Near the end of his life, Robinson Jeffers wrote a short lyric called “On an Anthology of Chinese Poems” in which he extols the virtues of the poets and their verse:

Beautiful the hanging cliff and the wind-thrown cedars, but they have no weight.

Beautiful the fantastically

Small farmhouse and ribbon of rice-fields a mile below; and billows of mist

Blow through the gorge. These men were better

Artists than any of ours, and far better observers. They loved landscape

And put man in his place. But why

Do their rocks have no weight? They loved rice-wine and peace and friendship,

Above all they loved landscape and solitude.

— Like Wordsworth. But Wordsworth’s mountains have weight and mass, dull though the song be.

Is it a moral difference perhaps?

In Soul Says, Helen Vendler calls this poem “his most honest piece of self-examination … His plaintive question, ‘But why / Do the rocks have no weight?’ is the cry of the Christian against the Confucian.” She suggests that Jeffers suddenly, late in life, had begun to wonder if his Californian coastal landscape was less “inhuman” than he had long portrayed it.

In Soul Says, Helen Vendler calls this poem “his most honest piece of self-examination … His plaintive question, ‘But why / Do the rocks have no weight?’ is the cry of the Christian against the Confucian.” She suggests that Jeffers suddenly, late in life, had begun to wonder if his Californian coastal landscape was less “inhuman” than he had long portrayed it.

But in this poem, Jeffers is not embracing an alternate, placid depiction of nature. On the contrary, he is admitting an inability to enter into the language and mentality of the Chinese poem, even in translation. The concluding question is hardly rhetorical; moral considerations yield no clarity here. The Christian, schooled in Greek and tutored by Plato, has hit a wall. The simple beauty of the poems is acknowledged — but the poems point beyond beauty, a static state on the page, to an unnamed process and coherence.

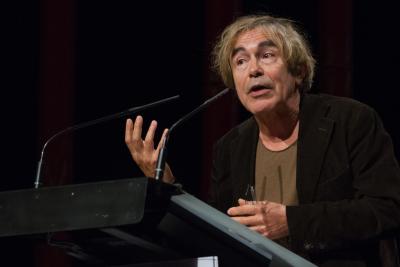

For François Jullien, conceding the failure to enter another culture and its language is the essential first step toward gaining access. Since publishing his first works in the late 1970’s, he has become France’s preeminent sinologist-philosopher. Wagging a finger at fellow sinologists, he censures them for shrinking from the most basic question: “What is it to enter a way of thought?” Then, he warns that the way in won’t be easy: “No synopsis — no abridged, condensed digest — can give us access to it … what remains a given is the idea that the cultures and thinking of elsewhere, as complex and varied as they may be, cannot or can only marginally call into question European questioning.”

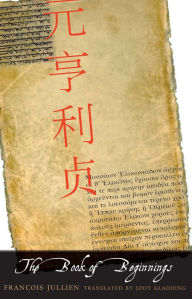

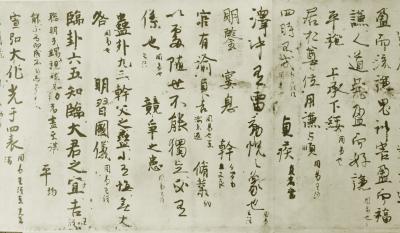

In The Book of Beginnings, Jullien rewinds our presumed understanding of Chinese thought and considers “one simple Chinese sentence, but so ‘simple’ that it takes much time to reveal it” — from China’s oldest book, the Yijing (I Ching). The sentence reads: “beginning/yuan expansion/heng profit/li rectitude/zhen.” This raises yet another question: what is a sentence? Can the Westerner equip oneself to enter truly into a language without syntax?

In The Book of Beginnings, Jullien rewinds our presumed understanding of Chinese thought and considers “one simple Chinese sentence, but so ‘simple’ that it takes much time to reveal it” — from China’s oldest book, the Yijing (I Ching). The sentence reads: “beginning/yuan expansion/heng profit/li rectitude/zhen.” This raises yet another question: what is a sentence? Can the Westerner equip oneself to enter truly into a language without syntax?

The Book of Beginnings reads like an exhortative plan for a prison break spoken to complacent inmates. Jullien not only picks apart the Chinese “sentence” but also dissects the beginning of Genesis and the triggering concepts of Platonic thought. The shape and sound of his argument — recurrent, back-tracking, leaping ahead, inventively phrased, always urgent — become the book’s great pleasures and suggest Jullien’s own struggle. Although he criticizes our ingrown habits, he digs out from beneath them like the rest of us. It soon becomes clear that the book has more than sinology on its mind — such as concepts of time, literature, history, theology and cosmology, the mechanics and illusions of translation, and the universality of philosophy. As Jullien magnifies the Chinese processive orientation and its absence of a fallen, founding world that must either be restored, improved or fall further into ruin, history itself becomes a wobbly concept. He writes about the first Chinese sentence:

“Because it does not problematize, does not raise itself to the level of reasoning, this Chinese thinking about the beginning escapes the question of its truth … Isolating itself in establishing its internal relationship, it dispenses with external justification … It may be surprising that so short and major a text would have drawn so little attention from translators … The utterance is too elementary, not outstanding or troubling enough, not partial enough; in short, it offers too little hold or angle to stimulate desire or capture interest. Would hat be the only reason, however? Isn’t it also that, since it lends itself so conveniently to stereotypical usage, since it invents or forges nothing, is at stage zero of theoretical function and fiction, it is most difficult for a European reader to apprehend: because it does not allow for divergence or give way to speculation.”

“Because it does not problematize, does not raise itself to the level of reasoning, this Chinese thinking about the beginning escapes the question of its truth … Isolating itself in establishing its internal relationship, it dispenses with external justification … It may be surprising that so short and major a text would have drawn so little attention from translators … The utterance is too elementary, not outstanding or troubling enough, not partial enough; in short, it offers too little hold or angle to stimulate desire or capture interest. Would hat be the only reason, however? Isn’t it also that, since it lends itself so conveniently to stereotypical usage, since it invents or forges nothing, is at stage zero of theoretical function and fiction, it is most difficult for a European reader to apprehend: because it does not allow for divergence or give way to speculation.”

Jullien’s colleagues, jetting around from university to institute, ask: “Isn’t it obvious that cultures no longer exist apart from one another?” Where they see thresholds, he sees chasms. “In order to translate, it is necessary to help another possibility get through,” he writes. “and not to hurry this transition; not to step over the difficulty, not to mask it, but to unfold it … it is a matter of maintaining oneself at the breach as long as possible.”

What one culture renounces in its founding ideas, the other embraces. Does translation represent a third way? A recombination of two traditions? Jullien quite intentionally leaves us on the brink of such questions. He prefers “fund of understanding” to “tradition” since the latter may be reactionary while the former is “neither restrictive nor closed … ‘tradition’ is very often only a curtain drawn over the lack of analysis.” So there.

What one culture renounces in its founding ideas, the other embraces. Does translation represent a third way? A recombination of two traditions? Jullien quite intentionally leaves us on the brink of such questions. He prefers “fund of understanding” to “tradition” since the latter may be reactionary while the former is “neither restrictive nor closed … ‘tradition’ is very often only a curtain drawn over the lack of analysis.” So there.

The Book of Beginnings is ultimately an encouraging, lively, and aspirational narrative offering an illumination in virtually every sentence. Jullien admits in his final note that the book is a manifesto — after more than three decades in the sinology business, he is dissatisfied, agitated, and even fearful: “The danger is that we may act globally in this fashion: that we do not translate between languages by illuminating the implied biases, which are also so many riches, but instead we superimpose and consequently bury.”

[Published by Yale University Press on May 26, 2015. 152 pages, $26.00 hardcover. Originally published by Editions Gallimard in 2012.]

translations

I don’t know. Maybe another example of that great French principle: “It works in practice but will it work in theory?” Isn’t he saying the more than obvious? There has been so much written about the act of translating — does anyone still think it’s a matter of finding direct correspondences?

Out of Translation

My students often tell me that the English translations of Chinese poems, whether traditional or contemporary, are either much better or much worse than the originals. I usually cough and say something along the lines of “Translation, it’s bloody difficult — you try doing it”, or “Translation, it’s an updraft of the first poem’s spirit– get over it.” Sometimes I even take credit for the beauty of my language. (They are rightly sceptical.) Yet I sometimes tell myself that their response doesn’t matter. Perfectionism is impossible. Our need for cross-cultural understanding is much bigger than us. At the end of the day however some cards fall very wrong, and it’s right that misunderstandings should not help. On the rare occasions when I have wanted to translate a Chinese poem into English, I confess that I brought all of my Western poetic notions and sensibilities to bear on that small poem. I’m always surprised when, after so much effort, we can all be astonished by the result. Translation in any sincere form is a most important and genuine project.