For a good laugh and a sigh, Carlos Rojas likes to repeat a piece of advice he got from Jose Manuel Lara (1914-2003), the founder of Planeta, Spain’s biggest media empire. “Carlos, you and the likes of you are a bunch of pedantic dudes, who know just about four things,” said Lara. “Therefore you believe that readers should know at least two things in order to resemble you. What you do not want to understand is that readers do not know anything. The day you comprehend such evident certainty you will write wonderful novels that will sell like bread, and all of us will strike it rich.”

The tyrannical Lara became notorious for spending 6,000,000 pesetas on flowers for his fiftieth wedding anniversary, but Rojas never produced a mainstream money-maker for the machine. Born in Barcelona in 1928, Rojas vocally opposed the “realistic” novel of the post-war period because, according to Cecelia Castro Lee, “it did not respond any longer to the aesthetic and intellectual needs of readers. Instead, he promoted a more imaginative, artistic, intellectual, and universal novel.”

The tyrannical Lara became notorious for spending 6,000,000 pesetas on flowers for his fiftieth wedding anniversary, but Rojas never produced a mainstream money-maker for the machine. Born in Barcelona in 1928, Rojas vocally opposed the “realistic” novel of the post-war period because, according to Cecelia Castro Lee, “it did not respond any longer to the aesthetic and intellectual needs of readers. Instead, he promoted a more imaginative, artistic, intellectual, and universal novel.”

While experimenting with technique, Rojas interrogates history, cultivates universal themes, and maintains an allegiance to myth, folklore, and fabulism. His twenty novels have earned many national literary awards but are barely known in America. His first novel, De barro y esperanza (Of Mud and Hope), was published in 1957. In 1973, the critics awarded him the Planeta Prize for Azaña, which firmly established his reputation in Spain. Since 1960, he has taught Spanish literature at Emory University. He has also written books on art history and on the works of Ortega, Unamuno and Machado. Since 1978, he has worked steadily as a visual artist.

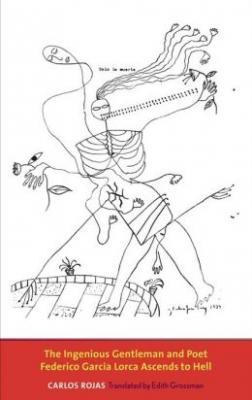

The popular novels known as his Sandro Vasari Trilogy are considered his signature works. The second title in the series, the Nadal prize-winning The Ingenious Gentleman and Poet Federico García Lorca Ascends to Hell, first published in 1980, has now been translated by Edith Grossman. The narrative is spoken by Lorca as he awaits judgment in hell. The dead exist here in solitude, each sitting in a seat in his or her individual auditorium while the scenes of one’s life replay on stage:

“Death is a solitary confinement where each of the dead has an empty theater along the spiral of hell. That is the tragedy of immortality before the spectacle of what has been lived: not ever being able to share it with anyone, as if I were the only man who has lived in vain on earth. Or just the opposite, as if I were the only dead man in the world.”

In both his works and his conversations, Lorca had said that he regarded death as the snuffing out of individual consciousness. But in Rojas’ hell, he says, “I never could have imagined, as perhaps no one in the world ever has, that death was in fact a sentence to be precisely who we were, fully conscious of ourselves. through all time and perhaps beyond days and centuries.” But now fully conscious, he watches the scenes of his life and witnesses complexities he had not seen before. His mind is still deeply moral — but the world may be otherwise by its nature.

Lorca was murdered by firing squad outside the city of Granada on August 19 or 20, 1936. He had been arrested by the fascists on August 16 at the house of his friends, the Rosales family, and taken by car to jail at the Civil Government building. It has been supposed that during Lorca’s incarceration, Governor Valdés was awaiting word from Madrid on what to do with his prisoner. Although sleuthing by researchers has uncovered certain facts about Lorca’s final hours, the sites of his murder and burial (if there was one) are unknown.

But the Lorca of Rojas’ novel does not speak for the purpose of illuminating such grim details. He begins with “The Spiral,” sometimes referring to himself in the third person: “Death is not repose or forgetting but the eternal presence of what you have lived in the world and in your soul. You might say that the poet’s obligation is to invent the past that men forget, and foresee the inverted image of all the future, on earth and on this spiral.” This, of course, is also Rojas’ obligation, and he swirls these things together in a bracing, scorching, obsessive manner.

Lorca’s memories soon begin their repeat performances on stage, beginning with his final lunch in Madrid, a long conversation with his friend, Rafael Martínez Nadal, who would take him to the train station for the fateful trip to Granada. All sorts of notions flit through the narrative, including impressions of paintings he had seen in the museum, Velázquez, Monet. Then, in chapter two, “The Arrest,” Señor Ruiz Alonso denies having informed on Lorca, or rather, admits he did so but for unavoidable reasons. All the while, we understand that somehow Lorca is preparing for his trial. Will he be acquitted, and if so, for what sins, what crimes?

Lorca’s memories soon begin their repeat performances on stage, beginning with his final lunch in Madrid, a long conversation with his friend, Rafael Martínez Nadal, who would take him to the train station for the fateful trip to Granada. All sorts of notions flit through the narrative, including impressions of paintings he had seen in the museum, Velázquez, Monet. Then, in chapter two, “The Arrest,” Señor Ruiz Alonso denies having informed on Lorca, or rather, admits he did so but for unavoidable reasons. All the while, we understand that somehow Lorca is preparing for his trial. Will he be acquitted, and if so, for what sins, what crimes?

He says, “I perceive with dismay the close correspondence between dreams and eternity in the warp where life and death are interwoven and become identified. I would also affirm, though I can confess this certainty only to myself, that literature is the closest key to this labyrinth where the living and the dead are commingled.”

If death was Lorca’s grand obsession, and if, as he says here, his elegy to Ignacio Sánchez Mejías is “a thirteen-line poem that was the premonition of everything you see now,” then is Lorca responsible for what must now recur in hell, since it is he who first created its image? Lorca’s “acquittal” arrives — but I must let you discover through what agency it comes.

Rojas is known for his adventures with ekphrasis, intertextuality, and metafiction – but his touch is light, leavened with dark humor. The Ingenious Gentleman is as much a meditation on literature as a troubled and troubling dream of the death of Lorca. The dialogue between Lorca and Governor Valdés, dying from cancer, is unforgettably creepy. And then, the ride outside of the city with three other prisoners draws out the deadly moment. The Buick breaks down, fate hangs in the air.

Rojas is known for his adventures with ekphrasis, intertextuality, and metafiction – but his touch is light, leavened with dark humor. The Ingenious Gentleman is as much a meditation on literature as a troubled and troubling dream of the death of Lorca. The dialogue between Lorca and Governor Valdés, dying from cancer, is unforgettably creepy. And then, the ride outside of the city with three other prisoners draws out the deadly moment. The Buick breaks down, fate hangs in the air.

This novel carries the weight of conscience even as it makes way for all kinds of metaphysical speculation. The spirits of Cervantes and Dante thrive here. Rojas’ restless, indirect style, always receptive to the next thought or image, is propelled by a desire to help us clarify a question that haunts us still:

“Can the inability to understand one another while they breathe in this world be the fate of all men?”

[Published by Yale University Press on April 16, 2013. 224 pages, $24.00 hardcover]

Bread

I love the image of novels selling like bread.

Other

I love the image of men breathing in this world trying to understand each other.

On Duende

Readers might find this link to a Raphael López-Pedraza essay on Duende useful: http://www.jungatlanta.com/articles/Duende.pdf