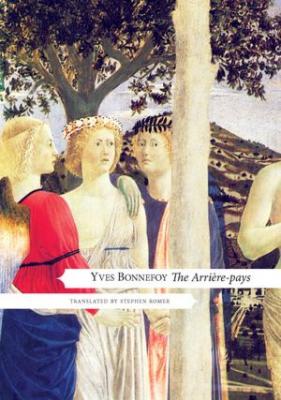

“I have often experienced a feeling of anxiety at crossroads,” begins Yves Bonnefoy’s enraptured meditation on art, The Arrière-pays. “At such moments it seems to me that here, or close by, a couple of steps away on the path I didn’t take and which is already receding – that just over there a more elevated kind of country would open up, where I might have gone to live and which I’ve already lost.” None of the English versions of the phrase Arrière-pays satisfied Bonnefoy or his attuned translator, Stephen Romer – not “back country” or hinterland” or “landlocked” or “middle of nowhere.” Bonnefoy had in mind something closer to “a dream of civilizations superior to our own.”

But it isn’t a placid dream. Bonnefoy will soon turn 90 years old, and as Anglophone literary critics begin their lagging assessments, the disquietude triggered in him by le arrière-pays may provide some insights to his poetics. Bonnefoy may envision an “over there” while standing at the crossroads, but the fork in the road is a pivot-point between two potentialities and barely a “here” at all. The road not taken demands another one chosen (though how does one choose and arrive at a superior civilization?). For Bonnefoy, poetry exists in the balance and the gap.

But it isn’t a placid dream. Bonnefoy will soon turn 90 years old, and as Anglophone literary critics begin their lagging assessments, the disquietude triggered in him by le arrière-pays may provide some insights to his poetics. Bonnefoy may envision an “over there” while standing at the crossroads, but the fork in the road is a pivot-point between two potentialities and barely a “here” at all. The road not taken demands another one chosen (though how does one choose and arrive at a superior civilization?). For Bonnefoy, poetry exists in the balance and the gap.

But even that partitioning of zones may be too exclusive. I prefer to say, at the risk of smudging what is typically particular and provocative in Bonnefoy’s many essays on art and writing, that he has liked to keep himself guessing, even confused. Certainly, this pilgrimage for insights that are superior to his own is the thread of The Arrière-pays, a tour through memories of visiting and viewing great works of art in Italy and other countries, a search for that “other place” in artistic imagery.

Speaking of Piero della Francesca, Bonnefoy writes, “However empirical he is at the confines of his art, and however conscious of what calculation cannot attain, the fact remains that he thought about his representation, and the instant of thought leaves a trace, like an excess of clarity, and is at the expense of true presence which is grounded in the invisible.” Most of Bonnefoy’s abiding philosophical and poetic ideas are contained in that statement. The “true presence” is elsewhere – and yet, he has argued against too much leaning on the Gnostic. As John Taylor writes in Into the Heart of European Poetry, Bonnefoy has disparaged “how human beings fail to turn away from an alluring ‘background’ of myths, tales, ‘gnostic dreams,’ fantasies, intellectual ‘concepts’ or religious credences, and toward ‘what exists here, now, in our essential finitude.’” Then why does he worry about violating “the true presence which is grounded in the invisible”?

Speaking of Piero della Francesca, Bonnefoy writes, “However empirical he is at the confines of his art, and however conscious of what calculation cannot attain, the fact remains that he thought about his representation, and the instant of thought leaves a trace, like an excess of clarity, and is at the expense of true presence which is grounded in the invisible.” Most of Bonnefoy’s abiding philosophical and poetic ideas are contained in that statement. The “true presence” is elsewhere – and yet, he has argued against too much leaning on the Gnostic. As John Taylor writes in Into the Heart of European Poetry, Bonnefoy has disparaged “how human beings fail to turn away from an alluring ‘background’ of myths, tales, ‘gnostic dreams,’ fantasies, intellectual ‘concepts’ or religious credences, and toward ‘what exists here, now, in our essential finitude.’” Then why does he worry about violating “the true presence which is grounded in the invisible”?

The distinctions he makes are exceedingly fine ones. In his essay “The Act and the Place of Poetry,” he prescribes what should be occurring here (in our work) as we contemplate there: “We must ask ourselves … whether poetic invention brings nothing to the life of the writer other than aimless desire, unrest, and futility … I should like to show that this is not the case. To think so would be to misunderstand this world of expectancy in which, having reached this point in the invention of speech, we are involved. Here, where nothing is considered, sought, or loved but the act of presence, where the only valid future is that absolute present where time evaporates, all reality is still to be, and its ‘past’ as well.”

Bonnefoy has published six volumes of poetry over the past twenty years (and fourteen others previously, starting with Traité du pianiste in 1946). Some of Hoyt Rogers’ translations of Bonnefoy’s late work first appeared in the October 2000 “French” issue of Poetry (co-edited by John Taylor). In Second Simplicity, Rogers has selected and translated work from those collections, revealing Bonnefoy’s remarkable inventiveness and desire to accommodate whatever form of address is called for, whether in verse or prose.

* * * * * * * *

A PHOTOGRAPH

This photograph is truly pathetic:

Coarse colors disfigure the mouth,

The eyes. Mocking life with color –

Back then it was par for the course.

But I knew the man whose face was caught

In this net. I seem to see him going down

Into the boat. Already with the coin

In his hand, just as when someone dies.

I want a wind to rise in this image, a rain

That will soak it, wash it away – so the steps

Beneath those colors will glisten and shine out.

Who was he? What were his hopes? All I hear

Is his footfall in the night. Awkward, he risks

His way down, and without a helping hand.

In his 1994 Paris Review interview, Bonnefoy reiterated his reservations about art and poetry – which has been his way of celebrating them. He said, “For poetry can only be a partial approach, which substitutes for the object a simple image and for (our feelings) a verbal expression — thereby losing the intimate experience. On the other hand there is nothing before language, for there is no consciousness, and therefore no world, without a system of signs. In fact, it is the speaking-being that has created this universe, even if language excludes him from it. This means that we are deprived through words of an authentic intimacy with what we are, or with what the Other is. We need poetry, not to regain this intimacy, which is impossible, but to remember that we miss it and to prove to ourselves the value of those moments when we are able to encounter other people, or trees, or anything, beyond words, in silence.”

In his 1994 Paris Review interview, Bonnefoy reiterated his reservations about art and poetry – which has been his way of celebrating them. He said, “For poetry can only be a partial approach, which substitutes for the object a simple image and for (our feelings) a verbal expression — thereby losing the intimate experience. On the other hand there is nothing before language, for there is no consciousness, and therefore no world, without a system of signs. In fact, it is the speaking-being that has created this universe, even if language excludes him from it. This means that we are deprived through words of an authentic intimacy with what we are, or with what the Other is. We need poetry, not to regain this intimacy, which is impossible, but to remember that we miss it and to prove to ourselves the value of those moments when we are able to encounter other people, or trees, or anything, beyond words, in silence.”

In “The Anchor’s Long Chain,” a prose sequence included in Second Simplicity, Bonnefoy resumes his obsession with le arrière-pays — and suggests a narrowing of the space between the written work and the mysterious Other:

“Words offer their full meaning only when we observe what they say ‘over there,’ on a horizon. Here, we see too much detail our mind bogs down in too many byways, marshals too many phrases – so everything is bent to our will to possess, to comprehend. Over there, the whole prevails over its parts, and things become beings again.”

In other places, Bonnefoy suggests that art is the Other Place. So it seems that Bonnefoy clouds the medium through which he escapes to write his poetry. His classic essays on Shakespeare, Baudelaire, Mallarmé and many others allowed him to rev his engines, clarify his values, honor and critique his influences, and perhaps empty himself of ideas so that, in the poetry, he would elude entanglement in “too many byways.” He has warned against too much conceptualism. In “In a Shard of Mirror” in Second Simplicity, he says, “Poetry owes a debt to what’s truly important: compassion, and the humility that it instills. Those who want to raise poetry to some loftier plane of the mind are arrogant: they refuse to accept the narrow limits of the human condition. Their excesses make poetry fall prey to evil, which may win out because of their meddling. They’d be better off just being stupid …”

In other places, Bonnefoy suggests that art is the Other Place. So it seems that Bonnefoy clouds the medium through which he escapes to write his poetry. His classic essays on Shakespeare, Baudelaire, Mallarmé and many others allowed him to rev his engines, clarify his values, honor and critique his influences, and perhaps empty himself of ideas so that, in the poetry, he would elude entanglement in “too many byways.” He has warned against too much conceptualism. In “In a Shard of Mirror” in Second Simplicity, he says, “Poetry owes a debt to what’s truly important: compassion, and the humility that it instills. Those who want to raise poetry to some loftier plane of the mind are arrogant: they refuse to accept the narrow limits of the human condition. Their excesses make poetry fall prey to evil, which may win out because of their meddling. They’d be better off just being stupid …”

Bonnefoy takes a long view of history. He came to Paris as a young man during the Occupation to breathe in the last draughts of surrealism and then developed his own manner. He has watched as French thinkers sold the West, especially the American academy, on the mutual internalizations of art and theory. He seems to object or at least doubt, even while having inherited Roland Barthes’ chair of comparative study at the Collège de France. His teaching consists of assertions like: “The longing for the true place is the vow made by poetry … There is no method for returning to the true place. It may be infinitely close. It is also infinitely far away. So it is with being, in our moment of time, and the irony of presence” (from “The Act and the Place of Poetry”). He acknowledges the post-modern sense that words have a “well-known incapacity to express the immediate” – but he feels that building art on word-theory only clarifies or emphasizes that incapacity while he has “only asked of words that they put their trust in silence.”

“PASSER-BY, THESE ARE WORDS …”

Passer-by, these are words. But instead of reading

I want you to listen: to this frail

Voice like that of letters eaten by grass.

Lend an ear, hear first of all the happy bee

Foraging in our almost rubbed-out names.

It flits between two sprays of leaves,

Carrying the sound of branches that are real

To those that filigree the unseen gold.

Then know an even fainter sound, and let it be

The endless murmuring of all our shades.

Their whisper rises from beneath the stones

To fuse into a single heat with that blind

Light you are as yet, who can still gaze.

Listen simply, if you will. Silence

is a threshold

Where, unfelt, a twig is breaking in your hand,

As you attempt to disengage

A name upon a stone:

And so our absent names untangle your alarms.

And for you who now move on, pensively,

Here becomes there without ceasing to be.

Hoyt Rogers has continued to work on and improve his earlier versions, such as the one above which appeared first in Partisan Review in 2001. But most of Second Simplicity has never been pub lished in English. Also, The Arrière-pays, published in 1972, appears now in English for the first time. Stephen Romer’s translation manages to capture both Bonnefoy’s precision of statement and perception and his discomfiture and restlessness. The narrative tracks a traveler who in turn is hunting for the presence of le arrière-pays while planning a text called An Unknown Feeling. Bounding between exaltation and constraint, he ultimately seems to settle for a recognition of presence in the world itself, not in the dream. He writes:

Hoyt Rogers has continued to work on and improve his earlier versions, such as the one above which appeared first in Partisan Review in 2001. But most of Second Simplicity has never been pub lished in English. Also, The Arrière-pays, published in 1972, appears now in English for the first time. Stephen Romer’s translation manages to capture both Bonnefoy’s precision of statement and perception and his discomfiture and restlessness. The narrative tracks a traveler who in turn is hunting for the presence of le arrière-pays while planning a text called An Unknown Feeling. Bounding between exaltation and constraint, he ultimately seems to settle for a recognition of presence in the world itself, not in the dream. He writes:

“It is in my own becoming, that I can keep open – and not in a closed text – this vision, this intimate knowledge; it is there, it can take root and flourish and bear fruit if, as I think, it has meaning for me. That would be the crucible in which the arrière-pays, having dissolved, would re-form, and where a few words would shine, possibly, and while being simple and transparent – like that emptiness, language – would yet be everything, and real.”

Looking at Caravaggio’s Raising of Lazarus and Piero’s Resurrection, he says, “Great art? It consists in not forgetting the here and now in the dream of elsewhere, in not forgetting time, humble time as it is lived through here, among the illusions of the other place, that shade existing out of time.”

He has sustained a long, contentious and obligatory journey to make his poems possible.

* * * * * * * * *

The Arriere-pays, with a new preface by Yves Bonnefoy and introduction by Stephen Romer, published by Seagull Books on August 15, 2012, 165 pages, $25.00 hardcover. Includes 20 color plates.

Second Simplicity: New Poetry and Prose, 1991-2011, translated by Hoyt Rogers, published by Yale University Press on January 24, 2012, 320 pages, $30.00 hardcover

Bonnefoy’s essay, “The Act and the Place of Poetry,” may be found in the collection of selected essays by that title, edited and introduced by John T. Naughton, University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Bonnefoy’s 1994 Paris Review interview may be accessed by clicking here.

Bonnefoy

This reviews does what all excellent reviews succeed in doing – sending us to read what’s under review. Thank you.

Bonnefoy review

Wondering who wrote this review. I suspect the name is there, but I haven’t found it. Thanks.

C’est moi, Ron Slate

C’est moi, Ron Slate

Bonnefoy & his reviewer

There’s not a little of Bonnefoy in the shape and echoes of the review itself. Maybe that’s a testament to the power of his work. My only pushback has to do with what you say about his aversion to theory etc etc. Has he really been explicit about that? I can accept your extrapolations given his constant repetition of his mantra. He coined a word for the problem, “excarnation.” Nice poems in the review, too, even if he keeps to the idea of a concrete speaker. What I mean is, he won’t give up on the idea of a spiritual person in charge of the speaking. No, he’s no post-avantgardian. Hope they put this book out in paperback.

Bonnefoy

Lone Shark, you seem to suggest there’s something wrong with the narrative voice in the poems, similar to the way third-person omniscience has often been criticised (wrongly, in my opinion). Or have I misunderstood you?

Bonnefoy’s voice

Forgive my fuzziness. I mean only that he has remained a pretty conventional poet since he has preserved the first-person concept, and it is only a concept even though he has warmed against too much conceptualism as RS said. In that sense Mallarme was more experimental than Bonnefoy. But Bonnefoy gives us something else which in the review above is referenced by the word “humble,” Bonnefoy’s notion of human limitations versus expansiveness. He does not warm up to the enthusiasms of postmodernism. Do you know that he has spent quite a bit of time in the US teaching etc and loves New England. He loves Emily Dickinson, another first-person specialist who creates a haunting and vital world of her own.

Re Yves Bonnefoy

I persuaded you to live on credit

Reading on the outskirts of town

Near the oil refinery I worked in

My girlfriend toiling in a cafeteria

It all looked like a Martian movie

Everything either a creep or a ghoul

That was then and this is now, it’s said

But Yves Bonnefoy, I loved your name.