Hijacked by a book of poems, I want to know more about my captor. What has given rise to such intentions? Mark Strand said that a poem’s unstated command is “Be like me.” If this is the case, then my inquiry about the poems’ sources is not extra-literary. I am not abusing the poems by sniffing around their edges for the residue of origins – because I have surrendered and become like the poem, I am probing my own indistinct provenance, and I pose a congenial threat to myself.

Poems say “be like me” because (contrary to critical complaints) they never actually abandon the art’s long inclination to instruct and reflect in favor of description and admission. Sandra Lim proves that the schism is bogus in her remarkable second collection, The Wilderness. Blurring the lines between and pivoting around all these actions, the poems nominate themselves as models of strangely spoken behavior. They simultaneously ask and show how to live, which here is coincident with figuring out how to make art.

Poems say “be like me” because (contrary to critical complaints) they never actually abandon the art’s long inclination to instruct and reflect in favor of description and admission. Sandra Lim proves that the schism is bogus in her remarkable second collection, The Wilderness. Blurring the lines between and pivoting around all these actions, the poems nominate themselves as models of strangely spoken behavior. They simultaneously ask and show how to live, which here is coincident with figuring out how to make art.

The opening poem, “Small Container, Fury,” begins with allusions to Rembrandt and Nabokov, then leaps to a quaint trope of nature, concluding:

How exciting spring is! And how errant,

holding out love and death

like a platter of the daintiest cakes.

As I do my work, I think, let me topple,

wear thin. Let the world eat me, but

then, let the world sob, not me.

These are first wishes that mimic final ones. The lines also comprise a clarification and a warning. She asserts that her work will not trade strictly in renunciations – a caution to the reader who may expect such a blunt gaze and bluff voice to revel in the bitter enjoyment of what has not been granted and is under suspicion. “Fury” here is a cool ferocity, not willful pique. The offering up of oneself to toppling and fraying is not a scourging but an anointing. Lim is more invested in what remains (however stark) than in what has been lost. But she also mocks. Spring may be exciting but it yields such ridiculous tropes. The exclamation point after “exciting” indicates that she is trying — but perhaps is ill-equipped -– to exercise pitch as well as tone.

Querying the nature of the world, Lim establishes a tone at once vulnerable and aggressive, churning with uncertainties but inclined to valorize them with utmost care and caution. A fearlessness of statement is abetted by nimble pivots between the hieratic and the demotic. She knows when to back off, when to thrust, but in either mode she pronounces. The vulnerability is expressed through assertions that may sound elementary or even naïve as if something basic has just been encountered. In “Snowdrops” she writes, “Even a propped skull is human nature. And its humor is monstrous, rich with an existence that owes nothing to anyone.” But there is a more serious if obscured motive at work here, the marking off of one’s isolate space, rich with existence, where nothing is owed to given terms of personhood. These are not poems about intimacies and relationships.

Querying the nature of the world, Lim establishes a tone at once vulnerable and aggressive, churning with uncertainties but inclined to valorize them with utmost care and caution. A fearlessness of statement is abetted by nimble pivots between the hieratic and the demotic. She knows when to back off, when to thrust, but in either mode she pronounces. The vulnerability is expressed through assertions that may sound elementary or even naïve as if something basic has just been encountered. In “Snowdrops” she writes, “Even a propped skull is human nature. And its humor is monstrous, rich with an existence that owes nothing to anyone.” But there is a more serious if obscured motive at work here, the marking off of one’s isolate space, rich with existence, where nothing is owed to given terms of personhood. These are not poems about intimacies and relationships.

Some of the poems, like “The New World” (below), are sentence-based, encouraging chasm-vaults between statements. They not only emit the sounds of a restive, interrogating mind, but give the reader a conveyance that stops at all the key vantage points of this curious location:

THE NEW WORLD

The world we see never is the world that is: the senseless morning light cuts its white eyes open.

What is the lecture of the darkest pines, the way they hang their stillness against us?

If I beggar myself for love, do I move from night into more night?

If I swallow a mouthful of ground glass, do I not slip past languages?

Thunderous wakefulness is ceaseless needles through the casing.

There are only the living and the dead: roses climbing a battered trellis. A caterpillar turns its hard black goggles upon the cold meat of me.

Drinking wholly from the world remains dark argument, hardly moral.

To be living in the feast sweetens my idea of death, its foreknowledge and its art.

Affliction, make yourself a scar upon my house and count the ways.

As ever, the world is too much with us, or not quite enough. But Lim’s affect is not weariness; she is not a maker of lamentations. A new world must be made out of this wilderness. Her interest is not in conifers or caterpillars. In her poems, one listens to someone suggesting extremely broad associations in which individual objects are not elevated into separate marvels. Everything has the same fate. There is only one agenda: to erode or leap over the hurdles that prevent a vital penetration. “Ceaseless needles through the casing.” One hears new terms that “slip past languages.” Strangely, “the world we see” is the impermanent one and to “drink wholly” from it is “hardly moral.” The envisioned world and the moment one speaks of it (one and the same) comprise the enduring appearances. In “Wildlife” she writes, “Black flies from the creek fall into my teacup — / keep one eye on the world, they say.”

Through eloquence, Lim renews classic gestures. In The Wilderness, eloquence is a compulsion, not a costume. Its sound is original. “Eloquence does not represent the real, it replaces it with its own voice, complacently narcissistic,” writes Denis Donoghue in On Eloquence. “It is the charisma of speech, claiming to transcend the properties of law, custom, and reference: an inspired grace, a favor, like the gift of tongues … If eloquence is a factor added to life, what it mainly says is that nothing necessarily coincides with itself: in passing from existence to expression, there is always the possibility of enhancement.” This possibility is the governance of renunciation.

Through eloquence, Lim renews classic gestures. In The Wilderness, eloquence is a compulsion, not a costume. Its sound is original. “Eloquence does not represent the real, it replaces it with its own voice, complacently narcissistic,” writes Denis Donoghue in On Eloquence. “It is the charisma of speech, claiming to transcend the properties of law, custom, and reference: an inspired grace, a favor, like the gift of tongues … If eloquence is a factor added to life, what it mainly says is that nothing necessarily coincides with itself: in passing from existence to expression, there is always the possibility of enhancement.” This possibility is the governance of renunciation.

Returning to Lim’s first book, Loveliest Grotesque (Kore Press, 2006), one may find the emerging attributes of Lim’s work: “You, both scorched and shining in the terror / of the equivocal moment …” It is a book animated by the discovery of one’s power and the freedom to “be large with those small fears.” It brims with the excess of its gurlesque self, a celebration of free access to a wild interior. And yet The Wilderness, so much more pared down and paced, seems to take greater freedoms and risks. In those eight intervening years, Lim appears to have made more deliberate demands on herself. Take these two books in hand and speculate about the evolution of a singular poet.

Part II of The Wilderness includes the long quasi-epigrammatic poem “Ver Novum” with sections like this:

If word can become flesh,

now leaning its forehead against cool glass,

now discovering a passion

for Thomas Hardy,

can’t it be the spur that coaxes

out the strangest beast

within the beast, the spirit?

Lim circles around her obsessions like a beast of prey, and The Wilderness as a whole dares to return its gaze again and again to its most prickly puzzlements. The atmosphere is rife with oppositions: the effort of coming to final terms locks horns with the stubborn limits of understanding, and the world is sated with both mystery and monotony. There is a certain pride taken in charting the path toward wakefulness, but also consternation about the cost of lingering in such a middle state. The first line of “Amor Fati” (below) is hardly novel – Paul Éluard spelled it out a hundred years ago. But the second line stains it with second-guessing:

AMOR FATI

Inside every world there is another world trying to get out,

and there is something in you that would like to discount this world.

The stars could rise in darkness over heartbreaking coasts,

and you would not know if you were ruining your life or beginning a real one.

You could claim professional fondness for the world around you;

the pictures would dissolve under the paint coming alive,

and you would only feel a phantom skip of the heart, absorbed so in the colors.

Your disbelief is a later novel emerging in the long, long shadow of an earlier one—

is this the great world, which is whatever is the case?

The sustained helplessness you feel in the long emptiness of days is matched

by the new suspiciousness and wrath you wake to each morning.

Isn’t this a relationship with your death, too, to fall in love with your inscrutable life?

Your teeth fill with cavities. There is always unearned happiness for some,

and the criminal feeling of solitude. Always, everyone lies about his life.

Now you will tell me that I am mistaken about the tamping down of renunciation. But I insist. “Amor Fati” signifies the taking of inventory. The unblinking accounting is what matters. Somehow it is always good news when Lim speaks most mordantly. A “professional fondness for the world” would seem to entail a love of its palette more than an appreciation of its impenetrable, elusive shapes. The Wilderness vacillates between an adoration of its self-propelled world and an unsparing assessment of its condition, but the two gestures combine to form a mind that keeps one eye on its own integrity. In “Vous Et Nul Autre,” she points an accusing finger at “Feelings escaping out from the / willful I, the one that wants always // to place its unthinkable petals on high branches.”

This speaker contests everything in herself (thus, in myself, the implicated captive). The testing is an affirmation. The “you” in “Amor Fati” is herself, saved from her own mendacity by language.

The Wilderness is arranged in four sections to maximize variations within a circumscribed environment. Two fine poems, “Certainty” and “Homage to Mistress Bradstreet,” take up the wilderness in the foundational worlds of Edward Taylor and Anne Bradstreet. Of Taylor’s world she says, “Consider the strange and riotous interior, through which so many nameless things fly.” And of the latter: “How could this territory have anything to do with us? // There is something exciting about it, nevertheless. / Something mistaken and wholly familiar, / hatchet-minded, and eager with beginning.”

The Wilderness is arranged in four sections to maximize variations within a circumscribed environment. Two fine poems, “Certainty” and “Homage to Mistress Bradstreet,” take up the wilderness in the foundational worlds of Edward Taylor and Anne Bradstreet. Of Taylor’s world she says, “Consider the strange and riotous interior, through which so many nameless things fly.” And of the latter: “How could this territory have anything to do with us? // There is something exciting about it, nevertheless. / Something mistaken and wholly familiar, / hatchet-minded, and eager with beginning.”

The incalculable sum of The Wilderness enshadows any and all of its individual assertions, alerts, and advisements. But there are moments, as in the concluding lines below from “Aubade,” when the whole is glimpsed and with a sudden jolt one realizes how much Sandra Lim has accomplished in this splendid book:

I would sit down to eat as if I were reading a poem.

I would observe how the night

went into the day with a special grandeur.

It would be like swallowing a sword and growing surprised

by how good it is, how it opens.

And then maybe to sing out with a throat like that –

saying look,

look how the world has touched me.

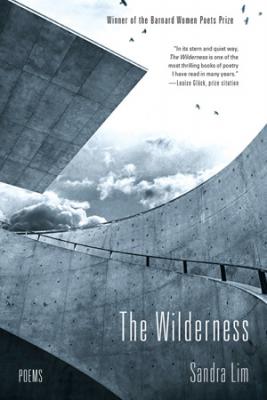

[Published by W.W.Norton on September 22, 2014. 96 pages, $$15.95 paperback. Winner of the 2013 Barnard Women Poets Prize awarded by Louise Glück.]