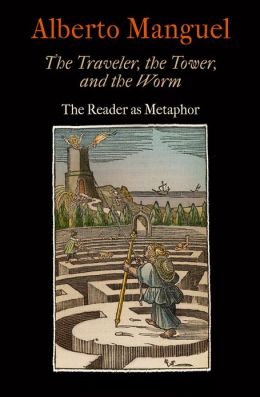

In his forty-fourth book as writer or editor, Alberto Manguel once again makes spirited claims for the interaction between reader and book – the “book fool” and the world-as-words. Here, the world is like a book open to interpretation and one’s life is like a voyage through that book. Reading is a kind of enlightened folly. “Language barely glances the surface of our experience,” he writes, “and transmits from one person to another, in a supposedly shared conventional code, imperfect and ambiguous notations that rely both on the careful intelligence of the one who speaks or writes and on the creative intelligence of the one who listens or reads.”

In this sense, metaphors are what “language resorts to … [and] are, ultimately, a confession of language’s failure to communicate directly.” Nevertheless, our world “is a book we are meant to read. Its signs “have a meaning, even if that meaning lies beyond our grasp.”

In this sense, metaphors are what “language resorts to … [and] are, ultimately, a confession of language’s failure to communicate directly.” Nevertheless, our world “is a book we are meant to read. Its signs “have a meaning, even if that meaning lies beyond our grasp.”

These insights are not intended to convince non-readers to obtain library cards, since Manguel’s sentences must be read in the first place. No, Manguel is a docent speaking quietly among our own bookshelves, a one-sided conversation between believers who mutually sense the strangeness of these pleasures.

In The Traveler, the Tower, and the Worm, Manguel begins with a sweeping tour through Mesopotamia and Gilgamesh, ancient Judaism and Saint John’s Gospel, Saint Augustine and Virgil, on to Plotinus’ third century, Dante, and finally to moderns like Cees Nooteboom and Orhan Pamuk – all establishing that “reading allows us to experience our intuitions as facts, and to transform the moving through experience into a recognizable passage through the text.”

Nooteboom remarks in one of his splendid books on travel that “anyone who is constantly travelling is always somewhere else, and therefore always absent.” To read is to be elsewhere. If travelling is transience, then reading-as-journey grates against the certainties of assertion and denials of flux.

Nooteboom remarks in one of his splendid books on travel that “anyone who is constantly travelling is always somewhere else, and therefore always absent.” To read is to be elsewhere. If travelling is transience, then reading-as-journey grates against the certainties of assertion and denials of flux.

In part two, he considers “reading as alienation from the world” – the sense of removal that may entail “an undercurrent of guilt, a self-censuring of the very act of quiet thinking.” In this tower, a cloister of inaction, we pursue an aesthetic fact, a thing Borges once described as “the imminence of a revelation that does not take place.” In part three, Manguel considers The Bookworm, the burrower of words, affectionately chided for mistaking “accumulation of books for the acquisition of knowledge.”

Charmingly, Manguel tilts his head at the bookworm and intuits something else, a related “double bind” experienced by a reader, “the wish that what is told on the page be true, and the belief that it is not.” The reader reacts by applying a certain pressure on this sensation, becoming one’s own “mediator between the perception of fiction and the perception of reality.”

Charmingly, Manguel tilts his head at the bookworm and intuits something else, a related “double bind” experienced by a reader, “the wish that what is told on the page be true, and the belief that it is not.” The reader reacts by applying a certain pressure on this sensation, becoming one’s own “mediator between the perception of fiction and the perception of reality.”

In 2009, President Nicolas Sarkozy learned that French civil servants were expected to have studied a classic seventeenth century novel for their qualifying exams. “Why read the Princesse de Clèves?” he asked. The philosopher and writer Hélène Cixous, disgusted by what she heard as philistinism, responded, “Why this fury against French language and literature? This resentment, this frenzy? Because here is a world on which he cannot pull the old trick of the law of the strongest. He doesn’t know how to seduce thought, how to reduce it, dominate it, make it crawl.”

Manguel agrees with Cixous – but he rarely seems to regard the reader as under attack (unless by digital books). “The verse, sentence, or story will always interest us more than the material thing itself, “ he says, “because we are creatures of feeble perceptions, like moles in the sun, betrayed by our senses, and even though literary language is an uncertain, unreliable instrument, it is, however, capable, in a few miraculous moments, of helping us see the world.”

Perhaps too relaxed for some of us, Manguel still would not deny the more aggressive postures of some writers. Writing about Mandelstam, Seamus Heaney said, “Poetry may indeed be a lost cause, but each poet must raise his voice like a pretender’s flag.” That much sounds like Manguel. But Heaney continues, “Whether the world falls into the hands of the security forces or the fat-necked speculators, he must get in under his phalanx of words and start resisting.”

[Published by the University of Pennsylvania Press on August 1, 2013. 144 pages, $$24.95 hardcover]

On The Seduction Of Thought

Yes, that Alberto Manguel, he’s a canny fellow. I love him too. But let’s go one better than the lost cause of poetry. Let’s put some bounce in the walk. And more leaps. And growls. We might look like fools.

more Manguel

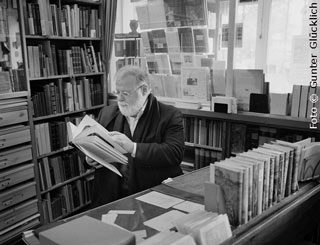

I’ll recommend two other Manguel titles for those who want to discover this wonderfully humane and articulate writer. First, A Reader on Reading from Yale (2010), and then The Library at Night (2006). He has also written a fine book on Borges but I can’t recall the title just now.

Manguel and Borges

When Manguel was just a teenager, he met Borges at a bookstore in Buenos Aires where he worked after school. Borges was almost blind and Manguel became one of his readers. Manguel’s book on his mentor is titled With Borges and was published in 2006 by Telegram Books. Incidentally, Manguel has written most of his own books in English.