The poems in Catherine Barnett’s two collections look unflinchingly at and come to terms with specific griefs and situations. Her signature gesture is the returning gaze. Her first book, Into Perfect Spheres Such Holes Are Pierced (Alice James Books, 2004), elegizes two nieces who died in 2000 when their Alaska Airlines flight crashed into the sea. They had been returning to Seattle from a weekend in Mexico with their father. The poems depict the faltering struggle of individuals and family to comprehend a staggering catastrophe and the state of “grief, the sheen we bring to wood / when with repetitive gestures we polish the raw thing.”

SITE, II

We were all she’s there –

sister, sister, sister, mother, friend, friend –

and by then we knew.

We sat on the floor in the mortuary looking as if for beauty

at a plate of jewelry and a room full of urns.

One urn pale wood,

one urn with two cloisonné cranes,

one urn blue steel with four bolts underneath.

My sister took a small brass cube from the velvet plate

and two hollow stars and a screw-top heart

she’s to fill with ash and hang from chains

around her neck. What was she thinking?

Who could pour ash into such tiny shapes?

And whose ash?

For one child we had a penny bag,

for the other not a thing.

The girls disappear into the ocean. The aunt-speaker asks, “so what are we to make of the whole disappearing?” (“Journal”). Barnett finds a voice chilled enough to contain a scalding helplessness. The speaking is also candid, brash in its serial returns to witness the aftershock. This is not the testimony of someone coming apart – it is a considered clawing back into the recently experienced moment with a story strapped on its back. The language is tensile, exact (in specifying its shakiness), uncomplicated. Grieving and its project: the elegy loves and is grateful to the object of remembrance for the opportunity to create elegy, to prove that something may be made out of disappearances.

The girls disappear into the ocean. The aunt-speaker asks, “so what are we to make of the whole disappearing?” (“Journal”). Barnett finds a voice chilled enough to contain a scalding helplessness. The speaking is also candid, brash in its serial returns to witness the aftershock. This is not the testimony of someone coming apart – it is a considered clawing back into the recently experienced moment with a story strapped on its back. The language is tensile, exact (in specifying its shakiness), uncomplicated. Grieving and its project: the elegy loves and is grateful to the object of remembrance for the opportunity to create elegy, to prove that something may be made out of disappearances.

A true exploit prefers to occur in ignorance of what’s at stake – what may be lost or gained. The conventional notion is that the poet is expert at gauging and consenting to the risk. But what she actually consents to is ignorance — which counts at least as much as other necessities such as technique or stamina. Ignorance may be the most often faked attribute in poetry. We know too much and mistrust our wisdom. In Into Perfect Spheres Such Holes Are Pierced, Barnett works so diligently at depicting the family’s situation that one may feel she is perhaps too aware of the stakes, too proud of that awareness and its precisions. The disorder is tamped down under great pressure. But I respond to the custodianship of the domestic, the animation of responsibility, the care in the coolness – and the rising heat of fear within it.

STILL LIFE WITH DEPARTURE

I watch my mother pack, tell her

leave something behind.

She’s wearing the black shoes I lent her,

and they fit her so much better than they ever fit me

she wants to keep them,

says she could walk forever in them.

For a long time she thought if she made one circle,

and circled that circle, she could keep us safe.

For a while it was true,

until the circle we were got filled with other circles,

water inside water, beginning inside end,

mouths inside each mouth and all calling.

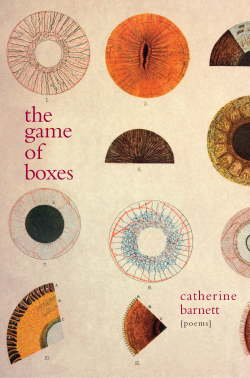

Graywolf Press has now published Barnett’s second collection, The Game of Boxes, and once again she treads a circle around a situation. But eight years after her first book, a strange and shrewd counterbalancing interactivity has developed between ignorance and stylishness. Where she used to insist on the availability of a string of minor-note reckonings, she now relents (“I’m studying the unspoken”). The Game of Boxes bears down on the subject of how to describe the world – parent to child, children among themselves, and between lovers. The provisional and partial nature of such description is not a consideration in her first book in which the confidence in an ability to preserve life through the dexterities of language is quite strong. The charms and provocations of The Game of Boxes spring out of the erosion of self-possession. Yet as uncertainty takes over rhetorically, there is an unabashed flair in the form.

Graywolf Press has now published Barnett’s second collection, The Game of Boxes, and once again she treads a circle around a situation. But eight years after her first book, a strange and shrewd counterbalancing interactivity has developed between ignorance and stylishness. Where she used to insist on the availability of a string of minor-note reckonings, she now relents (“I’m studying the unspoken”). The Game of Boxes bears down on the subject of how to describe the world – parent to child, children among themselves, and between lovers. The provisional and partial nature of such description is not a consideration in her first book in which the confidence in an ability to preserve life through the dexterities of language is quite strong. The charms and provocations of The Game of Boxes spring out of the erosion of self-possession. Yet as uncertainty takes over rhetorically, there is an unabashed flair in the form.

The book pivots between two locations on stage – here, a woman addresses the audience about her life, her child, her lover – and there, a “chorus” of children announces what they have been told of the world. For the children, it is almost always something/someone other who imposes the terms of definition and understanding. For the woman/mother, the challenge is to find some aspect of living that might indicate there is more to it than imposition – somewhere in the solitary space between imposing and being imposed upon.

CHORUS

What’s wrong? we ask.

To keep from answering, they keep reading.

The Book of Illusions,

The End of Illusion,

and On Not Being Able to Sleep.

But we know more than they think.

It’s true they love us,

more than anything,

and their hands in the Easter air look loving

moving the eggs to their places.

They hide them over and over again –

under the lion mask,

in the brim of the policeman’s hat –

so we’ll think there’s plenty.

Often the dye seeps into the cracks

and stains the white of the egg,

but so what.

A little salt and it’s sweet again.

It is clear from the outset that the poems’ lines have been “written” for their speakers and that the main impulse is performative. In the opening poem, “Scavenger Hunt,” the woman asks, “Can I write a play of it, / starring Father of Styrofoam! / Mother of Glass!” The audience must pick up the pieces and see if anything adds up. The audience, then, is positioned closer to the children than the adult speaker. Barnett has an unabating redemptive (and even sententious) impulse, and she knows it, and guards herself against it with strict adherence to a compensating, regulated expression. The tussle between these tensions, habits, hunches and new desires produces the unique sounds of these often starkly phrased poems.

UNDERGROUND SUBLIME

I heard myself calling into

the crowded subway,

hold the doors!

Everything I cared about

was already inside

and the voice I discovered then

is like the siren now outside

my window, the manhole cover

knocking again and again

as cars drive across it,

voice of the nights’

adrenaline crow

calling from the rooftops

into avenues of air.

The poem speaks in the wake of its shrill cry, apparently completely explicable in its intent, and yet within it, just as within the moment it describes, something wilder resists comprehension. Or acceptance. “Everything I cared about” could be the child or someone or something else. The fearful cry is yet another embedded sound of the city. The Game of Boxes performs like an urban, more streetwise version of Louise Glück’s The Wild Iris or Meadowlands, the alternating speeches contending with one another, the separate characters dealing with determinate forces and wanting to be recognized.

CHORUS

Everyone asks what we’re afraid of

but we aren’t supposed to say.

We could put loneliness on the list.

We could put this list on the list,

its infinity. We could put infinity down.

Who knows why we’re here, it’s a “mystery.”

We’re getting older,

and when no one’s watching

we climb right into it.

In part one, the mother describes her mission (again, responsibility entails inquiry) and her solitariness (“I draw all night / to distract my boy / from the greater deletions –“) while the chorus of children intuits the qualities of the actual (“who mothers our carrying-on, / carrion comfort sleeping / eyes open, who mothers us?”). The audience has the privilege of perceiving the mutual unknowingness – and embracing it. The poet’s delicate call for empathy is cravenly lovely. In part two, a 24-part soliloquy, the woman addresses the man. Thrall coexists with repulsion. Between them, a bland but concise assessment:

xvii.

Sometimes he’s everything to me:

yesterday, tomorrow, regret and shame.

And sometimes he’s nothing to me,

an old cushion on an old couch:

a pin-cushion:

something I think I can replace.

Barnett is allowing the language to slouch. There is a muted interrogation of motive through the poems – motive, in fact, is the poems’ obsession. Therefore, the poet selects a mode of phrase-making that resists the overreach and quotability. There is, of course, a danger here, namely a withering of the reader’s attention. It’s a weary aria, full of caution, misgivings, parceled indulgence and stingy praise. But the section’s exactitude and pared-down responses ultimately win. I believe it all because the rather skeletal expressiveness registers as the inevitable alternative.

Part three (“the modern period”) is intended as an outbound portal for the main speaker. Her considerations billow out somewhat; she makes her way through the city.

SOLILOQUY, ii.

I could not be, even now, just particles of mist

but I might wish to be –

I couldn’t be mist because mist

is airborne, mist doesn’t wear black

leggings and dirty up so many pages.

No mother is only mist.

Even my child tells me I’m scared and

in the same breath says I’m scared of

nothing. Depends on how you define “nothing” –

I think it’s a little shard of the whatnot

I keep trying to name.

An empty glass can be said to hold nothing.

Perhaps I was mist in a previous life,

maybe that’s why I can’t understand

these instructions. Or perhaps I’ll

be, in my next life, mist. When did it

get so mysterious? This isn’t me speaking

but the old gentle hiss of a slow glass

ship in a bottle on the sea.

Catherine Barnett dares to “dirty up” her poems in The Game of Boxes with the blear of ignorance. “A little shard of the whatnot” sticks in her throat and makes it hard – no, necessary – to disavow the more applied observances of her earlier work (which is still moving and surprising even after so many reads). Like the woman in her newer poem “Still Life,” it looks like Barnett has “already given herself to the world.”

[Published by Graywolf Press on August 7, 2012. 88 pages, $15.00 original paperback]

C Barnett’s Poetry

I was a student of Prof. Barnett and have admired her work since I met her. I think this is the most insightful commentary I have seen about her writing. Her first book continues to give me shivers. It is very collected in its way but also fragile, or it suggests something fragile underneath. The newer poems are a kind of opera with arias and chorus. The poet stays backstage. I’m glad to have discovered your reviews.