“One day in late autumn 2006, I took a flight from London to Mexico City, a piece of paper with a telephone number on it in my pocket.” So begins, prosaically enough, Joanna Moorhead’s new biography, Surreal Spaces: The Life and Art of Leonora Carrington, her second book about her distant cousin, the surrealist artist and writer. It’s a thoroughly illustrated, standalone work that follows Moorhead’s 2017 biography The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington. The new work opens with Moorhead meeting her famous (in Mexico) and infamous (to her remaining family in England) relative, a woman she has already written one biography about. Which begs the question, why two books by one author covering the life of a single artist?

One answer might be that even by 20th century standards, Carrington’s life was geographically, artistically and romantically effusive, spanning continents and wars, romantic and artistic entanglements, and a profusion of creative formats, from easel painting to novels, with plenty of variety in between. That Carrington lived and worked through it all is a story well worth following; that she survived any one of the many obstacles in her becoming a world-recognized artist – from a sheltered Catholic childhood in England, to Nazi occupation in France, from motherhood to immigration – is nearly miraculous; that she lived to an advanced age, making art and writing until the end, is testament to her singular will.

One answer might be that even by 20th century standards, Carrington’s life was geographically, artistically and romantically effusive, spanning continents and wars, romantic and artistic entanglements, and a profusion of creative formats, from easel painting to novels, with plenty of variety in between. That Carrington lived and worked through it all is a story well worth following; that she survived any one of the many obstacles in her becoming a world-recognized artist – from a sheltered Catholic childhood in England, to Nazi occupation in France, from motherhood to immigration – is nearly miraculous; that she lived to an advanced age, making art and writing until the end, is testament to her singular will.

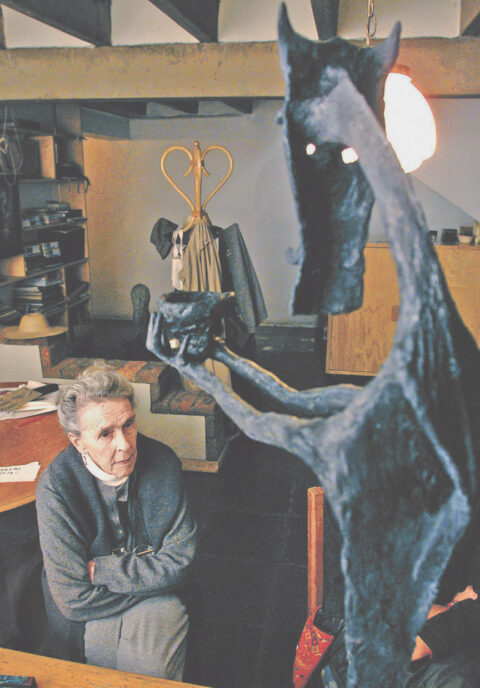

In Surreal Spaces, Moorhead traces Carrington’s will in the world via the places she inhabited and those that formed her – homes in Britain, France, America, Mexico and more – and where Carrington created visual art, short and long fiction, and a trenchant memoir. Moorhead met Carrington when the latter was in her late eighties, living in Mexico, far from her place of birth. Since Moorhead was a journalist and also family, however distant, served her well as an interviewer, since her wary cousin “had little time for art historians.” Moorhead’s profession also means she’s perhaps more interested in Carrington’s life story than in the art itself, though the concept of “surreal spaces” might nicely serve both. It’s a compelling conceit, not least because, as Carrington herself wrote in her novel, The Hearing Trumpet, “Houses are really bodies.” It’s an idea all the more true for women, whose lives are so often intertwined with the home. See, for example, Louise Bourgeois’s many iterations of her “Femme Maison,” featuring female nudes with houses for heads.

Extensively illustrated, with photographs of Carrington’s world and the people in it, as well as reproductions of her artwork, Moorhead’s biography draws specific connections between Carrington’s life and art. This choice is sometimes illuminating, but it’s also potentially problematic, as writing on women artists is often criticized for being too tethered to their biographies. Especially artists like Carrington, whose May-December relationship with fellow artist Max Ernst mirrors that of other female modernist pioneers like Georgia O’Keeffe (Alfred Stieglitz) and Frida Kahlo (Diego Rivera).

And yet, the awesome arc of Carrington’s life is irresistible. Raised Catholic in England to an Irish mother and wealthy English industrialist father, Carrington was kicked out of Catholic school at 15, then attended finishing school in Florence, which abetted her artistic ambitions more than her feminine ones. Of Carrington’s time in Italy, Moorhouse writes, “Her notes on Michelangelo are particularly interesting: ‘He always desired to be an artist, but his father opposed him.’” Carrington’s own father opposed her desires, naturally, but conveniently sent his daughter to a second finishing school in Paris when she couldn’t return to Florence after a bout of appendicitis. Opportunity for a budding artist was everywhere, even in illness.

Leonora Carrington, “Bird Bath II,” 1978. Acrylic on canvas board. Private collection. Courtesy Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco

At 17, she returned to England where she was expected to land a marriage that might secure her rich-but-working-class family some social imprimatur. By spring 1935, Carrington was a reluctant debutante in London high society. She was also a quiet rebel, reading Aldous Huxley’s Eyeless in Gaza at Ascot rather than seeing and being seen. From there, her rebellion bloomed. After visiting the International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936, she somehow convinced her reluctant parents to let her study art in London. The following year she met one of those exhibiting surrealists, the German artist Max Ernst, and soon ran away with him and a coterie of other avant-garde artists to the British countryside. A famous (even infamous) photograph taken there by Lee Miller shows a barely 20-year old Carrington nude from the waist up, with Ernst’s heavily veined 46-year old hands covering her otherwise bare breasts. Whether you find all of that delightful or icky, it’s certainly fun to read about.

Moorhead’s stance outside the art history discipline served her well when her subject was alive, but it may be a little glancing for the reader. Fort instance, she doesn’t bother to define or grapple with surrealism as a movement. On the other hand, Carrington was no card-carrying member of the group, nor was she any kind of theorist, nor even much taken with theories about the meaning of her work. As she told the New York Times in 2003, “I am as mysterious to myself as I am mysterious to others.”

That mystery extended to her work, where Carrington didn’t like digging into the symbolic meaning of what she painted. According to Moorhead, “She believed that art spoke to people in the deepest part of their psyche. She warned me not to try to rationalize or intellectualize it … ‘You’re trying to intellectualize something desperately, and you’re wasting your time. That’s not a way of understanding.’”

But ironically, Moorhead’s account is most interesting in revealing the clear correspondences between Carrington’s work and the places she lived. Discovering, for example, that Carrington grew up in a “turreted Gothic mansion,” with the Dickension (or maybe Rowlingesque) name Crookhey Hall, is an amusingly spot-on launching pad for a surrealist career. And when Moorhead divines rooms and figures and features of the property that also furnish Carrington’s canvases, the discovery is delightful. Rather than draining Carrington’s artwork of magic, the connections offer the electricity – and mystery – of lived experience and of memory.

Those connections feel looser as Carrington’s story unspools, first to Paris and then a fairytale-like time in the French countryside with her lover, Ernst. Their artistic idyll ends abruptly when Nazis invade and Ernst, a German citizen who had fled Nazi rule, is imprisoned. Carrington escapes France without him, where a marriage of convenience in Portugal gets her to New York, then onto Mexico where she divorces that husband and in 1946 marries Emerico “Chiki” Weisz, a Jewish-Hungarian photographer who evaded the Nazis and made a life with Carrington in Mexico City. They were married for over 60 years, raised two sons, and Carrington died there in 2011 at the age of 94. A surreal life in some respects, but in others, a rather unexpectedly prosaic one.

In her 1944 memoir, Down Below, Carrington wrote of “the hostility of Conformism.” That an artist’s non-conformity might ultimately lead to long talks in a warm kitchen, sharing tea between distant cousins who meet across generations and continents, is an idea both cozy and sort of surreal. As recounted by Moorhead, it’s a domestic scene that charmingly captures the singular life of Leonora Carrington.

[Published by Princeton University Press on August 22, 2023, 224 pages, $38.00 US hardcover.