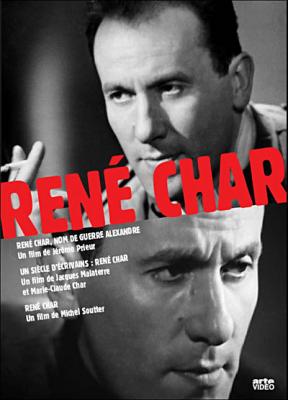

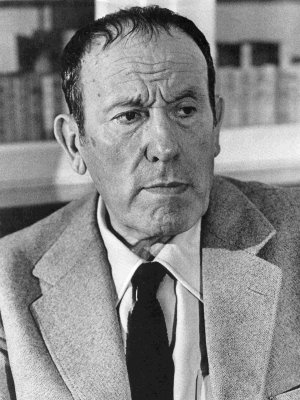

When René Char died in 1988 at the age of 80, President Jacques Chirac called him “the greatest French poet of the twentieth century.” The writer Françoise Giraud remarked that Chirac “would read poetry behind a copy of Playboy” presumably to preserve his reputation as a seducer, but it’s more likely that Chirac encouraged the anecdote. In any case, perhaps he envied Char’s complex identity as a wartime patriot, man of action, public figure – and a charismatic maker of famous verse.

In 1942 Char assumed leadership of the Céreste maquis, an underground unit operating in the south of France. His code name was “Hypnos,” the Greek god of sleep. One of his many aphorisms reads, “The poet must keep an equal balance between the physical world of waking and the dreadful ease of sleep; these are the lines of knowledge between which he lays the subtle body of the poem, moving indistinctly from one to the other of these different states of life.” When most alert to the world, he was preoccupied with the daily details of his command. Sleeping, he was entirely vulnerable. It seems both remarkable and no coincidence in his case that Leaves of Hypnos (Feuillets d’Hypnos [1946]), his wartime notebook (translated by Cid Corman), contains some of his most penetrating writing about poetry.

In 1942 Char assumed leadership of the Céreste maquis, an underground unit operating in the south of France. His code name was “Hypnos,” the Greek god of sleep. One of his many aphorisms reads, “The poet must keep an equal balance between the physical world of waking and the dreadful ease of sleep; these are the lines of knowledge between which he lays the subtle body of the poem, moving indistinctly from one to the other of these different states of life.” When most alert to the world, he was preoccupied with the daily details of his command. Sleeping, he was entirely vulnerable. It seems both remarkable and no coincidence in his case that Leaves of Hypnos (Feuillets d’Hypnos [1946]), his wartime notebook (translated by Cid Corman), contains some of his most penetrating writing about poetry.

It is as if the partisan fighter was wholly given to tracking and affecting events, while the sleeper represented inert, self-wrapped monotony – but between them, intermittently, flared the life of the poet. “Magician of insecurity,” says Char, “the poet has nothing but adopted satisfactions.” The patriot would have his way, exert power, take control – but the poet speaks forever out of irreconciliation with the world. The poem is “inseparable from the foreseeable, but not yet formulated.” The patriot imposes; the poet reveals.

In “Cotes” (“Assessment”) he writes, “A few beings are neither in society nor in a state of dreaming. They belong to an isolated fate, to an unknown hope. Their open acts seem anterior to time’s first inculpation and to the skies’ unconcern. It occurs to no one to employ them. The future melts before their gaze. They are the noblest and the most disquieting” (translated by Mary Ann Caws). The patriot uses words that have already been spoken, phrases that repeat his ethos, orders to perform practiced acts. But the poet speaks “to an insolated fate, an unknown hope.”

In “Cotes” (“Assessment”) he writes, “A few beings are neither in society nor in a state of dreaming. They belong to an isolated fate, to an unknown hope. Their open acts seem anterior to time’s first inculpation and to the skies’ unconcern. It occurs to no one to employ them. The future melts before their gaze. They are the noblest and the most disquieting” (translated by Mary Ann Caws). The patriot uses words that have already been spoken, phrases that repeat his ethos, orders to perform practiced acts. But the poet speaks “to an insolated fate, an unknown hope.”

Char exemplifies the poet whose writing cannot exist unless he exerts himself in the world and then flees from it into “easeful sleep.” Although his personal history makes him a unique figure, he always encouraged people to disregard it when considering his poems. He said, “The poem is furious ascension; poetry, the game of arid riverbanks. I am a man of riverbanks – excavation and inflammation – not always able to be torrent.” Knowing his situation and married to it, he was determined that his poems should call out only to their own designs.

NOT ETERNAL NOR TEMPORAL

O wheat in May, green in the shivering earth that has never known sweat. A happy distance from diving suns of the ends of lives. Low-lying under the long night. Color glows, watered. For vigil and last rites, two bedside blades: the skylark, bird who alights, and the crow, the spirit engraving itself.

The translation above is one of forty-eight included in Nancy Naomi Carlson’s Stone Lyre: Poems of René Char. In a foreword, Ilya Kaminsky notes this collection’s featuring of “the poet’s stylistic unity over the years – the intensity, the dream-like language, the gravity of tone, and the constant impression that one is reading not words in a language but sparks of flames that defy any attempt at interpretation, or rather that open themselves to multiple interpretations at once.” But Char’s work doesn’t defy interpretation, since the poems were not written in such opposition, as if they were fortified castles inviting invaders to die at their walls. Interpretation is simply not one of Char’s concerns. Yet one cannot read the final sentence of “Not Eternal Nor Temporal” and fail to be stunned by what it says, almost unspeakably except in these owned images, about his life and his art.

The translation above is one of forty-eight included in Nancy Naomi Carlson’s Stone Lyre: Poems of René Char. In a foreword, Ilya Kaminsky notes this collection’s featuring of “the poet’s stylistic unity over the years – the intensity, the dream-like language, the gravity of tone, and the constant impression that one is reading not words in a language but sparks of flames that defy any attempt at interpretation, or rather that open themselves to multiple interpretations at once.” But Char’s work doesn’t defy interpretation, since the poems were not written in such opposition, as if they were fortified castles inviting invaders to die at their walls. Interpretation is simply not one of Char’s concerns. Yet one cannot read the final sentence of “Not Eternal Nor Temporal” and fail to be stunned by what it says, almost unspeakably except in these owned images, about his life and his art.

Carlson’s versions are finely attuned to Char’s euphony. Below, her translation of “Secret Love”:

L’AMOUREUSE EN SECRET

Elle a mis le couvert et mené à la perfection ce à quoi son amour assis en face d’elle parlera bas tout à l’heure, en la dévisageant. Cette nourriture semblable à l’anche d’un hautbois.

Sous la table, ses chevilles nues caressent à présent la chaleur du bien-aimé, tandis que des voix qu’elle n’entend pas la complimentent. Le rayon de la lampe emmêle, tisse sa distraction sensuelle.

Un lit, très loin, sait-elle, patiente et tremble dan l’exil des draps odorants, comme un lac de montagne qui ne sera jamais abandonné.

***

SECRET LOVE

She has set the table, refined what her love, seated across, will speak softly of, looking deeply into her eyes. Food like an oboe’s reed.

Under the table’s cover now, her bare ankles stroke her lover’s warmth, while voices she does not hear sing her praises. The lamp’s stream of light tangles, weaves voluptuous daydreams.

She knows a bed – far, far away – waits patiently, trembling in exile of sheets fragrant with musk, like a mountain lake that will never be forsaken.

I’ve admired Mary Ann Caws’ translations since they first appeared in 1976. While Carlson takes more liberties, she also makes Char’s work sound more spoken or lyrical in many spots. For instance, where Caws ends “Secret Love” with “like a mountain lake never to be abandoned,” a literal transfer, Carlson writes “like a mountain lake that will never be forsaken,” a gesture that resonates beautifully with the implied emotions of the poem’s characters. There are several other enhancements by Carlson in this one poem alone, and she translates a dozen others included in Caws’ volume. So, if you want to get acquainted with Char’s poetry, I suggest you start with Stone Lyre.

I’ve admired Mary Ann Caws’ translations since they first appeared in 1976. While Carlson takes more liberties, she also makes Char’s work sound more spoken or lyrical in many spots. For instance, where Caws ends “Secret Love” with “like a mountain lake never to be abandoned,” a literal transfer, Carlson writes “like a mountain lake that will never be forsaken,” a gesture that resonates beautifully with the implied emotions of the poem’s characters. There are several other enhancements by Carlson in this one poem alone, and she translates a dozen others included in Caws’ volume. So, if you want to get acquainted with Char’s poetry, I suggest you start with Stone Lyre.

In René Char’s poetry, Maurice Blanchot heard “the enjoyment of what has not been granted.” He quotes the poet from The Formal Share (Alone They Remain): “Imagination consists in expelling from reality many incomplete persons, making use of the magical and subversive powers of desire, to obtain their return in the form of a completely satisfying presence. This, then, is the inextinguishable, uncreated reality.” These two numinous sentences describe not only Char’s tortuous dynamic, but also that of every great poet, freedom fighter or otherwise.

[Published by Tupelo Press on January 1, 2010. 96 pages, $16.95 paperback.]

Char’s many translators

It may be worth mentioning that Rene Char has had many translators and that there’s a much wider choice out there than just between Caws and Carlson. For example, William Carlos Williams, Samuel Beckett, WS Merwin, James Wright, Kenneth Rexroth, Thomas Merton, Richard Wilbur, and Gustaf Sobin.

your review of Nancy’s trans. of Char

Beautifully written, Ron.