In anthologies of 20th century Italian poetry in English translation, one may find Saba, Campana, Ungaretti, Montale, Pavese, Pasolini and Scotellaro — but never Amelia Rosselli. Yet writing about her work in 1963 just before the publication of her first book, Variazioni belliche, Pasolini said, “I have never run across anything of its kind, so powerfully amorphous, so objectively superb.”  Lucia Re, who co-translated and published this first book with Paul Vangelisti as War Variations (Green Integer, 2003), regards Rosselli’s accomplishments as belonging among “Celan, Bachmann, Char, Pasternak, Akhmatova, and Plath, all of whom she loved.”

Lucia Re, who co-translated and published this first book with Paul Vangelisti as War Variations (Green Integer, 2003), regards Rosselli’s accomplishments as belonging among “Celan, Bachmann, Char, Pasternak, Akhmatova, and Plath, all of whom she loved.”

In her introduction to The Dragonfly, the first career-spanning selection of Rosselli’s work in English, Deborah Woodard notes that Rosselli was active among the experimental poets of “Gruppo 63” but “she remained on the sidelines, put off by the didactic nature of the discussion.” While the avant-garde poets regarded her as insufficiently politicamente impegnati, the mainstream literati found her work too oblique and formally erratic. She was never awarded a major Italian poetry prize. Woodard writes, “Although at no point was she without her circle of admirers, family and friends, the poet slipped into deepening isolation.” Her poetry spoke beyond category.

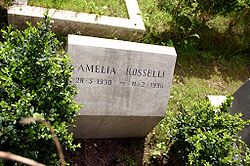

She had suffered from paranoia and depression since a childhood traumatized by war, Jew-hunting, and exile. Three years after Mussolini became the Italian prime minister in 1922, he was calling himself “Il Duce.” The Rosselli family sought refuge in Paris where Amelia was born. Her grandmother, Amelia Pincherle Rosselli, was a celebrated playwright and feminist. Her father and uncle, Carlo and Nello Rosselli, were prominent anti-Fascist resisters and writers. In 1937, Mussolini’s agents assassinated them at Bagnole-de-l’Orne in Normandy. Taken to England and America to escape the Nazi death camps, she returned to Rome after the war as a shaken adult. Rosselli’s second cousin, Alberto Moravia, helped her obtain translation work and guided her readings in Italian literature. But Rosselli also studied piano and composition in England, and made her modest living as a musicologist. On the anniversary of Plath’s death, Rosselli committed suicide by leaping from her fifth-story kitchen window into an interior courtyard.

She had suffered from paranoia and depression since a childhood traumatized by war, Jew-hunting, and exile. Three years after Mussolini became the Italian prime minister in 1922, he was calling himself “Il Duce.” The Rosselli family sought refuge in Paris where Amelia was born. Her grandmother, Amelia Pincherle Rosselli, was a celebrated playwright and feminist. Her father and uncle, Carlo and Nello Rosselli, were prominent anti-Fascist resisters and writers. In 1937, Mussolini’s agents assassinated them at Bagnole-de-l’Orne in Normandy. Taken to England and America to escape the Nazi death camps, she returned to Rome after the war as a shaken adult. Rosselli’s second cousin, Alberto Moravia, helped her obtain translation work and guided her readings in Italian literature. But Rosselli also studied piano and composition in England, and made her modest living as a musicologist. On the anniversary of Plath’s death, Rosselli committed suicide by leaping from her fifth-story kitchen window into an interior courtyard.

This is the first section of “5 Poems Towards a Poetics” from “Hospital Series,” written between 1963 and 1965:

Grant me chains of indulgence, rescue me from the ship that straight-

away goes down, lofty thought drives off the Argonauts from this

my dwelling of unknown dimensions; revive my supplicant lips

with alms, reduce to ash the remainder of my days

not so lockstep they can’t judge justice, transparent

if you verify it, though anything but a tranquil exploration.

Where is he who comes, he who goes, I’m none the wiser

and tramp up and down a countryman’s nightly meeting places: thick

hands rasped breath crystals of indifference, I don’t give a damn!

and I’m hurled against your target. Pressing on shifty merchants

skirting vicissitudes, no – I wanted to say, but it escaped me, the

urine and the moon and commerce innocently crystallized themselves

to kick me out – thus press on, sophisticated anguish of the

moons – thus make me understand! Night’s routine (a lively night

was the night) routine of not finding not understanding not forgiving

the bagatelle that’s my refrigerator, cudgels for the beast

so completely self-absorbed it begins sneezing.

Collision of beasts and of landslides, my dreams won’t leave

me in peace, thus press toward the pursuit of pleasure,

I seek only you.

Many of her poems of the 1950s are imagistic and terse, but soon the work bursts into lengthy, prosaic lines, her “chains of indulgence” voicing a “sophisticated anguish.” She writes in her long poem “The Dragonfly”:

I am one who

experiments with life and can’t allow any

rival to touch the heart, the insatiable limbs.

I am one who willingly leaves glory to the

rest but who regrets being held hostage by the

cursed lump in her throat. I am one among

many equally voracious but by God if I can

I’ll carve a different channel for my need and my

desires will be of a different stamp!

The mainstream couldn’t find any tight lyrics to anthologize among her books, and the work was both too personally disturbed and not frivolous enough for the avant-garde. But Pasolini, in his “Note on Amelia Rosselli,” took full notice. In her work he heard the violence of language alienated from itself: “It simply reveals in a horrible light of putrefied or ridiculous objectivity. Agony or death do not change the world.” One immediately thinks of Char in this way – but in Rosselli there is more gasping for air, flailing for chance impact.

The mainstream couldn’t find any tight lyrics to anthologize among her books, and the work was both too personally disturbed and not frivolous enough for the avant-garde. But Pasolini, in his “Note on Amelia Rosselli,” took full notice. In her work he heard the violence of language alienated from itself: “It simply reveals in a horrible light of putrefied or ridiculous objectivity. Agony or death do not change the world.” One immediately thinks of Char in this way – but in Rosselli there is more gasping for air, flailing for chance impact.

Woodard identifies the central conceit extending through her poems – a complex, antagonistic relationship with a double or a partner. “In Rosselli’s poetry, the double, or the sick lover, externalizes the author’s own malaise. Rosselli’s lover is not exactly dead, however, just comatose or exceptionally dense. To be heard by him, the poet must herself grow bellicose.” I would add that Rosselli’s persona is a daunting invention, an improbable transformation of what Pasolini called “a rationally inexpressible spiritual covering.” In “Bad Poetry For You,” a poem written for Massimo Ferretti, she begins, “With quick sure strokes: I bring you my celebration, my / celebrating of vain glory,” and she ends with, “And doesn’t promise to cripple you: or to clone you, it asks / only for a rematch, and to disown you.” Since the horror of the war was a permanent essence, her persona would be an acerbic goddess of battle, despondently ruthless in her homecoming.

By the mid-1970’s, Rosselli reverted to shorter lines and multi-sectioned long sequences, as in these pieces from “Poems”:

His serenity is

precisely what wasn’t

wanted the continuum of his

brotherly kiss.

***

the lira in your pocket

is cause for joy

hope of departure,

at the first sign of a spat

***

Though the sky which

with its gondolas would go by

through doors

far from the source

words ran away, astonished

without sounds of love.

A bully on the street trumps friendship.

Pasolini described Rosselli’s poetry as “a luxuriant, verdant oasis with the stupefying and random violence of brute fact at the edge of its domain.” In selections from “Obtuse Diary” (1954-1968) — startling prose with a piercing needle of narrative — Rosselli’s tone is stained with the world’s brutality – but as Pasolini observed, “Deformity implies a more integral capacity for resistance if it surrounds itself with an insurmountable wall of death and sacrality.” Rosselli writes, “Why not understand life for what it is; why not force life to understand itself? Why hadn’t she had a chance to understand life?”

Pasolini described Rosselli’s poetry as “a luxuriant, verdant oasis with the stupefying and random violence of brute fact at the edge of its domain.” In selections from “Obtuse Diary” (1954-1968) — startling prose with a piercing needle of narrative — Rosselli’s tone is stained with the world’s brutality – but as Pasolini observed, “Deformity implies a more integral capacity for resistance if it surrounds itself with an insurmountable wall of death and sacrality.” Rosselli writes, “Why not understand life for what it is; why not force life to understand itself? Why hadn’t she had a chance to understand life?”

These translations by Woodard and Leporace are selected to deliver the expansive bitterness, sorrow, and disappointment – but also, the irrepressible retaliatory power — of Rosselli’s core output. Also, the translators deal capably with her syntactical strangenesses, perhaps the result of her exposure to a swirl of languages during the most turbulent times in her youth. The Dragonfly is a daunting pleasure, an uninhibited exposure of desire and ruin. Rosselli knew her language would challenge the reader to be a worthy companion.

Ultimately, she came to believe that writing was futile, purposeless. This is a conclusion that arrives only after the poet has given everything to the art. Rosselli was utterly disinterested in the poet’s all too usual games — namely the reiteration of style and the display of affiliations. Again, from “Obtuse Diary”:

Ultimately, she came to believe that writing was futile, purposeless. This is a conclusion that arrives only after the poet has given everything to the art. Rosselli was utterly disinterested in the poet’s all too usual games — namely the reiteration of style and the display of affiliations. Again, from “Obtuse Diary”:

“There’s no world ready for me so I’m leaving for a world less ready for me, which will want me to suffer roundly for the sorrows that I don’t remember having suffered, and for my presumption: I still feel the old guilt of not having known how to be somebody …

And with a quickened spirit she cut both her hands.”

[Published by Chelsea Editions on June 1, 2009. 275 pages, $20.00 paperback. Available from www.ChelseaEditionsBooks.org]

Amelia Rosselli

I did not know her, but for the name, so thanks for this, Ron.

What a discovery

Thank you for bringing this poet to my attention. I’m amazed that we don’t know more about Rosselli and that her work hasn’t been celebrated. Certainly, as you say, Paul Celan has been recognized for having created unique poetry out of the Holocaust experience. But Rosselli seems to have created her own extreme sounds, very passionate and uncompromised. It’s a shame that it has taken so long for this poet to gain a little recognition among American readers. I have ordered copies of this book, thank you.

Amelia Rosselli

I did not know much about Rosselli before this post, great job.

Also nice use of sources-especially Pier Paolo.

Grazie mille.