Stefan Zweig began writing his autobiography, The World Of Yesterday, in 1934, the year he departed Vienna to escape the Anschluss and Nazi persecution of the Jews. After a brief stay in England and a longer period spent in Manhattan and Ossining, New York, Zweig and his second wife Lotte moved to Petrópolis in Brazil in 1941. Just hours before the couple committed suicide on February 22, 1942, he posted the manuscript to Sweden where it was published later that year.

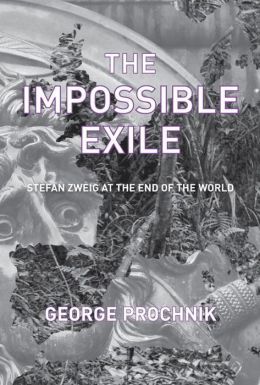

George Prochnik says that The World of Yesterday “was a constant reference point, inspiration, and foil” during the writing of The Impossible Exile, his narrative on the uprooting of Zweig’s world. Prochnik also notes the memoir’s “nostalgia, its flaws, and its willful illusion.” Nevertheless, The World of Yesterday poignantly expresses the despair suffered by a generation with no alternative but to witness the sudden destruction of their aspirations.

George Prochnik says that The World of Yesterday “was a constant reference point, inspiration, and foil” during the writing of The Impossible Exile, his narrative on the uprooting of Zweig’s world. Prochnik also notes the memoir’s “nostalgia, its flaws, and its willful illusion.” Nevertheless, The World of Yesterday poignantly expresses the despair suffered by a generation with no alternative but to witness the sudden destruction of their aspirations.

The poignancy did not impress Hannah Arendt. In her 1948 takedown of Zweig and his autobiography, she mocked him for a craven yet oblivious attachment to Hapsburg culture, literary careerism, and a failure to use his celebrity to speak out against Fascism:

“Concerned only with his personal dignity, he had kept himself so completely aloof from politics that, in retrospect, the catastrophe of the last ten years seemed to him like a lightning bolt from the sky, as if it were a monstrous, inconceivable natural disaster … Not one of his reactions during all this period was the result of political convictions; they were all dictated by his hypersensitivity to social humiliation. Instead of hating the Nazis, he just wanted to annoy them. Instead of despising those of his coterie who had been gleichgeschaltet, he thanked Richard Strauss for continuing to accept his libretti.. Instead of fighting, he kept silent, happy that his books had not been immediately banned … This could not reconcile him to the fact that his name had been pilloried by the Nazis like that of a ‘criminal,’ and that the famous Stefan Zweig had become the Jew Zweig.”

At pains throughout his book to maintain an empathic but critical perspective, Prochnik states, “Stefan Zweig falls into the category of those who incarnate the enchantments and corruptions of their environment.” The eight-year exile may be Prochnik’s proximate topic, but it is through the self-divisions and obsessions within Zweig that we begin to understand the tragedy of his unique case. Prochnik’s essayistic and often discursive approach allows him to speculate – an apt technique since Zweig’s complexities resist snappy analysis. He resembles both the narrator and the subject of his novella Chess Story:

At pains throughout his book to maintain an empathic but critical perspective, Prochnik states, “Stefan Zweig falls into the category of those who incarnate the enchantments and corruptions of their environment.” The eight-year exile may be Prochnik’s proximate topic, but it is through the self-divisions and obsessions within Zweig that we begin to understand the tragedy of his unique case. Prochnik’s essayistic and often discursive approach allows him to speculate – an apt technique since Zweig’s complexities resist snappy analysis. He resembles both the narrator and the subject of his novella Chess Story:

“All my life I have been passionately interested in monomaniacs of any kind, people carried away by a single idea … people, as unworldly as they may seem, burrow like termites into their own particular material to construct, in miniature, a strange and utterly individual image of the world.”

Zweig’s monomania was writing itself. Beginning with Forgotten Dreams (1900), he produced thirty-seven works of prose fiction, mainly novellas, and three collections of short stories. He also wrote sixteen biographies and histories and three plays. As perhaps the most popular author of his era, he was an affluent celebrity whose work was translated during his lifetime into twenty-nine languages.

“Stefan Zweig just tastes fake. He’s the Pepsi of Austrian writing,” quipped Michael Hofmann in his 2010 London Review of Books essay on The World of Yesterday. “He is the one whose books made films – 18 of them, and that’s the films, not the books (which come in at a stupefying 38). It makes sense: these are hypothetical and bloodless and stiltedly extreme monuments and monodramas for ‘teenagers of all ages’, as someone said.”

“Stefan Zweig just tastes fake. He’s the Pepsi of Austrian writing,” quipped Michael Hofmann in his 2010 London Review of Books essay on The World of Yesterday. “He is the one whose books made films – 18 of them, and that’s the films, not the books (which come in at a stupefying 38). It makes sense: these are hypothetical and bloodless and stiltedly extreme monuments and monodramas for ‘teenagers of all ages’, as someone said.”

But there is nothing fake about Pepsi. It simply tastes like itself with no variation glass after glass. Such is the case with Zweig’s prose fiction, each novella built on a rigid armature, the main characters (divided and in conflict with themselves) proceeding directly to their fates as determined by their passions, illusions, and limits.

His popularity alone is enough to cause critics to sniff at him, though there is also Zweig’s disinterest in (or incapability for) developing a penetrating stylishness or incorporating philosophical ideas. But there was more. Unresponsive to the rise of literary modernism, his narrators are obsessed storytellers in the mode of Hardy, Ford and Conrad. Despite the decay of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he seemed too wedded to its values and the dream of a “universal culture” caffeinated by European table and hotel lobby conversation.

“The existential enigma has disappeared behind political certitude,” wrote Milan Kundera in his essay “Somewhere Behind.” Zweig’s squeamishness over political assertion may have incensed Arendt and the bland force of his work may offend Hofmann, but Zweig never took his eye (or nib) off the enigma. Prochnik incorporates that stubborn, generous contemplation into his narrative. Drawing from a wide range of sources, he writes with a tone of familiarity informed by his own family’s experiences in exile. He registers Zweig’s dodgy behavior while understanding what Zweig meant at the opening of his autobiography: “Never … has any generation experienced such a moral retrogression from such a spiritual height as our generation has.”

“The existential enigma has disappeared behind political certitude,” wrote Milan Kundera in his essay “Somewhere Behind.” Zweig’s squeamishness over political assertion may have incensed Arendt and the bland force of his work may offend Hofmann, but Zweig never took his eye (or nib) off the enigma. Prochnik incorporates that stubborn, generous contemplation into his narrative. Drawing from a wide range of sources, he writes with a tone of familiarity informed by his own family’s experiences in exile. He registers Zweig’s dodgy behavior while understanding what Zweig meant at the opening of his autobiography: “Never … has any generation experienced such a moral retrogression from such a spiritual height as our generation has.”

Zweig’s first wife, Friderike Maria von Winternitz (nee Burger), who knew him as well as anyone, wrote to him in 1930, “You have let few people get close to you. You lock yourself up within yourself so completely. Your writings are only one third of you: and no one has managed to discover the essential you in them, which might explain the other two-thirds.” Prochnik’s gaze at Zweig’s exile is essentially an effort at discerning a whole self in the process of disintegration – while allowing for Zweig’s “increasing uncertainty about where his integral self abided.”

To his friend Jules Romains, Zweig wrote, “My inner crisis consists in that I am not able to identify myself with the me of my passport, the self of exile.” To this, Prochnik adds, “Another way of framing Zweig’s dilemma would be to say that the state of exile made Zweig feel trapped in someone else’s narrative. And the falsity of this position was far worse than the prospect of complete erasure from the world.”

To his friend Jules Romains, Zweig wrote, “My inner crisis consists in that I am not able to identify myself with the me of my passport, the self of exile.” To this, Prochnik adds, “Another way of framing Zweig’s dilemma would be to say that the state of exile made Zweig feel trapped in someone else’s narrative. And the falsity of this position was far worse than the prospect of complete erasure from the world.”

True, one makes allowances for Zweig. But allowances are granted as well for scores of western writers whose political enthusiasms for Communism led to benighted views of Stalin’s murder-state. We forgive Pound’s treason, we forgive Eliot’s and Stevens’ anti-Semitism. Alternately moving and quizzical, Prochnik’s book may not tell us anything new about Zweig, factually speaking. But it shows us a way beyond allowances toward a tremulous vision of Zweig’s moment.

[Published by Other Press on May 6, 2014. 390 pages, $27.95 hardcover]

Hannah Arendt’s essay “Jews in the World of Yesterday” may be found in her Reflections on Literature and Culture (Stanford University Press, 2007)

Stefan Zweig’s suicide note (translated from the German):

“Before parting from life of my free will and in my right mind I am impelled to fulfil a last obligation: to give heartfelt thanks to this wonderful land of Brazil which afforded me and my work such kind and hospitable repose. My love for the country increased from day to day, and nowhere else would I have preferred to build up a new existence, the world of my own language having disappeared for me and my spiritual home, Europe, having destroyed itself.

But after one’s sixtieth year unusual powers are needed in order to make another wholly new beginning. Those that I possess have been exhausted by long years of homeless wandering. So I think it better to conclude in good time and in erect bearing a life in which intellectual labour meant the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on earth.

I salute my friends! May it be granted them yet to see the dawn after the long night! I, too impatient, go on before.”

Re Zweig

Mr Prochnik’s study sounds excellent; it makes me wish I were more familiar with Stefan Zweig’s work. Thank you for such a fine review. One can see the point Zweig makes in his suicide-note. One can even sympathize. After a certain age the search for the “missing two-thirds” (the ex-wife probably nailed it) would require some unusual powers. Although of course an overly-developed third, i.e. his writing life, might have just been camoflage for an empty blind – the discovery of which and its acceptance would also require unusual powers. The monomania thing sounds a bit disturbing though. (Readers might Cf. Season 2 of the BBC’s “The Trip to Italy”, with our 2 heroes Steve Coogan & Rob Brydon — which also wanders in this mid-life “dark woods”.)