H. G. Adler’s The Journey begins with a three-page “Augury.” When Peter Filkins discovered a copy of Die Reise in Schoenhof’s Foreign Language Bookstore in Harvard Square in 2002, he read the introductory paragraph and immediately determined to translate the novel:

“Driven forth, certainly, yet without understanding, man is subjected to a fate that at one point appears to consist of misery, at another of happiness, then perhaps something else; but in the end everything is drowned in a boundlessness that tolerates no limit, against which, as many have said, any assertion is a rarity, an island in a measureless ocean. Therefore there is no cause for grief. Also, it’s best not to seek out too many opinions, because, by linking delusions and fears to which we are addicted, strong views keep you constantly drawn to what does not exist, or even if it did, would seem prohibited. So you find yourself inclined to agree with this or that notion, the emptiness of a sensible or blindly followed bit of wisdom, until you finally become aware of how unfathomable any view is, and that one is wise to quietly refrain from getting too involved with the struggles to salvage anything from the rubbish heap, life’s course demanding this of us already.”

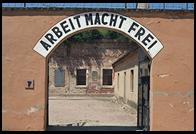

The Journey is categorized as a “Holocaust novel,” as it should be. The narrative tracks the fate of an elderly doctor, Leopold Lustig, and his family as they are rounded up in “Stupart” (a city resembling Prague), sent to “Ruhenthal” (a walled town turned into a concentration and transit camp recalling Thereisenstadt), subjected to a parallel existence of deprivation and surreal dislocation, and condemned to die. But the “augury” tells us at once that while the world may be divided into aggressors and victims for the purpose of structuring history, the experience and recognition of one’s place in that world is a more complex and uncertain matter. The lyricism both appeals to some unexercised part of our understanding (though we understand once that part is sparked by such language) and deters the reader looking for a conventional reading experience. The narrative voice of The Journey shifts its identity and tone at will – such that the reader who prevails must subject oneself to the book’s headstrong linguistic urges and the uncomfortable awareness “of how unfathomable any view is.”

The Journey is categorized as a “Holocaust novel,” as it should be. The narrative tracks the fate of an elderly doctor, Leopold Lustig, and his family as they are rounded up in “Stupart” (a city resembling Prague), sent to “Ruhenthal” (a walled town turned into a concentration and transit camp recalling Thereisenstadt), subjected to a parallel existence of deprivation and surreal dislocation, and condemned to die. But the “augury” tells us at once that while the world may be divided into aggressors and victims for the purpose of structuring history, the experience and recognition of one’s place in that world is a more complex and uncertain matter. The lyricism both appeals to some unexercised part of our understanding (though we understand once that part is sparked by such language) and deters the reader looking for a conventional reading experience. The narrative voice of The Journey shifts its identity and tone at will – such that the reader who prevails must subject oneself to the book’s headstrong linguistic urges and the uncomfortable awareness “of how unfathomable any view is.”

Hans Günther Adler (1910-1988) first attracted the notice of English readers with Theresienstadt 1941-1945 (1955), his study written just after the end of the war. Born in Prague, Adler and his wife spent more than two years in the camp; his wife and her mother later died in Auschwitz. Adler was sent to Niederorschel, a camp near Buchenwald, to work in a factory turning out metal sheeting for the Luftwaffe. Liberated by the Americans from the Langenstein-Zwieberge camp, he returned to Prague but emigrated to London in 1947. Despite having written twenty-six books including six novels, poetry, history, philosophy, and hundreds of essays on the Holocaust and other topics, “his name hardly ever appears in the standard works on the Holocaust,” notes Peter Filkins. “How could this have happened? What is it about Adler or his work that could have led to such a demise?” His obscurity persists. For instance, there is no Wikipedia page for Adler (just as until recently there was no such page for Irène Némirovsky). Two of his novels have never been published.

Hans Günther Adler (1910-1988) first attracted the notice of English readers with Theresienstadt 1941-1945 (1955), his study written just after the end of the war. Born in Prague, Adler and his wife spent more than two years in the camp; his wife and her mother later died in Auschwitz. Adler was sent to Niederorschel, a camp near Buchenwald, to work in a factory turning out metal sheeting for the Luftwaffe. Liberated by the Americans from the Langenstein-Zwieberge camp, he returned to Prague but emigrated to London in 1947. Despite having written twenty-six books including six novels, poetry, history, philosophy, and hundreds of essays on the Holocaust and other topics, “his name hardly ever appears in the standard works on the Holocaust,” notes Peter Filkins. “How could this have happened? What is it about Adler or his work that could have led to such a demise?” His obscurity persists. For instance, there is no Wikipedia page for Adler (just as until recently there was no such page for Irène Némirovsky). Two of his novels have never been published.

There are several reasons for his invisibility. He wrote in German, but German publishers had virtually no interest in Holocaust-related fiction in the 1950s. Filkins observes that only four novels about the Holocaust written in German by survivors were published in the 1950s. (The hesitation is widespread. Aharon Appelfeld, who writes in Hebrew and has published eleven Holocaust-colored novels, calls himself “the only author in Israel who is dedicated to writing about the Holocaust.”) We have already noted Adler’s prose style, unmarketably modernist for an audience that extols Elie Wiesel’s Night. The Journey alarms readers not only because of the brutality portrayed, but for the cultivated weakness of its characters. Just as Franz Kafka had introduced the figure who is as thoroughly guilty as he is innocent (guilty not only of being “other,” but of being innocent), Adler’s characters are drawn as ingenuous but integral to the procession of their punishments.

As the Lustig family bundles its belongings per orders of the authorities, we read the following:

“Everything is packed tight, and there’s wisdom in bundling everything together in defiance of what’s ordered, because one’s possessions are themselves an expression of human nature, as only humans can possess something. But possessions are also obsessions, and soon they will be more powerful than those who possess them, since things reveal how they came to be possessed.”

The narrator is disinclined merely to describe the rueful and pathetic scene. He must also inject a hyper-knowledge which, if it were not lyrically convincing, would sound supercilious. When do those possessions become more powerful? Upon confiscation, as evidence of the greed of possessing and the liquidation of prior owners. Yet both parties, say the narrator – the Lustigs and the authorities – obsess over these things. Adler, of course, never confuses or elides the two modes of possession. If anything, his novel plows a deep trench of irony into which the reader tumbles now and then, wearied by its unrelenting, rutted perspective. Adler’s point is that a third mode of seeing must be salvaged from the horrific evidence based on neither innocence nor murderousness. The view is embodied in the combined voices of The Journey.

Soon the Lustigs must adapt to life in Ruhenthal. “At midday, when there’s an hour’s rest from work, the guards change shifts. These soldiers also have their orders to take you back to Ruhenthal early in the evening and hand you over to the guards after carefully counting you. Orders alone artificially hold you together and in a few hours divide you again, it all taking a short while. Only a set of gestures and understood signs unites you, there being no way to relate to one another on a deeper level; everything that transpires happens in an inhuman network that consumes all of us.”

Soon the Lustigs must adapt to life in Ruhenthal. “At midday, when there’s an hour’s rest from work, the guards change shifts. These soldiers also have their orders to take you back to Ruhenthal early in the evening and hand you over to the guards after carefully counting you. Orders alone artificially hold you together and in a few hours divide you again, it all taking a short while. Only a set of gestures and understood signs unites you, there being no way to relate to one another on a deeper level; everything that transpires happens in an inhuman network that consumes all of us.”

The voice is speaking almost reasonably to the victims, as if to calm them. Of course this is all comprehensible! In the “Augury,” the speaker could have been describing any of our lives, our willingness at any moment to follow “the emptiness of a sensible or blindly followed bit of wisdom.” The same occurs in the passage above, the final sentence of which sounds like a growling definition of post-modernism. Perhaps this is what annoys some readers about Adler: he refuses to enshrine his victims, to make them exceptional. Peter Filkins told me in an email note that “Adler’s intricate and elusive artfulness would have made the reception of The Journey all the more hostile, which partially explains the long delay in its initial publication, and its almost immediate disappearance when it was published in 1962, twelve years after it was written.”

The desperation to explain the extreme lies behind the variety of techniques employed by Adler in The Journey — which is also a refusal to conform to literary norms that would make the narrative too palatable. The narrative voices represent the guilty and the dead, the authorities and the perpetrators, detached bystanders and engaged commentators. One hears the menacing tones of oppressors and the questioning of deportees. Filkins refers to The Journey as a kind of “tone poem.” The continuum of time is disrupted. The language may be highly figurative, then suddenly lyrical. Details are acutely observed. Impressions flow together. Then, a single image persists. The characters are not “developed” in the traditional sense, since they are being reduced by their circumstances. Their function is to scandalize the reader – whose notions of normalcy are challenged since they resemble those of the Lustig family:

“On a small, albeit sudden surprise can upset the inertia of one’s feeling, which in themselves always want to cling to normalcy, since within that exists a protection against overwhelming suffering. It’s true, whoever needs to protect himself ends up feeling doubly disturbed at any change, for normalcy is invoked as a means to scare away loneliness. Yet because normalcy doesn’t find the truth to be sweet, truth always wins out, thus normalcy can never be certain that it will continue to exist. One may always like to think of it as reliable, but it is clear to all that though it may be nurtured for long periods of time, in the end it always abandons human beings without fail.” Normalcy entails amnesia. Adler’s voice represents the extended jittery moment when memory rises into metaphor.

Aharon Appelfeld was once asked to describe the Jewish psyche as a product of centuries of persecution. He answered, “From one side you have the character that is neurotic, anxious, and so on, but from the other side you have philosophy, religion, morals. And how were these two things combined? This is really the Jewish phenomenon. Being a minority, but still believing in your own values.” Elsewhere, he insisted that “artistic writing is not a process of healing. It’s extending your personality. It’s enriching your personality with different metaphors and symbols.” For Adler as novelist, anxiety is cultivated through the surprises and disorientations of his technique, leaving the moral dimension to the force of irony. This integrated expression extends a personality damaged by grief but empowered by daring language. Survival necessitates reinventing one’s life, not reconstructing it, since the old sensibilities no longer pertain.

Adler’s method and Appelfeld’s comments put the reputation of “witnessing” as an artistic foundation into question. Appelfeld remarked in an interview, “The testimony tends to be a form of psychological release rather than coping. The testimonies create the right void for forgetfulness. The testimony doesn’t create circles and doesn’t reverberate inside.” Obviously, the collection of testimonies has been central to worthy projects such as Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation. But Appelfeld’s comments help us understand why Adler could not risk adding to “the right void.”

There are times when Adler simply loses his fictional grip and groans or rants among the abstractions. “In the name of justice, injustice is installed, defying the condemnations that want to destroy the visible signs of greed. Yet the monuments have long since superseded human power with their own power …” At times, it is not the bleak tone that seems indulgent but its timing in the text: “Existence is all that remains, an almost incomprehensible collection of the detritus left over.” In other instances, his ironies are repetitive or banal – a danger arising from language that intentionally swoops between lyricism and a reckoning that sounds bland in comparison. But when the aim of the work is an awakening, it is absurd to expect a lullaby. Adler is willing to risk any phrase or gesture if it has the potential to prod – including the macabre. “The natural decomposition of the body,” he writes, “is reduced to a manageable amount of time. This indeed means no food for the worms, but they can apply at the unemployment office for a new and better position, such as agriculture or earthworks.”

This is a story about a family. Their story doesn’t progress so much as back them into the inevitable, and their powerless lives tell us virtually nothing. In the end, Lustig’s son Paul survives: “Whatever happened, it’s fortunate that Paul has been allowed to remain alive in his body and has not been reduced to ashes … The direction has been lost, any way forward leads only to nothing, which is why nothing moves forward … No other existence is possible, it doesn’t even attempt to assert itself; what is not itself is eradicated, done away with, no longer accepted, for it cannot be withstood; it is tossed away.” It’s been said that many Jews regard the Holocaust as their Passion Play, a source of redemption. But Adler would have none of it. His revenge on negation was to make the living eat of it, know its bitterness, and admit that the discovery of the actual is more critical now than the relief of normalcy.

[Published November 4, 2008 by Random House, 352 pp., $26.00. Peter Filkins teaches writing and literature at Bard College at Simon’s Rock in Great Barrington, MA.]

H’G. Adler’s The Journey

Just one small correction — H.G. Adler’s monumental work, Theresienstadt 1941-1945: das Antlitz einer Zwangsgemeinschaft, Geschichte, Sociologie, Psychologie (Tubingen, 1955) has never been translated into English.

Paul Howard Hamburg

Librarian for the Judaica Collection

UC Berkeley