In his 1923 treatise Ich und Du, Jewish philosopher Martin Buber argues that human existence fundamentally revolves around engagement with the world. He calls one form of relationship with the world Ich-Du — “I-You,” or more commonly “I-Thou.” An I-Thou relationship occurs when two beings meet without any objectification of each other—whether they are lovers or strangers. As opposed to an Ich-Es “(“I-It”) encounter, Ich-Du does not involve a sense of purpose, evaluation, or even analysis. It is instead a relationship of true connection, recognition, and appreciation. The encountered one need not even be aware of the encounter; what matters is that one subject relates to another subject with openness and honesty. It can also occur between humans and other living things.

In his 1923 treatise Ich und Du, Jewish philosopher Martin Buber argues that human existence fundamentally revolves around engagement with the world. He calls one form of relationship with the world Ich-Du — “I-You,” or more commonly “I-Thou.” An I-Thou relationship occurs when two beings meet without any objectification of each other—whether they are lovers or strangers. As opposed to an Ich-Es “(“I-It”) encounter, Ich-Du does not involve a sense of purpose, evaluation, or even analysis. It is instead a relationship of true connection, recognition, and appreciation. The encountered one need not even be aware of the encounter; what matters is that one subject relates to another subject with openness and honesty. It can also occur between humans and other living things.

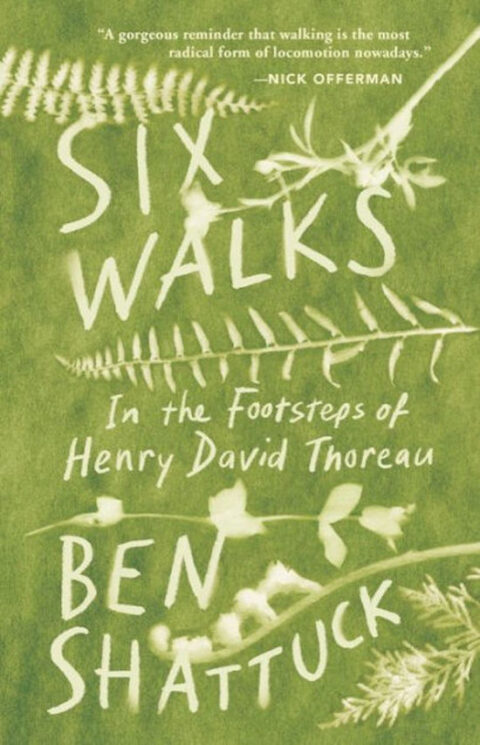

In Six Walks: In the Footsteps of Henry David Thoreau, Ben Shattuck conjures an I-Thou engagement with the Massachusetts transcendentalist. Relationships are at the heart of this gentle and moving book, a recognition the author acknowledges in his very first words where he defines “footstep” as a step made by a walker “especially as heard by another person.” Reading personal travel accounts gives Shattuck a way to hear Thoreau’s steps and points the way to follow after him.

He decides to start this walking project as a way to experience the peace and restoration that may be inspired by encounters with the natural world. Hoping to escape the “doubt, fear, shame, and sadness that had arranged a constellation of grief” around him after a breakup, Shattuck first retraces Thoreau’s journey along the beaches of southeastern Massachusetts. Before setting off, he fills his backpack with a rain jacket, snacks, and a copy of Thoreau’s Cape Cod to keep him company. To paraphrase Omar Khayyam, he brings a loaf of bread, a brick of cheese—and Thou.

Shattuck may never invoke Buber, but his way of regarding Thoreau — as a silent companion, a double, a person worthy of not only appreciation but interrogation — resonates as an I-Thou encounter. So do those with the people he meets on this walk and the paths that follow. One couple offers him a room for the night when the temperatures drop too low to sleep outside. The husband and wife feed him and share memories of their youth on the Cape. Shattuck’s evening with them reminds him that “no matter how crowded our lives feel, the old ways haven’t entirely disappeared. You can still reach back” to times similar to the ones that Thoreau himself might have felt, including “the satisfaction of a warm house on a winter day.”

Shattuck may never invoke Buber, but his way of regarding Thoreau — as a silent companion, a double, a person worthy of not only appreciation but interrogation — resonates as an I-Thou encounter. So do those with the people he meets on this walk and the paths that follow. One couple offers him a room for the night when the temperatures drop too low to sleep outside. The husband and wife feed him and share memories of their youth on the Cape. Shattuck’s evening with them reminds him that “no matter how crowded our lives feel, the old ways haven’t entirely disappeared. You can still reach back” to times similar to the ones that Thoreau himself might have felt, including “the satisfaction of a warm house on a winter day.”

Shattuck’s interest in forming connections with the world extends to urban and modern adventures as well. After another long day of walking on the beach, he heads into a pub to fill his rumbling belly with freshly-caught seafood. An elderly lady sitting beside him strikes up a conversation, and he responds. “If I’ve learned anything from novels,” he explains to the reader, “it’s that you talk to a stranger at the bar when they talk to you.” After the woman throws back a few too many cocktails, she requests that Shattuck escort her home. He becomes her companion in those moments, dropping her off at her door and recognizing not only her quirky drunkenness but their shared humanity.

During his trip to Wachusett Mountain, Shattuck rests on a grassy slope to peer at the night sky. Since he does not know the names of constellations as Thoreau did, he pulls out his phone and downloads an app. He lifts his phone to the sky to see Cygnus, the Swan — and tentatively suggests that this moment feels sacred. He writes:

“Henry had walked to Wachusett, sat up on the summit and looked at the stars as if they were ‘given for a consolation’ six months after his brother died. Was he doing the same thing I was doing? Walking to husk the dead skin of grief? Looking up to feel the comfort of one’s own smallness in the world, to displace bulging selfhood, under the shadow of such urgent beauty as they night sky? To force loss or confusion microscopic in perspective?”

In the second half of the book, the narrative leaps to a moment years after his night on Wachusett Mountain. Now Shattuck no longer travels to avert loneliness. Instead, he acquires a jug of wine and a loaf of bread to share with a companion, his new Thou. He packs a picnic basket before they set off. Before he closes the lid, he nestles inside it a box he has carved from the limb of an oak tree in his backyard. It contains his great-grandmother’s ring, to be offered to his beloved.

During one of Shattuck’s last walks, a trip with an old friend up in the Maine Woods, he thinks of Thoreau’s account of finding a piece of phosphorescent wood with light emanating from the sapwood directly under the bark. After discovering it, Thoreau cut several small chips from the glowing limb and was awed that “they lit up the inside of my hand, revealing the lines and wrinkles,” as he wrote. “It could hardly have thrilled me more if it had taken the form of letters, or of the human face.” Shattuck sees in Thoreau’s words both “metaphor and meaning”: as he sees it, “a man carrying back to camp illuminated wood is, in a way, the heart of his work.”

Extraordinary encounters like these seem like promises that Shattuck celebrates without reservation. Far less extraordinary moments also open him to the world, too. When he sees an enormous frog, larger than any he had ever seen, Shattuck wonders if the frog is looking at him as well — not just as a human interloper “but as an individual,” recognizing him in some sense as a trustworthy companion. Eventually, he comes to understand his own quest in a new way: “Maybe what I want when I go out in nature is not to see it,” he writes, “but to be seen by it. To receive anointment.”

Extraordinary encounters like these seem like promises that Shattuck celebrates without reservation. Far less extraordinary moments also open him to the world, too. When he sees an enormous frog, larger than any he had ever seen, Shattuck wonders if the frog is looking at him as well — not just as a human interloper “but as an individual,” recognizing him in some sense as a trustworthy companion. Eventually, he comes to understand his own quest in a new way: “Maybe what I want when I go out in nature is not to see it,” he writes, “but to be seen by it. To receive anointment.”

Finally, Shattuck confronts Buber’s ideal Thou, or at least its modern version — “the spirituality of a life.” Experiences in nature, he explains, teach us to recognize that what we see when we look overhead on a starry night is the same sky we see on a sunny afternoon at the beach. “Grief and joy are in the same life,” he says as he expands the metaphor. “It is one canopy of light spread over your whole life’s landscape.”

Six Walks is at its heart a meditation on love — romantic love for a partner, lasting relationships with close friends, and all the deep connections we make with the natural world. For contemplative readers, this may be the perfect beach read.

[Published by Tin House on April 19, 2022, 280 pages, $22.95 hardcover]