What constitutes a “movement” in the arts? As time passes, how is authority conferred on the accomplishments of a movement? “The Pictures Generation, 1974-1984,” an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum running through August 2, seems designed for pondering these questions, even as Douglas Eklund, a Met photography curator who assembled the show, is determined to provide definitive answers reflecting on this group of artists.

“The historical achievement [of that generation] is secure,” he said in an Art in America interview, “but what that achievement actually is remains in question. The curator must make that first call.” In the accompanying book The Pictures Generation, Eklund makes his case at length via three essays, 240 colorplates and 93 figures.

“The historical achievement [of that generation] is secure,” he said in an Art in America interview, “but what that achievement actually is remains in question. The curator must make that first call.” In the accompanying book The Pictures Generation, Eklund makes his case at length via three essays, 240 colorplates and 93 figures.

His narrative locates the birth of the movement at a 1977 exhibition at the Artist Space called “Pictures” featuring work by Sherrie Levine, Jack Goldstein, Phillip Smith, Troy Brauntuch, and Robert Longo. The show was curated by Douglas Crimp whose essays sought to define a new role for photography. Thus early on, Crimp triggered the notion of an historical moment for those artists, most of whom emerged from the California Institute of the Arts or SUNY-Buffalo.

In “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism” (1980), a seminal essay for artists and writers, Crimp flipped Walter Benjamin’s indictment of “mechanical reproduction” on its head. “The desire of representation exists only insofar as it can never be fulfilled,” Crimp wrote, “insofar as the original always is deferred. It is only in the absence of the original that representation can take place.” To underscore the eternal absence of the original, the Pictures artists employed cultural imagery and made copies of copies. Reproduction, they claimed, is all there is to art. Every image is mediated by – and is made up of — previous images. Their art focused increasingly on printing processes rather than creating new images. In the mid-1960’s. Robert Rauschenberg transformed the picture’s surface into a “flatbed” accommodating a vast array of given images and artifacts. In the early 1970s, the younger artists accelerated and diversified this technique.

In “The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism” (1980), a seminal essay for artists and writers, Crimp flipped Walter Benjamin’s indictment of “mechanical reproduction” on its head. “The desire of representation exists only insofar as it can never be fulfilled,” Crimp wrote, “insofar as the original always is deferred. It is only in the absence of the original that representation can take place.” To underscore the eternal absence of the original, the Pictures artists employed cultural imagery and made copies of copies. Reproduction, they claimed, is all there is to art. Every image is mediated by – and is made up of — previous images. Their art focused increasingly on printing processes rather than creating new images. In the mid-1960’s. Robert Rauschenberg transformed the picture’s surface into a “flatbed” accommodating a vast array of given images and artifacts. In the early 1970s, the younger artists accelerated and diversified this technique.

Crimp took his lead from Roland Barthes who had spelled out an antagonism to linguistic messages that prevent “connoted meanings from proliferating” by maintaining the illusion that a signifier is the equivalent of the signified (which is always absent). This implied a critique of the wielder of such illusions. In the world of American poetry, Barthes’ key idea still inspires the odium expressed in some circles for the poetry of traditional lyric identities that allegedly represent and enforce an arrogant authority. It should be obvious, then, why The Pictures Generation is relevant to writers and artists in every medium. If this is Eklund’s historical documentary, it is also current events.

The way to deprive the power structure of its ability to rule through rhetoric and imagery was to deprive everyone of the ability to create anything authentic and original. So it was asserted that all selves are mediated identities, shaped by the sexual, racial, gender and national concepts and constructions, all reinforced by mass media. Absorbing the cultural critiques of thinkers like Jacques Lacan, Julia Kristeva, and Michel Foucault, the Pictures artists worked from Barthes’ notion (I quote Eklund here) that “any text (or image), rather than emitting a fixed meaning expressed by a single voice, was but a tissue of quotations that were themselves references to yet other texts … ‘The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author’ was a call to arms for the artists of the Pictures Generation.”

The way to deprive the power structure of its ability to rule through rhetoric and imagery was to deprive everyone of the ability to create anything authentic and original. So it was asserted that all selves are mediated identities, shaped by the sexual, racial, gender and national concepts and constructions, all reinforced by mass media. Absorbing the cultural critiques of thinkers like Jacques Lacan, Julia Kristeva, and Michel Foucault, the Pictures artists worked from Barthes’ notion (I quote Eklund here) that “any text (or image), rather than emitting a fixed meaning expressed by a single voice, was but a tissue of quotations that were themselves references to yet other texts … ‘The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author’ was a call to arms for the artists of the Pictures Generation.”

Another of Crimp’s bracing essays, “On the Museum’s Ruins” (1980), testified to “the fragility of the museum’s claims to represent anything coherent at all.” He writes, “The fiction of a creating subject gives way to a frank confiscation, quotation, excerptation, accumulation and repetition of already existing images.” But now, enshrined at the Met and discussed in The Pictures Generation,, some thirty “creating subjects” are being celebrated as quite distinct selves who zealously pursued experimental standards of indistinct expressivity. It turns out that the birth of the museum-goer does not entail the death of these artists, most of whom are still working and plugging the market value of their work. Eklund’s claims are, if anything, coherent.

Another of Crimp’s bracing essays, “On the Museum’s Ruins” (1980), testified to “the fragility of the museum’s claims to represent anything coherent at all.” He writes, “The fiction of a creating subject gives way to a frank confiscation, quotation, excerptation, accumulation and repetition of already existing images.” But now, enshrined at the Met and discussed in The Pictures Generation,, some thirty “creating subjects” are being celebrated as quite distinct selves who zealously pursued experimental standards of indistinct expressivity. It turns out that the birth of the museum-goer does not entail the death of these artists, most of whom are still working and plugging the market value of their work. Eklund’s claims are, if anything, coherent.

The Pictures people disclaimed the idea of the creator of originality. But as Eklund notes, originality was their constant goal. “By passing the premise of all previous art education — the progressive mastery of established techniques and skills – while also rejected the formal elaboration of the individual image in favor of deadpan arrangements of either deskilled or appropriated images, CalArts placed instead a premium on originality – expression that relies neither on the example of others nor on tropes and clichés.” Now their originality, intended to smash the idea of photography as museum art, has become a cliché for others to avoid.

The Pictures people disclaimed the idea of the creator of originality. But as Eklund notes, originality was their constant goal. “By passing the premise of all previous art education — the progressive mastery of established techniques and skills – while also rejected the formal elaboration of the individual image in favor of deadpan arrangements of either deskilled or appropriated images, CalArts placed instead a premium on originality – expression that relies neither on the example of others nor on tropes and clichés.” Now their originality, intended to smash the idea of photography as museum art, has become a cliché for others to avoid.

Eklund’s essays in The Pictures Generation take us through the emerging concepts, processes and output of a range of artists – too many to name. If the Met exhibit places too much emphasis on the artists’ reactions to American media culture, the essays offer a more diverse discussion of the forces at play in their practice.

Eklund’s essays in The Pictures Generation take us through the emerging concepts, processes and output of a range of artists – too many to name. If the Met exhibit places too much emphasis on the artists’ reactions to American media culture, the essays offer a more diverse discussion of the forces at play in their practice.

Eklund quotes Mike Kelley: “The general fear of being controlled by others … is part of the reason, I think, for the rise of the appropriation art movement. You become the thing that you fear or desire out of choice, rather than against your will.” But Eklund is shrewd enough to clarify that “a preemptive submission to the strategies and techniques of media manipulation makes appropriation both critical and collusive.” (Think of Frederick Seidel’s poetry in this regard — colluding with the culture he seems to satirize.) Reaching into the mainstream for its materials, the Pictures Generation thrived on this tension – working privately on art with a pretension to an absence of the private.

[Published by Yale University Press on May 26, 2009, 352 pages, $60.00 clothbound]

[Douglas Crimp’s essays are collected in On the Museum’s Ruins, MIT Press, a 1993 paperback still in print.]

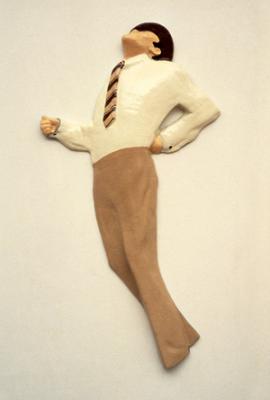

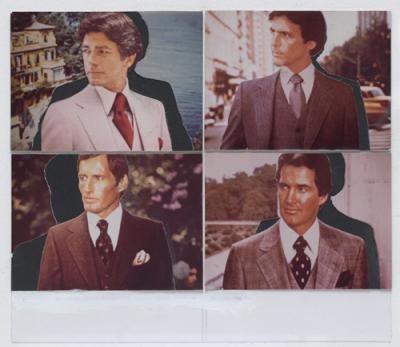

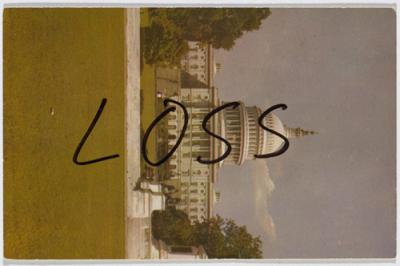

Images shown above:

1 — “The American Soldier,” Robert Longo, 1977, enamel on cast aluminum

2 — “Untitled (four single men with interchangeable backgrounds looking to the right),” Richard Prince, 1977, mixed media

3 — “Untitled (Nixon),” Paul McMahon, 1974, pastel on newspaper

4 — “Untitled Film Still #54,” Cindy Sherman, 1980

5 — from the series “Written-on Postcards,” Paul McMahon, 1975, ink on photomechanical reproductions