In his essay “The New Writing,” the Argentinean novelist César Aira extols prose fiction that puts “processes back on the throne which had been occupied until then by results.” For Aira, professionalization has “congealed” the novel and “shattered the form-content dialectic which makes art ‘artistic.’ ” He asks writers “to recuperate the amateur gesture, and to place it on a higher level of historical synthesis … to restore to art the ease with which it was once produced.”

But most readers go to the novel looking for a world, not for a process. It takes an inspired rogue talent to create pulsing life out of such knowing gestures, to restart the work of narrative from point zero, and to renounce the fixation on expected results in favor of a “procedure” attempting to construct, as Aira says, “the thing that is to be known … none other than the world. The world understood as a means of communication. It is not, then, a case of knowing but of acting.”

But most readers go to the novel looking for a world, not for a process. It takes an inspired rogue talent to create pulsing life out of such knowing gestures, to restart the work of narrative from point zero, and to renounce the fixation on expected results in favor of a “procedure” attempting to construct, as Aira says, “the thing that is to be known … none other than the world. The world understood as a means of communication. It is not, then, a case of knowing but of acting.”

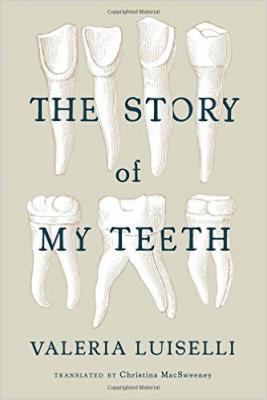

With her novel The Story of My Teeth, Valeria Luiselli (b. 1983) emerges not only as a playfully capable proceduralist but also as an entertaining and accomplished world-maker. The proceedings concern Gustavo Sánchez Sánchez, a.k.a. “Highway,” born 1945 in Mexico. At age 42, he became an auctioneer with the goal of earning enough cash to fix his bad teeth. He attributes his success as an auctioneer to his theory of “hyperbolics” – or, “in other words, as the great Quintilian had once said, by means of my hyperbolics, I could restore an object’s value through ‘an elegant surpassing of the truth.’ This meant that the stories I would tell about the lots would all be based on facts that were, occasionally, exaggerated, or, to put it another way, better illuminated.”

The narrative (“the beautiful tale of my dental autobiography”) is rife with many such mini-stories and odd allegories. As hyper-fiction or super-realism, The Story of My Teeth also tries to auction itself off as a version of reality, appealing to its audience through droll charm, inflating its slightness with a strange generosity of spirit. Its subject is its means: the enveloping and unspooling of stories (factual? fictional?). Did he replace his bad teeth with those of Marilyn Monroe? There is no “character development” — and there is no call for it. In its place are the many self-claims of Highway: “I’m a discreet sort of man” and “I have always been a well-grounded person” and “I’m a reasonable man despite a certain stubbornness.” The illusion of an entire life is presented – but the convention of “life-as-arc” doesn’t pertain. I was reminded throughout of the voices in Bohumil Hrabal’s novels, such as I Served the King of England, in which characters attempt to thrive in a shaken yet risible world.

The narrative (“the beautiful tale of my dental autobiography”) is rife with many such mini-stories and odd allegories. As hyper-fiction or super-realism, The Story of My Teeth also tries to auction itself off as a version of reality, appealing to its audience through droll charm, inflating its slightness with a strange generosity of spirit. Its subject is its means: the enveloping and unspooling of stories (factual? fictional?). Did he replace his bad teeth with those of Marilyn Monroe? There is no “character development” — and there is no call for it. In its place are the many self-claims of Highway: “I’m a discreet sort of man” and “I have always been a well-grounded person” and “I’m a reasonable man despite a certain stubbornness.” The illusion of an entire life is presented – but the convention of “life-as-arc” doesn’t pertain. I was reminded throughout of the voices in Bohumil Hrabal’s novels, such as I Served the King of England, in which characters attempt to thrive in a shaken yet risible world.

The Story of My Teeth begins in the voice of Highway who, now an elderly gent, describes his rise as an auctioneer and a notorious person in the crowded city of Ecatepec where he grew up and owns some property including his mansion and warehouse of collectibles in Calle Disneylandia. At mid-book, he meets Jacobo de Voragine, a would-be writer and tour guide whom he recruits to write his autobiography. Has Voragine been ghostwriting this story since page one? They work together on some illicit auctioning business.

Then, Voragine takes over in his own voice. Certain past events are further explained. New stories overtake old ones. Voragine says, “When Highway first began to recount his stories to me, I thought he was a compulsive liar. But then, living with him, I realized that it had less to do with lying than surpassing the truth. Highway was one of those vast, eternal spirits. His presence was at times menacing – not because he was a real threat to anyone, but because, in comparison with his ferocious freedom, all the parameters we normally use to measure our actions seem trivial.”

Aira states that the work of proceduralists “will always seem a little irresponsible or barbarous,” incorporating and inviting ridicule. The Story of My Teeth qualifies in that sense. But what is Luiselli’s process? She spells it out in the final chapter: “I decided to write a novel in installments for the workers” of the Jumex juice factory in Ecatepec; the company holds the Jumex Collection, “one of the most important contemporary art collections in the world.” She notes “the strange métier of ‘tobacco readers’” in Cuban cigar factories, people who would read aloud to workers to reduce tedium and stress – and in this way, her drafts were read aloud to the workers whose reactions and discussion were recorded and sent back to Luiselli. “I’d then write the next installment, and send it back to them, and so on.” In addition to the narrative, there are supplementary photographs of Ecatepec with citations, Chinese aphorisms, and quotations from philosophers about language and thought. She believes she has created a “collective ‘novel-essay’ about the production of value and meaning in contemporary art and literature.”

Aira states that the work of proceduralists “will always seem a little irresponsible or barbarous,” incorporating and inviting ridicule. The Story of My Teeth qualifies in that sense. But what is Luiselli’s process? She spells it out in the final chapter: “I decided to write a novel in installments for the workers” of the Jumex juice factory in Ecatepec; the company holds the Jumex Collection, “one of the most important contemporary art collections in the world.” She notes “the strange métier of ‘tobacco readers’” in Cuban cigar factories, people who would read aloud to workers to reduce tedium and stress – and in this way, her drafts were read aloud to the workers whose reactions and discussion were recorded and sent back to Luiselli. “I’d then write the next installment, and send it back to them, and so on.” In addition to the narrative, there are supplementary photographs of Ecatepec with citations, Chinese aphorisms, and quotations from philosophers about language and thought. She believes she has created a “collective ‘novel-essay’ about the production of value and meaning in contemporary art and literature.”

Well, fine. Luiselli is in touch with the “site of reception” of her work, as the artist-ethicists like to say. But the text functions well without this glossing – the story adequately implies its values. Voragine gets at “the production of value” while describing Highway’s “allegoric method, where it is not objects that are sold, but the stories that give them value and meaning. The allegorics were, according to Highway, ‘postcapitalist, radical recycling auctions that would save the world from its existential condition as the garbage can of history.’”

The Story of My Teeth is a discursive, jesting novel that will reward your reading by lighting up the part of the brain where thoughtfulness enjoys itself without requiring the net profit of knowledge.

[Published by Coffee House Press on September 15, 2015. 184 pages, $16.95 paperback]