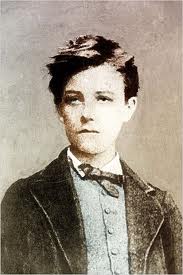

“I suspect that the chances that Rimbaud will become the bible of your life are inversely proportional to the age at which you first discover him,” wrote Daniel Mendelsohn whose balanced take on the poet may possibly be attributed to his first encountering the poems in his forties. Edmund White begins his essential biography, Rimbaud: The Double Life of a Rebel, by recollecting how he encountered Rimbaud when he was sixteen. He writes, “I identified completely with Rimbaud’s desires to be free, to be published, to be sexual, to go to Paris. All I lacked was his courage. And genius.” But later in an interview, he added, “I used to identify with Rimbaud and want to be him. Now I think he seems like a horrible brat.”

Bruce Duffy was in his fifties when he wrote Disaster Was My God (2011, Doubleday), his biographical novel about Rimbaud. Dwelling on the enigma of Rimbaud’s abandonment of poetry at the age of twenty in 1874, Duffy exerts his imagination on dramatizing events (both documented and fictional), a competent but conventional, low-stakes feat of engineering.

In light of the rational derangements of Pierre Michon’s Rimbaud the Son, I am all the more struck by the fact of his having written the book while in his forties. (Born in 1945, Michon saw the publication of Rimbaud le fils in France in 1991.) He gazes at the “aberrant ambition” of the obsessed writer, a drive both empowered and conflicted, a will to express what is foreseeable but not yet expressed that chafes against “the evidence of poetic inanity” within the writer. Michon’s language emerges from within that condition. He ventures assertive, rapt claims for literary genius while noting that “men of letters” (presumably like himself) are “futile, timid, devout.” His subject lights up his brain, stains his thought, and almost successfully evades his grip. “Alas, Rimbaud has a talent for throwing flour in the eyes of those who approach him,” he writes, “and as I say this, my arms hanging, I begin to cough; if I beat my breeches, flour comes out of them.”

In light of the rational derangements of Pierre Michon’s Rimbaud the Son, I am all the more struck by the fact of his having written the book while in his forties. (Born in 1945, Michon saw the publication of Rimbaud le fils in France in 1991.) He gazes at the “aberrant ambition” of the obsessed writer, a drive both empowered and conflicted, a will to express what is foreseeable but not yet expressed that chafes against “the evidence of poetic inanity” within the writer. Michon’s language emerges from within that condition. He ventures assertive, rapt claims for literary genius while noting that “men of letters” (presumably like himself) are “futile, timid, devout.” His subject lights up his brain, stains his thought, and almost successfully evades his grip. “Alas, Rimbaud has a talent for throwing flour in the eyes of those who approach him,” he writes, “and as I say this, my arms hanging, I begin to cough; if I beat my breeches, flour comes out of them.”

Nevertheless, Michon imposes a design his temperament allows on a meditation of Rimbaud’s four years of writing poetry, begun in 1870 before turning sixteen. His propulsive narrative spins through Rimbaud’s relationships with his mother (“all she loved in herself was the bottomless well in which everything foundered”), two non-genius poet/sponsors (Georges Izambard and Théodore de Banville), and Paul Verlaine. If the rejected mentors, Izambard (“his long life a dead letter”) and Banville, are lacking, it is because they take refuge in cultivating familiar sentiments, ill-equipped to leverage the renegade nature of language, “the little corrupted code, the meager but inexhaustible hand with which meaning is made.”

Rimbaud lived and traveled with Verlaine from the fall of 1871 until the July, 1873 when Verlaine shot him in the wrist. The carousing lovers imagined “that in seeing, ineffable, secret, postulated nebula, the most distinct poems are born, the most beautiful planetary-like systems where trees grow in twelve syllables, where the universe is embodied; embodied a second time; and regarding that second incarnation each once told himself that perhaps the other had the key.”

Rimbaud lived and traveled with Verlaine from the fall of 1871 until the July, 1873 when Verlaine shot him in the wrist. The carousing lovers imagined “that in seeing, ineffable, secret, postulated nebula, the most distinct poems are born, the most beautiful planetary-like systems where trees grow in twelve syllables, where the universe is embodied; embodied a second time; and regarding that second incarnation each once told himself that perhaps the other had the key.”

Michon’s work, too, launches from the combined fuels of humility and superfluity. He describes genius as “that almost supernatural attribute that never appears itself, overhead or in the living visible body, as halo, vigor, beauty, or youth, but that nevertheless appears in minute effects and which is confirmed in the perfection of bits of coded language more or less lengthy written in black and white. We know that these bits are generally infinitesimal. We who read them never know if they are perfect or if it was whispered to us in childhood that they were perfect, and we in turn whisper it to others, ad infinitum; and the one who writes them does not know any more than we do, if anything less, he knows it only at the moment when he joins the rods, when fitting together flawlessly like mortise and tenon they briefly exult, closing with the triumphant sound of jaws, and it is over; and when it is over once again he trembles, that is him, the poet, in those jaws, the rod has deserted him there and he no longer knows how to write …”

Michon’s work, too, launches from the combined fuels of humility and superfluity. He describes genius as “that almost supernatural attribute that never appears itself, overhead or in the living visible body, as halo, vigor, beauty, or youth, but that nevertheless appears in minute effects and which is confirmed in the perfection of bits of coded language more or less lengthy written in black and white. We know that these bits are generally infinitesimal. We who read them never know if they are perfect or if it was whispered to us in childhood that they were perfect, and we in turn whisper it to others, ad infinitum; and the one who writes them does not know any more than we do, if anything less, he knows it only at the moment when he joins the rods, when fitting together flawlessly like mortise and tenon they briefly exult, closing with the triumphant sound of jaws, and it is over; and when it is over once again he trembles, that is him, the poet, in those jaws, the rod has deserted him there and he no longer knows how to write …”

The animating notion of Rimbaud the Son is the grinding – and the rare, inexplicable meshing into art — of opposing forces in the psyche of the writer. With a few telling strokes, Michon lyrically explains how the mother “leapt wholly into the son … the old witch whom he believed he was doing in was, in the end, the one who made poetry and would do him in.” After Verlaine wounded him, Rimbaud withdrew to recuperate in his mother’s house. Michon lingers on the legacy of the parents’ “meager catechism,” the implacable, mumbling anecdote of adolescence that sounds in a poet’s ear. Rimbaud’s father, an army officer, abandoned the mother and five children when Arthur was six.

The animating notion of Rimbaud the Son is the grinding – and the rare, inexplicable meshing into art — of opposing forces in the psyche of the writer. With a few telling strokes, Michon lyrically explains how the mother “leapt wholly into the son … the old witch whom he believed he was doing in was, in the end, the one who made poetry and would do him in.” After Verlaine wounded him, Rimbaud withdrew to recuperate in his mother’s house. Michon lingers on the legacy of the parents’ “meager catechism,” the implacable, mumbling anecdote of adolescence that sounds in a poet’s ear. Rimbaud’s father, an army officer, abandoned the mother and five children when Arthur was six.

Michaud writes, “Of that I am sure: Rimbaud refused and execrated all masters, and not so much because he wanted or thought himself to be one but because his own master, that is, Carabosse’s [mother], the Captain, distant as the tsar, inconceivable as God, like them all the more sovereign for being locked away behind kremlins, behind clouds, his master had always been an ineffective phantom figure exhaled in the phantom bugles of distant garrisons, a perfect figure, beyond reach, infallible and mute, postulated, whole Realm was not of this world.”

Michaud says that Rimbaud “wanted to be poetry in person more strongly than Verlaine did,” a desire that ultimately burned itself out. Mendelsohn suggests that the shock of the shooting caused Rimbaud to realize “that deranging his and other people’s senses could have serious and irreversible consequences. Back at mom’s farm, he wrote “A Season in Hell,” “a narrative of abasement and redemption, tracing the story of a Rimbaud-like artist who has wantonly corrupted his childhood innocence.” But this is of no interest to Michon who maintains in his middle age that only a few poets have the right stuff: “the tousled ones stand for anger and nothingness, the neatly combed for salvation and charity, but they always lack the other cymbal.”

Michaud says that Rimbaud “wanted to be poetry in person more strongly than Verlaine did,” a desire that ultimately burned itself out. Mendelsohn suggests that the shock of the shooting caused Rimbaud to realize “that deranging his and other people’s senses could have serious and irreversible consequences. Back at mom’s farm, he wrote “A Season in Hell,” “a narrative of abasement and redemption, tracing the story of a Rimbaud-like artist who has wantonly corrupted his childhood innocence.” But this is of no interest to Michon who maintains in his middle age that only a few poets have the right stuff: “the tousled ones stand for anger and nothingness, the neatly combed for salvation and charity, but they always lack the other cymbal.”

Rimbaud the Son is a book about poetic expression, compulsion, freedom and failure that incorporates and emits its own obsessions. It creates the shaky ground on which one stands to take inventory of one’s accomplishments, and to prepare for the impossible. It traces the parts of others and of one’s past that inhabit the poet’s body, broken pieces that suddenly merge and break into utterance.

“Verse is an old matchmaker,” says Michon.

[Published by Yale University Press on October 22, 2013. 96 pages, $13.00 paperback.]

Yale University Press has also recently published Michon’s Masters and Servants, Winter Mythologies and Abbots.

Daniel Mendelsohn’s New Yorker essay, “Rebel Rebel: Arthur Rimbaud’s Brief Career,” may be accessed by clicking here.

Rimbaud & the French

I can attest to the fact that French teens are still reading Rimbaud’s stuff and praying to his gods. Still tres au courant. In the US we have the Beats for icons of youthful overflow, but it’s not the same thing. Jim Morrison and Bob Dylan and Patti Smith and even John Ashbery (at age 16, like the other 3) found the spark in Rimbaud. I very much like the excerpt in your piece about genius. In the US, of course, every MFA grad is a genius just as they were told in fifth grade. Zut alors!

Lone Shark, Just read …

… Frank Bidart’s METAPHYSICAL DOG or Katie Peterson’s THE ACCOUNTS or Fady Joudah’s ALIGHT or Brenda Hillman’s SEASONAL WORKS WITH LETTERS ON FIRE.

Re Rimbaud

My teacher Mme Jaccard at the Lycee in Lausanne, who many years ago introduced us to Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Rimbaud, inter alia, whose honesty and enthusiasm for their work was (I am most grateful) completely contagious, taught me to love language and its possibilities. At age 14 I remember her “explications de texte” were intoxicating. While I don’t agree with Borges’s judgement that Rimbaud was “merely a freak”, or that Baudelaide was “overrated”, and I don’t understand why he preferred Victor Hugo – as the years passed by (of course) I grew a little less impressed. She had said that Rimbaud was a perfect example of the Flying Boy, the puer, sky-bound. I wonder whether that is true, and whether his work still gives great offence to the Senex. And I wonder if we should read him today and forget his youth, to somehow imagine the speaker as another slightly cantankerous 60-year-old?

Good

pas beaucoup cassé mon enfance, et ne cherchent pas à comprendre au-delà de la romance avec Paul, sans doute l’auteur en dehors de la fiction a même moment, je ne respectais pas l’autorité qui m’a fait fslta mon père et cette nouvelle histoire de la vie se répète que l’ironie de retour à vie cette fois dans l’anonymat le plus sombre