad faith in some certain kinds of narrative. Then, all at once, one is bewailing the power of “il vero”, the paucity of the imagination and the unlikelihood of stumbling upon “il ben trovato”? It’s good when from time to time we find that someone’s exposition rings our bells; but there is hardly a crisis in realism. Moreover, the novel is not dead — nor is it ailing. Believing it won’t make it real. Only my opinion.