“This hard-boiled stuff — it’s a menace.”

— Dashiell Hammett, 1950

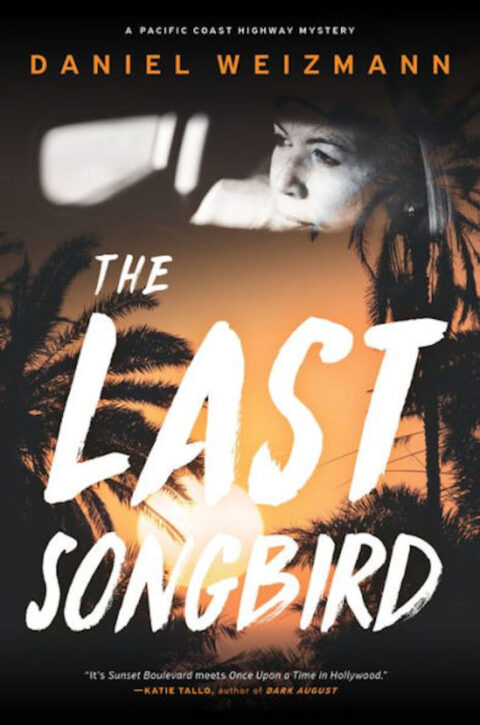

At the center of Daniel Weizmann’s new wave noir novel, The Last Songbird, is Adam “Addy” Zantz, a nebbish-like Lyft driver and would-be songwriter who, at moments opportune or not, can’t stop semi-composed lyrics from popping into his head. As he drives through L.A.’s streets, mean as well as meaningless, he obsesses about what might have been. He’s unable to come to terms with his ex- and former songwriting partner, having left him for a more professional songwriter-boyfriend. Nor can he relinquish his attachment to Annie Linden, a 73-year old former celebrity singer-songwriter (think Stevie Nicks crossed with Joni Mitchell), still worshipped by her fans, whom Adam drives to and from her Malibu home no matter the time of day. When her body is washed ashore in Hermosa Beach, the wrong person is arrested, and Adam feels he owes it to Annie to find the actual killer, as well as honour a request she made that he find something — Adam doesn’t yet know what — from her past. What keeps him on this two-fold case is not only his connection to a woman he regards as a kindred, if self-centered, spirit, but because she was, on the basis of a demo he once played for her in his car, the only person ever to express an appreciation for his potential as a songwriter.

Something of a Harold and Maude type of relationship, perhaps, but as any all-night cab driver can attest, unlikely fly-by-night friendships and adventures are commonplace in that line of work. Driving the graveyard shift in San Francisco in the late 1960s, every night, for me felt like an adventure, stopping only just short of what Zantz experiences. Maybe it was the drugs, at the time de rigueur for driving into the early morning light, enhancing everything, not least the paranoia that insisted on riding shotgun, on the lookout for the Zodiac or some other encrazed individual with a grudge against cabbies. Although more fleeting than Zantz’s obsession with Annie, I remember falling for an older French woman — probably no more than in her early 30’s — straight out of Jacques Demy’s Model Shop — who read palms in Fisherman’s Wharf to pay for her and her daughter’s return to Paris. Fresh out of San Francisco State, I willingly contributed to her traveling expenses. Driving a cab is like that, the sort of job, whether permanent or precarious, that attracts a certain type, the sort who’d otherwise be writing poetry or a novel, or, as in Adam’s case, songs, and who can’t help but view their taxi as their personal theater, sometimes of the absurd, at other times of cruelty, depending on their fare, and on the way the cultural winds happen to be blowing on that particular day. It’s also the perfect job for someone investigating the culture. After all, in that line of work, as Weizmann demonstrates, contact with the world in all its sleazy glory is unavoidable, thrusting its presence on you whether you seek it out or not.

Something of a Harold and Maude type of relationship, perhaps, but as any all-night cab driver can attest, unlikely fly-by-night friendships and adventures are commonplace in that line of work. Driving the graveyard shift in San Francisco in the late 1960s, every night, for me felt like an adventure, stopping only just short of what Zantz experiences. Maybe it was the drugs, at the time de rigueur for driving into the early morning light, enhancing everything, not least the paranoia that insisted on riding shotgun, on the lookout for the Zodiac or some other encrazed individual with a grudge against cabbies. Although more fleeting than Zantz’s obsession with Annie, I remember falling for an older French woman — probably no more than in her early 30’s — straight out of Jacques Demy’s Model Shop — who read palms in Fisherman’s Wharf to pay for her and her daughter’s return to Paris. Fresh out of San Francisco State, I willingly contributed to her traveling expenses. Driving a cab is like that, the sort of job, whether permanent or precarious, that attracts a certain type, the sort who’d otherwise be writing poetry or a novel, or, as in Adam’s case, songs, and who can’t help but view their taxi as their personal theater, sometimes of the absurd, at other times of cruelty, depending on their fare, and on the way the cultural winds happen to be blowing on that particular day. It’s also the perfect job for someone investigating the culture. After all, in that line of work, as Weizmann demonstrates, contact with the world in all its sleazy glory is unavoidable, thrusting its presence on you whether you seek it out or not.

All of which is to say, what might seem far-fetched in the light of day can be ghostly real once the sun goes down, and you’re at the mercy of the laws of chance. Because once all those upstanding citizens go home from their jobs or entertainments of choice, and the streets fill up with the denizens of the night, anything can happen. It simply goes with the territory. And this is what Weizmann so ably captures, placing Addy in a world just a step outside his comfort zone and comprehension, subject, for better or worse, to the winds of fate. Consequently, The Last Songbird can be added to that swathe of crime novels, now a sub-genre all its own, that focus on taxi cab drivers, such as Lee Durkee’s The Last Taxi Driver, Jack Clark’s Nobody’s Angel, Fuminor Nakamura’s The Boy In the Earth, and others. Not to mention a film like Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. And who can forget the anarcho-syndicalist taxi cab driver, played by Elijah Cook Jr. in Wim Wenders’ film Hammett, with a screenplay written by, amongst others, noirists Joe Gores and Ross Thomas.

But it seems like it takes more than one sub-genre to venture into the depths of present day Los Angeles. Certainly Weizmann’s first-person narrative could also be categorised as Jewish-noir. Born in Israel during the 1967 Six Day War and the Summer of Love, then arriving in Hollywood as an infant, Weizmann litters his novel with Jewish characters and vernacular. No so much in the vein of Jerome Charyn’s Isaac Sidel novels, but more like those loosely knit narratives from the 1970s that wore their secular Jewishness lightly, such as Andrew Bergman’s Hollywood and Levine or Roger Simon’s The Big Fix. All of them highly readable and seemingly innocent regarding the harder edges of the genre, as if they’d only recently discovered the likes of Hammett or Chandler. Not really pastiche but using the genre’s tropes to explain this great big ball of confusion called the modern world. Without over-committing itself, The Last Songbird plays on those same tropes, but without the fake cynicism or wise-guy attitude, resulting in a narrative that takes the chaos of the city and the era as given.

Equally, one could claim that The Last Songbird belongs in still another sub-genre, that which investigates and revolves around the music industry. These run the gamut from Day Keene’s Payola, Arthur Lyons’ Three With a Bullet and Bill Moody’s Death of a Tenor Man to Elaine Jesmer’s Number One With a Bullet, Laurence Gonzales’s Jambeaux and, dare I say it, my own Cry For a Nickel, Die For a Dime. Do all these sub-genres thrown together simply indicate the lack of substance or commitment on the part of the author? Not necessarily. After all, unlike novels by the likes of Jim Thompson, David Goodis or Chester Himes, not every noir novel requires its author to put him or herself on the line, or to dig down so deep that it is difficult to understand how resurfacing can be possible. While Addy faces his own particular meltdown, there’s no reason to suspect that Weizmann might be undergoing a similar crisis; rather, one gets the impression that he is simply putting his considerable skills into constructing a good story while saying something that might resonate with the reader.

Noir-light it might be, but The Last Songbird has a lot going for it as it moves across Los Angeles, hitting various psycho-geographical points. And in going along for the ride, one moves from strip malls and strip joints to freeways and backstreets, from suburban McMansions to sleazy inner city apartments, from the Pacific Coast Highway to beach towns and criss-crossing freeways. At times it seems as though the novel’s various characters — “Every person a song in disguise” — are creatures of these various geographical points. There’s Addy’s semi-estranged suburban sister (actually his cousin), a relatively successful lawyer who is both jealous of Addy and looks down on him; the crazy dead mother, whom Addy recalls spending her final alcoholic years living with him out of her car; Annie’s ex-husband, a misogynistic creep who “In another life would have made dynamite extra in Fiddler On the Roof,” lives in Venice where he plots his takeover of the post-Annie pie; Addy’s friend, Ephraim, aka “Double Fry,” an orthodox Jewish photographer who lives on a boat at the beach, monitors police calls and dishes out words of Jewish wisdom; Bix, a fall-guy employed by Annie and allowed to live on her premises; Annie’s feminist ex-lover who lives near San Luis Obispo; and a machine shop owner, a black guy who, way back when, taught Annie to play guitar, and lives in “the last semi-industrial section of West Adams.” Add to that the assortment of young tearaways, women haters, sauna salesmen, memorabilia collectors, new age reprobates and, of course, pushy cops. Characters that seem to shape shift as the narrative progresses, none more so than Annie, both before and after her death.

In fact, The Last Songbird is the kind of novel that sneaks up on you. Before you know it, what began as an ordinary run-out written in a pedestrian style soon starts to show flashes of street-level lyricism and incisiveness. Perhaps it’s conscious on Weizmann’s part. Or maybe it just seems that way, as the novel quickly gathers steam until you feel you’re trapped in a narrative that might have been concocted by Raymond Chandler had the latter not had an elite private education and petit-bourgeois inclinations. But in the end, when it comes to a clear writing style along with the politics to back it up, Weizmann has more in common with Hammett, perhaps accompanied by the ingestion of some kind of Pynchon-pill of the Inherent Vice variety, whose effect makes things all the more dizzying and unpredictable, until L.A. turns into his own personal Poisonville:

“Bottrell returned with a cardboard file box and dropped into his lavender chair, which had shrunk into children’s furniture under his large frame. His reappearance gear-shifted the mood to even worse- I had been badly mistaken when I read him breezy. Now, he radiated the seething noblesse oblige of the Burdened Frontiersman. With Nguyen at least, you knew where you stood: Indochinese testosterone and shit to prove. There was geopolitical turbulence in her snicker as she took the box from Bottrell and drew some ancient forms from a folder — handwritten. My handwriting.”

But Weizmann has the sense to shy away from the mock Chandlerisms one has come to expect from so many neo-noir novels, opting instead for zingers that almost always hit their target, albeit in an off-centered way. Like morphing the overused Larkin family lines, which in Weizmann’s hands become “It takes a whole family to go insane.” Or playing off those same psycho-geographical cliches regarding what it’s like to live in a manufactured paradise: “Wherever you were, you were equidistant to the middle of nowhere. I tried to approximate the act of walking with an agonizing herky-jerky limp. The ape crawled up a staircase.” Okay, it’s true, Weizmann’s syntax can sometimes be a bit eccentric, defying grammar but rarely logic. At least to my ears, but then, no longer in L.A.’s linguistic loop, that could just be what passes for common usage in the southland these days. Because Weizmann never comes across as embittered or cynical, he can, suddenly shift attention away from the other to his hapless narrator:

But Weizmann has the sense to shy away from the mock Chandlerisms one has come to expect from so many neo-noir novels, opting instead for zingers that almost always hit their target, albeit in an off-centered way. Like morphing the overused Larkin family lines, which in Weizmann’s hands become “It takes a whole family to go insane.” Or playing off those same psycho-geographical cliches regarding what it’s like to live in a manufactured paradise: “Wherever you were, you were equidistant to the middle of nowhere. I tried to approximate the act of walking with an agonizing herky-jerky limp. The ape crawled up a staircase.” Okay, it’s true, Weizmann’s syntax can sometimes be a bit eccentric, defying grammar but rarely logic. At least to my ears, but then, no longer in L.A.’s linguistic loop, that could just be what passes for common usage in the southland these days. Because Weizmann never comes across as embittered or cynical, he can, suddenly shift attention away from the other to his hapless narrator:

“His organized yard, his bony shoulders and lazy hands and gold LCD watch, all gave the impression of a clam, clear mind, a sober tinkerer. But really he was buzzed on booze and propane and voltage — and he was hiding permanently in this metal pile-up. Hiding, just like the old man in Public Storage. How many of these hiders did any American city contain? I’m guessing tens of thousands. Including me.”

Having said all of that, I don’t really know how good — whatever “good” might mean — The Last Songbird actually is. All I can say is that it’s been one of the most entertaining crime novels I’ve read for some time. Full of surprises, Weizmann kept me guessing right to the end, unusual for such books these days. Nor am I sure how all the disparate parts of the novel come together. But somehow they do. This even though Weizmann takes the reader from one extreme to the other, but while doing so, never vacating the political terrain regarding gender politics, power relationships, family life, friendship, or celebrity culture. Weizmann, whose checkered past includes the anthology Drinking With Bukowski and the charming A History of Rock — A Grade-Schoolers Vision of Rock Music 1977-1980, as well as pages of new wave journalism, often filed under the name Shredder, for Flipside and The L.A. Weekly, accomplishes all of this with a light touch. More importantly, he fulfils one of the genre’s main requirements: that a fictional investigator, at the very least, investigate himself as much as the world around him. Although others have walked this way before, and some have ventured into more dangerous territory, Weizmann, with a nod towards Addy’s investigative future, can be congratulated on providing sufficient hard-boiled menace without tumbling full throttle into oblivion.

[Published by Melville House on May 23, 2023, 336 pages, $17.99 paperback]