In 1831, some five years before he began his career as a showman, P. T. Barnum grew concerned about the rise of religious zeal and sectarianism in Connecticut. As a local politician, he had argued against blue laws prohibiting gambling. To rub it in the faces of Calvinist church elders, he launched a weekly newspaper called The Herald of Freedom. The powers retaliated. He wrote in his autobiography, “I was indicted for informing the readers of my paper that a certain lay dignitary of a church in Bethel had ‘been guilty of taking usury of an orphan boy.’ Criminal prosecution was instituted against me.”

Fined and sentenced to 60 days in jail, Barnum was just getting warmed up. From his cell he organized a celebration for the day of his release. A procession of carriages, led by a band, carried him off to a highly publicized dinner during which the Rev. Theophilus Fisk orated on the “foul barbarity” of jailing Barnum “for having dared to untrammel his press.” Barnum scored a media relations victory that elevated his status as the hero of the common man.

Fined and sentenced to 60 days in jail, Barnum was just getting warmed up. From his cell he organized a celebration for the day of his release. A procession of carriages, led by a band, carried him off to a highly publicized dinner during which the Rev. Theophilus Fisk orated on the “foul barbarity” of jailing Barnum “for having dared to untrammel his press.” Barnum scored a media relations victory that elevated his status as the hero of the common man.

Unlike their European forerunners, the producers of the American circus were compelled to usurp mainstream morality from the church. This was a necessary market-making tactic, essentially American. Excitement would be “edifying.” At the same time, spectacle would become a long-term business strategy and not merely a one-time bizarre attraction. Barnum’s first show centered around the exhibit of a blind and partially paralyzed African-American slave named Joice Heth (1756-1836) who sang hymns. When she died, Barnum staged her autopsy for an audience of 1500 at fifty cents a seat. By the time of his great big-top shows, the word “circus” didn’t even appear in the title: “P.T. Barnum’s Great Traveling World’s fair, Museum, Menagerie, Polytechnic Institute and International Zoological Garden.”

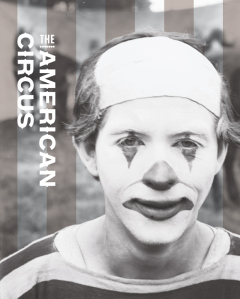

I recently discovered two important books on the American circus. The first is The American Circus, a collection of seventeen essays, contributed by American Studies scholars and curators, that look broadly across the significant attributes of the circus – with titles like “American Circus Posters,” “Elephants and the American Circus,” “Circus Music in America,” “The Americanization of the Circus Clown,” “The Circus Parade,” and “Disability and the Circus.” In “The Circus Americanized,” Janet M. Davis establishes the book’s main themes: “Transformed by the nation’s peculiar historical contingencies of geography, demography, expansionism, and technological modernization, the circus became an iconic American popular entertainment during the nineteenth century. Its itinerancy, bigness, and endless capacity for novelty and reinvention made it American.”

Edited by Susan Weber, Kenneth Ames and Matthew Wittman, all of the Bard Graduate Center, The American Circus is a large-format book, beautifully designed and amply illustrated. It’s a rich diversion – and it constantly reminds us that the American circus was a nexus for major currents and controversies in the culture – the economics of nationwide business, the portrayal of popular virtue, the role of animals in entertainment, the coming of the steam engine and other technologies, and the use of art for advertising.

Edited by Susan Weber, Kenneth Ames and Matthew Wittman, all of the Bard Graduate Center, The American Circus is a large-format book, beautifully designed and amply illustrated. It’s a rich diversion – and it constantly reminds us that the American circus was a nexus for major currents and controversies in the culture – the economics of nationwide business, the portrayal of popular virtue, the role of animals in entertainment, the coming of the steam engine and other technologies, and the use of art for advertising.

In “The WPA Circus in New York,” editor Susan Weber notes that during its four-year run starting in 1935, the circus still faced objections. After a performance in Central Park, “parents contacted the New York Parks Department complaining that they found the circus performance to contain ‘vulgar and suggestive sequences.’” (A clown had a string of firecrackers attached to his trousers. Another wore balloons on his chest – and was ordered to wear a coat over them.) But also, certain members of Congress objected to “the leftist politics that inflected many of its varied productions.”

The second book I found and deeply admire is Circus: The Photographs of Frederick W. Glasier, edited by Peter Kayafas and Deborah W. Walk with image interpretation by John T. Hill. Frederick Glasier (1866-1950) was a contemporary of Eugène Atget, Ernest Bellocq and August Sander, the masters of the large-format view camera (using glass plates) who produced their major work between 1890 and 1925. Glasier was a local commercial photographer, working in Brockton, Massachusetts where he had moved from the western part of the state in 1896. But then, in 1899, the circus came to Brockton. In his introduction, Luc Sante suggests that Glasier probably traveled with the Barnum and Bailey circus and perhaps later with the Sparks circus. He also continued to shoot circuses when they played each year in his town. After his death, Glasier’s wife sold the complete collection of 1,700 images to a collector who in turn sold them to the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida.

The second book I found and deeply admire is Circus: The Photographs of Frederick W. Glasier, edited by Peter Kayafas and Deborah W. Walk with image interpretation by John T. Hill. Frederick Glasier (1866-1950) was a contemporary of Eugène Atget, Ernest Bellocq and August Sander, the masters of the large-format view camera (using glass plates) who produced their major work between 1890 and 1925. Glasier was a local commercial photographer, working in Brockton, Massachusetts where he had moved from the western part of the state in 1896. But then, in 1899, the circus came to Brockton. In his introduction, Luc Sante suggests that Glasier probably traveled with the Barnum and Bailey circus and perhaps later with the Sparks circus. He also continued to shoot circuses when they played each year in his town. After his death, Glasier’s wife sold the complete collection of 1,700 images to a collector who in turn sold them to the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida.

Sante writes, “Glasier’s circus world is the magnificent realization of everything we have ever thought we knew about the circus, more classic and sexy and dignified and strange than anything we are likely to have seen in our own experience. Taken together, his pictures compile drama and intimacy, close-up and long-shot, center and periphery, teeming masses and solitude, posed and candid, into a 360-degree view so complete that it is more like a movie than a set of stills.”

Deborah Walk’s tersely illuminating comments on the photographs seem perfectly matched to their subjects. Of “Gertrude Dewar, Mademoiselle Omega, Brockton fair, Massachusetts, 1908” (shown, left), he says, “For the Brockton Fair outdoor shows, performers were drawn from vaudeville, the circus and other entertainment venues. Mademoiselle Omega on the “Silver Wire” was one of twenty-two big acts that were presented to more than 90,000 people during the four-day event.” He writes of “Joan of Arc, Circa 1912,” “The story of the Maid of Orleans, who confronted authority6 with inspired leadership, resonated in a world pulled by the realities of war and cultural changes created by the women’s suffrage movement.”

Deborah Walk’s tersely illuminating comments on the photographs seem perfectly matched to their subjects. Of “Gertrude Dewar, Mademoiselle Omega, Brockton fair, Massachusetts, 1908” (shown, left), he says, “For the Brockton Fair outdoor shows, performers were drawn from vaudeville, the circus and other entertainment venues. Mademoiselle Omega on the “Silver Wire” was one of twenty-two big acts that were presented to more than 90,000 people during the four-day event.” He writes of “Joan of Arc, Circa 1912,” “The story of the Maid of Orleans, who confronted authority6 with inspired leadership, resonated in a world pulled by the realities of war and cultural changes created by the women’s suffrage movement.”

As Sante notes, Glasier’s establishing shots “are seldom short of monumental,” while his portraits manage to gaze directly at the actual personalities of the performers. Glasier may be virtually unknown except to aficionados of circus history, but his photographs deserve a place among the major achievements of his era. Many of the most utterly moving and exciting shots in Circus are not freely available on the Internet – such as “Manicuring the Bulls, Circa 1910” (a recumbent elephant in a tent, two men atop it, seven elephants in the background) or “Miss May Lillie, 1908,” (a sharpshooter, aiming her revolver at the camera). But fortunately, I can share “Queen, The High Diving Horse, Brockton Fair, Circa 1899” (shown left).

As Sante notes, Glasier’s establishing shots “are seldom short of monumental,” while his portraits manage to gaze directly at the actual personalities of the performers. Glasier may be virtually unknown except to aficionados of circus history, but his photographs deserve a place among the major achievements of his era. Many of the most utterly moving and exciting shots in Circus are not freely available on the Internet – such as “Manicuring the Bulls, Circa 1910” (a recumbent elephant in a tent, two men atop it, seven elephants in the background) or “Miss May Lillie, 1908,” (a sharpshooter, aiming her revolver at the camera). But fortunately, I can share “Queen, The High Diving Horse, Brockton Fair, Circa 1899” (shown left).

Exquisitely produced, Circus includes 73 tritones on a page format of 12.5 x 12 inches. The book was printed and bound in Italy by Trifolio S./R.I., Verona.

[The American Circus, 472 pages, 327 color illustrations, $65.00. Published by Yale University Press on October 23, 2012.

Circus: The Photographs of Frederick W. Glasier, 168 pages, $75.00. Published by Eakins Press Foundation on August 15, 2009]