In 1980, Sarah Charlesworth hung seven large photographic prints in Tony Shafrazi’s living room, his first gallery. The 78-inch high prints depicted bodies falling from fatal heights. She had collected photographs from newspapers and wire services, then magnified, re-shot, and cropped them into grainy free-falls. This was one mark of the advent of the Pictures Generation, those artists who took aim at the visual language of mass media.

Seven additional negatives were produced for this series titled Stills, but they were not printed until 2012 when Charlesworth’s artist’s proofs were made available to the Art Institute of Chicago. All 14 images have finally been published as Stills, along with an essay by Matthew Witkovsky, an AIC curator. “These greatly enlarged prints could be seen as restoring the fallen subjects they depicted, metaphorically standing them up again,” he writes, “or, in a less redemptive mode, allowing viewers to imagine themselves stepping into the picture. At this tremendous scale, Stills suggested an equivalence between viewer and subject that is key to the emotional impact of each piece.”

Seven additional negatives were produced for this series titled Stills, but they were not printed until 2012 when Charlesworth’s artist’s proofs were made available to the Art Institute of Chicago. All 14 images have finally been published as Stills, along with an essay by Matthew Witkovsky, an AIC curator. “These greatly enlarged prints could be seen as restoring the fallen subjects they depicted, metaphorically standing them up again,” he writes, “or, in a less redemptive mode, allowing viewers to imagine themselves stepping into the picture. At this tremendous scale, Stills suggested an equivalence between viewer and subject that is key to the emotional impact of each piece.”

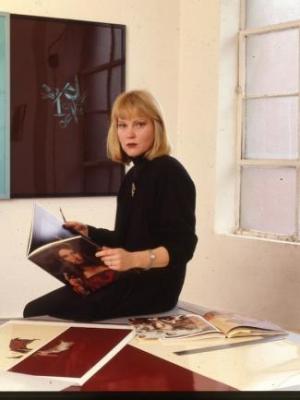

In 2013, a few months after making the new set of prints, Charlesworth died suddenly from a brain aneurysm at age 66. If she had not been as well known as Cindy Sherman and Louise Lawler, her Pictures Generation peers, perhaps this is because Charlesworth was a more restive artist who forswore past accomplishments for new approaches. Although the variations of her techniques precluded a more marketable signature style, everything she made was readily identifiable as her own.

In 2013, a few months after making the new set of prints, Charlesworth died suddenly from a brain aneurysm at age 66. If she had not been as well known as Cindy Sherman and Louise Lawler, her Pictures Generation peers, perhaps this is because Charlesworth was a more restive artist who forswore past accomplishments for new approaches. Although the variations of her techniques precluded a more marketable signature style, everything she made was readily identifiable as her own.

In 1975, Charlesworth and fellow artists launched The Fox, an influential but short-lived art magazine with a belligerent Marxist bias. (The editors attacked each other and the magazine closed after three issues.) The premiere issue featured Charlesworth’s manifesto, “A Declaration of Dependence,” in which she stated, “We have lost touch – not only with ourselves and with each other but with the culture of which we are a part. It is only by confronting the problem of our alienation, making this the subject of our work, that our ideals take on new meaning.”

The “Declaration” is passionate and articulate – but the epigraph she chose for it is more concise in its qualms. She quoted Stanley Diamond: “Highly bureaucratic states … exert, both internally and externally, a steady pressure, reducing culture to a series of technical functions. Put another way, culture, the creation of shared meanings, symbolic interaction, is dissolving into a mere mechanism guided by signals.” Charlesworth had taken up the cause of predecessors like Bertolt Brecht, a critic of artists who “thinking that they are in possession of an apparatus that in reality possesses them, they defend an apparatus over which they no longer have any control.”

The “Declaration” is passionate and articulate – but the epigraph she chose for it is more concise in its qualms. She quoted Stanley Diamond: “Highly bureaucratic states … exert, both internally and externally, a steady pressure, reducing culture to a series of technical functions. Put another way, culture, the creation of shared meanings, symbolic interaction, is dissolving into a mere mechanism guided by signals.” Charlesworth had taken up the cause of predecessors like Bertolt Brecht, a critic of artists who “thinking that they are in possession of an apparatus that in reality possesses them, they defend an apparatus over which they no longer have any control.”

For this reason, Charlesworth didn’t believe she was in the business of advancing the medium called photography for the glory of the medium or the artist. She didn’t call herself a photographer. She told a Bomb magazine columnist in 1990, “I’ve engaged in questions regarding photography’s role in culture for 12 years now, but it is an engagement with a problem rather than a medium.” The problem was explained for the public by Susan Sontag – images are becoming dictatorial mediators of what we know of experience. But Rainer Maria Rilke spelled it out in 1923 in the Duino Elegies:

More than ever

things fall away, parts of experience, for

what replaces, crowds them out, is acting without an image.

Unrevealed as themselves, the controlling forces exploit images in the culture to mold response. Charlesworth worked to take them back and encourage wilder reactions.

The story goes that when Charlesworth traveled to China in 1978, she gave up on Marxism after witnessing widespread poverty in the countryside and dour conformity in the cities. Political theory may have offered an armature for her thinking, but ultimately the images had to stand alone – and reflect something of the artist. “There is always a social pole,” she remarked in a 1988 interview. “But by my process of isolating [the images], setting them in a specific formal context, my personality enters into it.”

Witkovsky notes, “Public and personal histories, or individual and collective encounters with fate, are intertwined in these photographs.” The public history of September 11, 2001 immediately intrudes; Charlesworth recognized the inevitability of her images’ evocation of and connection to the plummeting bodies from the World Trade Center. Despite Charlesworth’s re-use of media imagery to deflate media’s power, our reaction to her prints may hardly vary from how we view the 9/11 photos. In the moment of making them, her prints demanded an avant garde status. Now they may seem merely exploitative.

Her ex-husband, the filmmaker Amos Poe, said of her, “She believed that aesthetics was morality. She lived her life that way.” But Charlesworth’s art never suggested that she was a morally pristine victim, a stance now metastasizing ever more rapidly in American arts and letters. She did not produce art that demands one’s acquiescence in advance and credit for the creator. Her critics point out that Andy Warhol executed the falling-persons imagery before her — and that Aaron Siskind’s series “The Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation” (1953) glories in the shapes of tumbling bodies but without playing on our receptivity to horror.

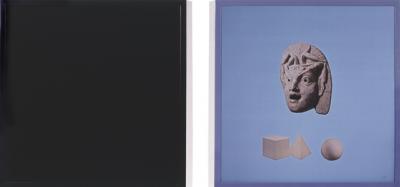

In the late 1980’s, Charlesworth began photographing her own objects, often setting them on matching colored backgrounds and frames, some somber, some sly and biting in critique. One of my favorite pieces is titled “Fear of Nothing.” A diptych, the work features a panel on the right comprising a classical facial sculpture and three elemental cut-outs as if pasted on a blue background, juxtaposed with a black rectangle of the same size on the left. Does she mean: “This is my rendition of abject fear of nothingness”? Or is she encouraging us: “We can stare at the blank space and fear nothing.” By way of commenting, she left us on our own: “What I’m doing is letting whatever power, whatever affect they have, work on its own.”

In the late 1980’s, Charlesworth began photographing her own objects, often setting them on matching colored backgrounds and frames, some somber, some sly and biting in critique. One of my favorite pieces is titled “Fear of Nothing.” A diptych, the work features a panel on the right comprising a classical facial sculpture and three elemental cut-outs as if pasted on a blue background, juxtaposed with a black rectangle of the same size on the left. Does she mean: “This is my rendition of abject fear of nothingness”? Or is she encouraging us: “We can stare at the blank space and fear nothing.” By way of commenting, she left us on our own: “What I’m doing is letting whatever power, whatever affect they have, work on its own.”

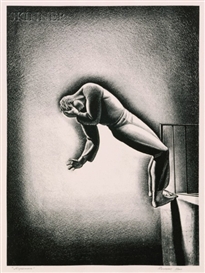

David Mamet once remarked, “It is the immemorial dream of the talentless that a sufficient devotion to doctrine will produce art.” Charlesworth welcomed the thrall of doctrine – but her impulses ultimately superseded it, even while preserving her social values. She permitted her style to thrive and evolve by privileging her instincts. In 1940, Rockwell Kent produced a pen and ink drawing called “Nightmare” (left) – an image that anticipates and rivals – and perhaps exceeds in force through sheer intentionality — the newspaper photographers’s shot of a falling body. Charlesworth’s images, too, congregate with our communal sense of falling through time, and the individual’s dizzy sense of tumbling through turmoil.

David Mamet once remarked, “It is the immemorial dream of the talentless that a sufficient devotion to doctrine will produce art.” Charlesworth welcomed the thrall of doctrine – but her impulses ultimately superseded it, even while preserving her social values. She permitted her style to thrive and evolve by privileging her instincts. In 1940, Rockwell Kent produced a pen and ink drawing called “Nightmare” (left) – an image that anticipates and rivals – and perhaps exceeds in force through sheer intentionality — the newspaper photographers’s shot of a falling body. Charlesworth’s images, too, congregate with our communal sense of falling through time, and the individual’s dizzy sense of tumbling through turmoil.

[Published by the Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press on October 21, 2014. 64 pages, 8 color and 18 b/w illustrations, $25.00 hardcover]

Shown above:

Plate 1: “Unidentified Man, Ontani Hotel, Los Angeles”

Plate 2: “Patricia Cawlings, Los Angeles”

Plate 3: “Fear of Nothing” (1987)

Plate 4: “Nightmare” by Rockwell Kent

On Falling

Thank you for yet another thoughtful review. Just a few rambling thoughts. (I admit, having myself taken a near fatal fall, that Charlesworth’s photos of falling bodies are disturbing! I wish none of it for anyone of course, but the Oh Shit moment lasts a long time afterwards.) Her piece, “Fear of Nothing” looks to me like a break from that experience. Nothingness isn’t the same as the abyss. Something that jumpers (or fallers) quickly discover.That all the things of this life fall away is a given. It’s a moderating aesthetic, maybe even a moral position of its own. You sort it out. Maybe you make giant prints. This is marvellously serious work and statement by Charlesworth, but I wonder whether today’s post Sept. 11 morality would wish to hobble some of her images. Whether one considers oneself an artist or not, “the dictatorial mediators of what we know of experience” suggests that the equivalence of viewer and subject rattles the prison bars of a critic’s eye.