Sam Savage has a flair for failure. Born in 1940 in South Carolina, he wrote poetry and prose fiction throughout his life without publishing much. He had a fling with academia, earning a degree at Yale and studying philosophy in Heidelberg. There was a period of political activism. But he returned to and lived for many years in South Carolina where he and his wife worked “at terrible jobs that kept us out of trailers, just barely,” as he told The Telegraph.

He was interviewed by the English newspaper because in 2008 his second novel, Firmin: Adventures of a Metropolitan Lowlife, was a smash hit in Europe. The story is narrated by Firmin, a literary rat born in the cellar of a Boston bookstore on a nest of gnawed pages of Finnegan’s Wake, or as Firmin puts it, “on the defoliated pages of the world’s most unread masterpiece.” A voracious reader, Firmin is a self-pitying lover of popular human culture and a failure at writing. Like Firmin’s nursery, Savage’s writing impulse begins in (and ultimately renovates) the high Modernist tradition.

He was interviewed by the English newspaper because in 2008 his second novel, Firmin: Adventures of a Metropolitan Lowlife, was a smash hit in Europe. The story is narrated by Firmin, a literary rat born in the cellar of a Boston bookstore on a nest of gnawed pages of Finnegan’s Wake, or as Firmin puts it, “on the defoliated pages of the world’s most unread masterpiece.” A voracious reader, Firmin is a self-pitying lover of popular human culture and a failure at writing. Like Firmin’s nursery, Savage’s writing impulse begins in (and ultimately renovates) the high Modernist tradition.

After selling his late father’s southern timberland to investors, Savage and wife Nora moved to Madison, Wisconsin where his first novel, The Criminal Life of Effie O., was unexpectedly birthed. He said, “I had always wanted to be a writer. I’d written a lot of poetry, which I didn’t like then and don’t like now. I found it very unsatisfactory. When we moved up here, we had to clear everything out, all our books and papers and everything. And I found fragments of novels, whole chapters that I’d written over the past 35 or 40 years … Not only did I not remember writing them, I couldn’t recognize the person who did write them. I suppose that in one sense the person who wrote Firmin didn’t come into existence until later, and I couldn’t have written it at any other time.

“But also, Firmin’s essential experience is of failure – failure to write, failure to complete – and I’d had that experience. You can’t have that at 30, because you think it’s going to happen. You have to reach a certain age before you realize that it isn’t.”

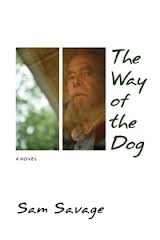

There’s an autumnal draft of mordant assessment drifting through the two novels that followed, The Cry of the Sloth (2009) and Glass (2011). Now, Savage has produced The Way of the Dog to continue this remarkable string of cousinly works. Its narrator is Harold Nivenson, failed artist, one-time art collector, and geriatric crank. The content comprises his brief notes, apparently culled from “ten of thousands” of index cards stashed around his house – observations, outbursts, memories, complaints, accusations, anecdotes. He is making a final stand bristling with resentment and rue:

There’s an autumnal draft of mordant assessment drifting through the two novels that followed, The Cry of the Sloth (2009) and Glass (2011). Now, Savage has produced The Way of the Dog to continue this remarkable string of cousinly works. Its narrator is Harold Nivenson, failed artist, one-time art collector, and geriatric crank. The content comprises his brief notes, apparently culled from “ten of thousands” of index cards stashed around his house – observations, outbursts, memories, complaints, accusations, anecdotes. He is making a final stand bristling with resentment and rue:

“In the great prenatal sorting of souls I stumbled into the wrong species, I have been thinking. I was destined for something smaller, meaner, more solitary – a vile little insect, perhaps, like the character in Kafka’s great story, who wakes up one morning and discovers he has been transformed into a big cockroach. Of course, ‘deep down’ he was that all along, and one day he wakes up and knows it.

I have learned it gradually. A long descent into vileness.

Scaling desiccated skin of snake, bloated belly of toad, fleshless legs of bird, smell of goat, face of camel, mind of berserk elk pulled down by wolves. A hobbler, a foot-dragger, stumbling on cracks in the sidewalk.

I have a gun.”

Chekhov’s dictum immediately comes to mind: a pistol introduced in Act I must fire in the last act. But will the trigger be pulled in Nivenson’s case? He says he is capable of shooting his neighbor, Professor Enid Diamond, who ignores him when she passes on the street. She has written “eleven long novels, eleven multigenerational sagas, … The newspaper calls her a literary powerhouse. She is a literary industrial-scale waste producer. Obviously she is using some kind of trick, you can’t write that many novels unless you have a trick. For example, the same novel is being written over and over. That is what most of them do.” He blames her for disturbing “the equanimous mental state in which I might have worked with complete indifference.”

But the professor is a minor antagonist compared to Meininger, the commercially successful painter who lodged in the house for several years, attracting acolytes like flies. The house itself is Nivenson’s nemesis. After years of scholarly travels and producing some slender writings on Balthus, Nivenson came into some money and acquired the house. Now thirty years have passed and the ill-kept house is hung with art and remnants of his years living alone there with his dog, Roy, now dead. Moll, Nivenson’s estranged wife, returns to nurse him.

The Way of the Dog is Nivenson’s bitter life inventory, wracked with self-disgust and vitriol. Although Savage maintains a steadily caustic tone, the startling clarity and unrestrained candor of Nivenson’s remarks yield a deeply registering performance. His targets include art and artists, academia, gentrification, filial and marital relationships, happiness, and popular culture.

But his extremes implicitly point to their opposites – just as the mockery of Diamond’s conventional novels (a gratifying critique if Savage’s writing resonates with you) loses some force when one considers that Savage has also found a mode that rolls along “over and over” through his five novels. If Nivenson was destined to be “something smaller, meaner, more solitary,” that’s because he sports the same DNA as Firmin the Rat.

Nivenson’s meditations are circuitous, returning to heap abuse on the allegedly destructive acts of Meininger and the insufferable habits of his neighbors. He vacillates as well between dishing out and taking blame. It is a blameworthy world. Other people are the problem:

“Though they themselves don’t think, are incapable of thinking, they sense the danger of someone who makes a habit of thinking matters all the way through to the end, to their logical rather than their emotional conclusion, who does not stop thinking at then point where he happens to feel comfortable, I have always believed. The thoughts, unchecked, either go round and round like a snake biting its tail or they shoot straight ahead like bullets, and one ends up a madman or an assassin, I think now.”

The pleasure of listening to Nivenson comes from his willingness to struggle for that small measure of achievement when his words are like bullets. The reader who won’t abide this novel is one who demands an “emotional conclusion.” The spectre of “genuine art” versus the ersatz appears throughout the novel – and disparagement for the facile comfort taken by the “average person” in conventional artistic expression. It is impossible not to make the connection between Nivenson and Savage since The Way of the Dog isn’t the sort of book Professor Diamond would write. But Savage hasn’t written a screed, and Nivenson’s failure is a true failure – so true and textured that one must hear him through to the end.

The pleasure of listening to Nivenson comes from his willingness to struggle for that small measure of achievement when his words are like bullets. The reader who won’t abide this novel is one who demands an “emotional conclusion.” The spectre of “genuine art” versus the ersatz appears throughout the novel – and disparagement for the facile comfort taken by the “average person” in conventional artistic expression. It is impossible not to make the connection between Nivenson and Savage since The Way of the Dog isn’t the sort of book Professor Diamond would write. But Savage hasn’t written a screed, and Nivenson’s failure is a true failure – so true and textured that one must hear him through to the end.

“True stories are never the best stories,” he says, “because they lack a proper ending and a proper meaning, but they are the ones that are most faithful to life.” Here Nivenson and Savage both make the critical point about their efforts. “A story is like a path through a wood. It is marked by a series of signs, like directional arrows that say, ‘Go this way.’ A story compels us to go that way.” The Way of the Dog may not be Savage’s most charming book, but it is his most compelling.

[Published by Coffee House Press on January 8, 2013. 153 pages, $14.95 paperback original]