The X feed Liminal Spaces, as its name suggests, is populated with photos of uncertain in-between areas: hallways, anterooms, lobbies, foyers, stairwells, waiting areas. Places between here and there; spaces that aren’t designed for extended stays. Places where you don’t want to linger. There’s no official rule that liminality demands weak, horror-movie lighting, but windowless, fluorescent-lit spaces dominate, underscoring the queasy, David Lynchian uncertainty that the feed tries to cultivate.

At Liminal Spaces — unlike most actual liminal spaces — people tend to be absent, which further intensifies the queasy feeling. People would spoil the mood. When people are absent, we see how absurd these spaces are, geometrically peculiar and single-use. I think the absence is also a way of suggesting that we ourselves are liminal — neither here nor there, forever in process and uncertain. Liminal Spaces is, in a way, a series of self-portraits.

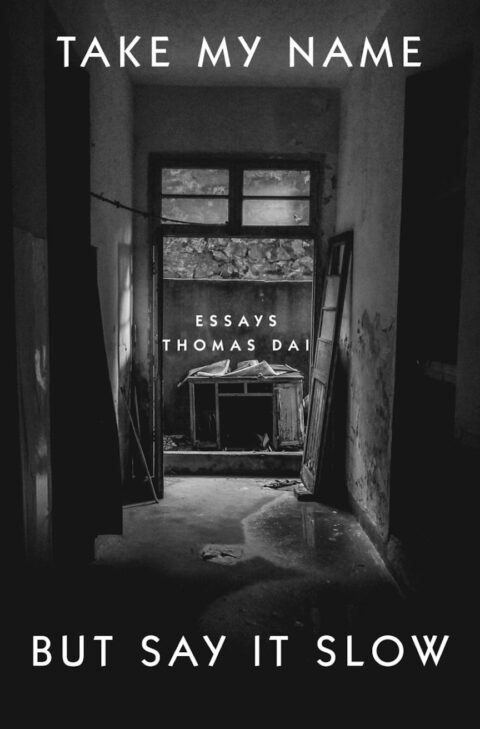

Liminality isn’t a popular sensibility in essay-writing these days — more often, authors assert their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and more in assured ways. I am this, which means that, is the general idea. Thomas Dai, to his credit, is stuck on the “I am this” part. In his debut essay collection, Take My Name but Say It Slow, he’s focused on the limits of identity. Like everyone, he has a host of identities he can choose from: in his case queer, Chinese-American, Southern. But none, he recognizes, really do the job of properly locating him. He’s rejected his given Chinese name, Nuocheng (itself a variant on his American hometown, Knoxville, Tennessee), and considers how much this has left him “smudged, an incomplete erasure of heritage and color.” This isn’t a book about hybridity, where different identities make a new whole; it’s about liminality, which shatters.

Liminality isn’t a popular sensibility in essay-writing these days — more often, authors assert their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and more in assured ways. I am this, which means that, is the general idea. Thomas Dai, to his credit, is stuck on the “I am this” part. In his debut essay collection, Take My Name but Say It Slow, he’s focused on the limits of identity. Like everyone, he has a host of identities he can choose from: in his case queer, Chinese-American, Southern. But none, he recognizes, really do the job of properly locating him. He’s rejected his given Chinese name, Nuocheng (itself a variant on his American hometown, Knoxville, Tennessee), and considers how much this has left him “smudged, an incomplete erasure of heritage and color.” This isn’t a book about hybridity, where different identities make a new whole; it’s about liminality, which shatters.

So how do you identify yourself when traditional modes of identification, right down to your very name, are troubled? Take My Name is essentially a catalogue of the methods, all imperfect, that he’s chosen. He could use maps, but maps are deceptive and unreal. He can travel — and he does, broadly, from the South to the Southwest and across China — but travel contains its own deceptions about the unity of residents and the kind of improvement or clarity allegedly on offer. “Travel took ordinary life and laminated it, imparting this formal feeling, this fantasy of a plot,” he writes. “I went somewhere. I came back.”

He can jog through the landscape, as he does as an MFA student in Tucson, Arizona. He can drive through it, as he does mimicking Vladimir Nabokov’s own travels chasing butterflies. He can borrow the archeologist’s tool of the transect, scrutinizing a small portion of his landscape in granular detail. He can read — histories, poems, lovers’ scratchings on tree trunks and rocks. He can look: The book contains his photos of interiors of Shanghai buildings designated for demolition — overgrown, eerie, dilapidated, all perfect candidates for Liminal Spaces.

Yet no one approach will satisfy. Dai’s point, of course, is that the searching is the identity, that we become most fully ourselves when we’re most alert to our uncertainty. To that end, Dai’s observations usually feature a doubling back against any kind of concrete statement about a place or a people. “There are Asian people in the South — millions of them, in fact — but that doesn’t mean they feel Southern,” he notes. Elsewhere, he writes of his Asian travels, “I was trying to align myself with the world rather than one of its many nations.” This qualifies as a kind of cosmopolitanism, but since that serves as an identity as well, he’s suspicious of it.

Still, for all the atomization that Dai uncovers, he recognizes that the essayist’s job is to bring some kind of order to the internal chaos. And Dai is an excellent curator of metaphors that capture the way that “I” is a fluid, ever-changing thing. Naturally, rivers play a role. Discussing Norman MacLean’s novella A River Runs Through It and William Carlos Williams’ book-length poem Paterson, Dai writes, “I want to learn how to form ties to new waterways while also honoring riparian pasts; how to connect to land and waterscapes in a longitudinal, accumulative way — the way of constant return, but not always to one’s origins.” In this essay, rivers give Dai both a metaphor and a structure — he shifts from literature to personal history to travelogue to capture the way we can feel of a piece and yet also ever-changing. “It is from so many scattered points that a river gathers its materials,” he writes.

Still, for all the atomization that Dai uncovers, he recognizes that the essayist’s job is to bring some kind of order to the internal chaos. And Dai is an excellent curator of metaphors that capture the way that “I” is a fluid, ever-changing thing. Naturally, rivers play a role. Discussing Norman MacLean’s novella A River Runs Through It and William Carlos Williams’ book-length poem Paterson, Dai writes, “I want to learn how to form ties to new waterways while also honoring riparian pasts; how to connect to land and waterscapes in a longitudinal, accumulative way — the way of constant return, but not always to one’s origins.” In this essay, rivers give Dai both a metaphor and a structure — he shifts from literature to personal history to travelogue to capture the way we can feel of a piece and yet also ever-changing. “It is from so many scattered points that a river gathers its materials,” he writes.

Dai writes elegantly, but this isn’t idle, belletristic woolgathering — there are stakes to this, because others’ attempts to simplify his identity are restrictive, even violent. “My uncertainty stems in part from how difficult it has been for Asian men in America, whether straight, gay, or neither, to see themselves as romantic protagonists,” he writes; elsewhere, he recalls being drunkenly bullied outside a Tucson dance club as “Chinese takeout.” “The man slurs at me, repeatedly, ‘What are you? What are you? What are you?’”

That dismal, infuriating scene of bigotry is common in identity essays, but as much as Dai wants you to see it, he also doesn’t want to dwell on it: Shortly after he’s dismissed as a “queer fuck,” Dai and his friend, an Asian woman who’s “closeness is [in] our difference,” have run off. “What are you? the man asks, but what I am is gone,” he writes. No confrontation would resolve his identity, and would only deal with one element of it anyway.

The strongest essay here, the clearest discussion of the meaning of liminality for him, comes not from his real travels but his virtual ones. In “Queer Cartographies,” he writes about the website queeringthemap.com, where LGBTQ+ users can anonymously place a pin in crucial locations regarding their sexuality — first kiss, first coming-out, and so on. The site is like that river that gathers its materials from everywhere, identity-affirming, a clear answer to “What are you?” But for Dai, it’s also bittersweet. “So many of the queer moments that appear on this map are momentary, ephemeral — not exactly the building blocks of a distinctive gay cosmos,” he writes. The problem with the fluidity of existence is that what once existed can get washed away. But Dai sees the value of the kind of monuments — a push-pin on a map, a name, an essay — that offer a sense of who we were, or are, or will become.

[Published by W.W. Norton on January 21, 2025, 288 pages, $28.99 hardback.]