Abysses / translated by Chris Turner (Seagull Books/ Univ. of Chicago)

The Hatred of Music / translated by Matthew Amos & Fredrik Rönnbäck (Yale University Press)

A Terrace in Rome / translated by Douglas Penick & Charles Ré (Wakefield Press)

* * * * * * * *

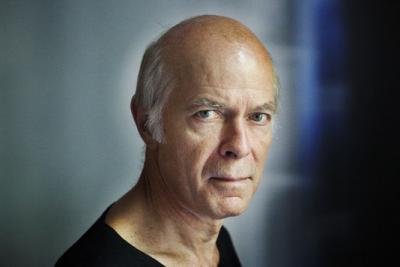

By the time Pascal Quignard (b. 1948) was awarded the Prix Goncourt for Les ombres errantes (The Roving Shadows) in 2002, he had already produced 19 other titles. These included Tous les matins du monde (All the Mornings in the World), his 1991 novel that was made into an acclaimed film (he co-wrote the screenplay with director Alain Corneau). His bibliography now includes more than 40 titles (plus a dozen briefer publications) spanning and often blending several genres – prose fiction, prose poetry, history, biography, philosophy, criticism, folklore and mythology, notebook and fragments.

It is diverting to imagine the circumstances under which a book like The Roving Shadows would earn the most prestigious literary prize in the United States as it did in France as the first non-novel to earn the Goncourt in six decades. Each of its 55 chapters leaps about between narrative fragments, citations, aphorisms, discursive references, and anecdotes. While taking broad liberties with genre, The Roving Shadows, like all of Quignard’s work, is also sonically penetrating. A severe, restless wisdom is voiced through terse syntax and sudden emphases – but the one who speaks is always enshadowed within the literature and mythology he evokes.

It is diverting to imagine the circumstances under which a book like The Roving Shadows would earn the most prestigious literary prize in the United States as it did in France as the first non-novel to earn the Goncourt in six decades. Each of its 55 chapters leaps about between narrative fragments, citations, aphorisms, discursive references, and anecdotes. While taking broad liberties with genre, The Roving Shadows, like all of Quignard’s work, is also sonically penetrating. A severe, restless wisdom is voiced through terse syntax and sudden emphases – but the one who speaks is always enshadowed within the literature and mythology he evokes.

His rhythmic prose serves his impulse to teach through a plangent lyricism that accommodates assertion and deeply felt experience:

Without solitude, without the test of time, without the passion for silence, without the excitation and retention of the whole body, without a frightened stumbling, without wandering into a region of shade and invisibility, without memory of animality, without melancholy, without isolation in melancholy, there is no joy.

The Roving Shadows is the first volume in a sequence called Le Dernier Royaume (The Last Kingdom) and Abysses is the third to be translated by Chris Turner. (Five Last Kingdom volumes have been published in France.) Common to the series is Quignard’s obsession with The Erstwhile, by which he indicates not only all that has conceived and preceded us but also the lost capability to apprehend the timeless. The Erstwhile exists in our Present and seems to call to us yet it is lost to us. Naturally, desire is another of Quignard’s subjects. “Who does not love what he has lost?” he writes in The Roving Shadows. “We must love the lost, and love even the Erstwhile in that which is lost.”

Abysses is preoccupied with time, especially “the two-phase beat comprising the lost and the imminent.” One catches flashes of the Erstwhile in the frantic search for the Present. A terror is triggered by “the dispersive, unstable explosiveness of time.” Part of Quignard’s mission is simply to point out that “what has not entered the heart of man invades us like an abyss.” His critiques are withering:

Abysses is preoccupied with time, especially “the two-phase beat comprising the lost and the imminent.” One catches flashes of the Erstwhile in the frantic search for the Present. A terror is triggered by “the dispersive, unstable explosiveness of time.” Part of Quignard’s mission is simply to point out that “what has not entered the heart of man invades us like an abyss.” His critiques are withering:

Human societies, derived imperceptibly from animal societies, are doomed to a cycle of predation and wintering – of war and respite from war – which is increasingly out of attunement with the linguistic, technical, mathematical, industrial, financial, linear temporality that humanity believes reflects its nature but that produces a rhythm by which it does not live.

And yet, just as he tolls the bell of our disinheritance, he parts the curtains for the possibility of redemption through language – those countervailing rhythms which awaken us. “Writing brings into being a gap,” he writes, “a discrepancy. It disjoints dialogue which was previously indistinct and continuous. The letter is the staying, the deferring, the sabbatical, the – transitory or fallacious or mendacious or fantastical or fictitious – other world. Writing institutes the contre-temps — the delay.” Through poetry and story and the mind’s wandering, one catches a whiff of the Erstwhile. The rhythms, imagery, and freed vectors of Quignard’s writing comprise both a conveyance and a model. Disjointed distinctness – this is his quality.

In describing his project, I haven’t even begun to mention the content in Abysses — the many stories and bits of lore selected for subtle resonance with Quignard’s bold themes. Some of the 91 short chapters’ titles include: Shakespeare, Nostalgia, The Antiquated, The Disconnected Telephone, On the Happy Ending, On Force, Mercury, Dreams, The Snail, Treatise on the Sky, On Busoni, On Dead Time, Chuang-Tzu’s Bird, Modernity, Reading, Antique Hunting, The Abyss of 1945, Story of the Woman Called the Gray One, Rome, Virgil, Red.

In describing his project, I haven’t even begun to mention the content in Abysses — the many stories and bits of lore selected for subtle resonance with Quignard’s bold themes. Some of the 91 short chapters’ titles include: Shakespeare, Nostalgia, The Antiquated, The Disconnected Telephone, On the Happy Ending, On Force, Mercury, Dreams, The Snail, Treatise on the Sky, On Busoni, On Dead Time, Chuang-Tzu’s Bird, Modernity, Reading, Antique Hunting, The Abyss of 1945, Story of the Woman Called the Gray One, Rome, Virgil, Red.

Descended from a line of organists, Quignard is also an accomplished cellist who helped establish the International Festival of Baroque Opera and Theatre at Versailles. He wrote La leçon de musique (The Music Lesson) (1987) which asks if music postpones time, plays with time, or cancels it altogether. Yet in 1994, Quignard divorced himself from the festival and playing music, and published La haine de la musique (The Hatred of Music). In fact, he resigned from all professional activities including his position at Gallimard. Quignard’s mistrust of modern culture runs deep. He has warned, ‘Those who try to collude with the system will become its images” (in The Roving Shadows) and “Humanity can no longer entrust anything of itself to anything” (Abysses). Yet he did anything but renounce the language arts. Not so with music:

Suddenly infinitely amplified by the invention of electricity and the multiplication of its technology, [music] has become incessant, aggressing night and day, in the commercial streets of city centers, in shopping centers, in arcades, in department stores, in bookstores, in lobbies of foreign banks, even at the beach, in private apartments, in restaurants, in taxis, in the metro, in airports. Even in airplanes during takeoff and landing.

The Hatred of Music builds up to its indictment, finally considering the music that had been played at Nazi concentration camps. But the book begins with the aspects of music that align it with that feel for the Erstwhile. Apparently Quignard believes that music is more susceptible than literature to kidnapping by the gods of profit – but also more capable than literature of restraining us within the chains of getting and spending. Ultimately, The Hatred of Music is an appeal for the contemplation of silence. Despite its pique, the text teems with insights into our attention to sound.

In Abysses, Quignard writes, “All is not said.” That is, all cannot be said. And from The Roving Shadows, “That which claims not to be concealed is mere semblance.” With the appearance of his novel A Terrace in Rome, we can observe – and be delighted by — how this gesture plays out in an extended narrative. The story concerns Meaume the Engraver, born in France in 1617, who must spend his life loving what he has lost – a woman named Nanni. They meet when young; she is promised to another man. Nevertheless, they plan clandestinely and love passionately – until the other man spills acid on Meaume’s face disfiguring him for life. It doesn’t matter that I’ve told you this — A Terrace in Rome doesn’t depend on plot the way a suit relies on a hanger for shape.

In Abysses, Quignard writes, “All is not said.” That is, all cannot be said. And from The Roving Shadows, “That which claims not to be concealed is mere semblance.” With the appearance of his novel A Terrace in Rome, we can observe – and be delighted by — how this gesture plays out in an extended narrative. The story concerns Meaume the Engraver, born in France in 1617, who must spend his life loving what he has lost – a woman named Nanni. They meet when young; she is promised to another man. Nevertheless, they plan clandestinely and love passionately – until the other man spills acid on Meaume’s face disfiguring him for life. It doesn’t matter that I’ve told you this — A Terrace in Rome doesn’t depend on plot the way a suit relies on a hanger for shape.

Quignard traces Meaume’s itinerant life as he makes his living and enjoys his friendships. He works in various places in France and Italy, finally in Rome. There is much looking at things and people, remarks exchanged. Meaume’s engravings are described. All of Quignard’s obsessions emerge through the plangent narrative tone: time, desire, sexuality, love, art, imagery, mortality, spirituality, absence. Sometimes, Meaume utters something Quignardian: “One reaches an age when one no longer meets life but time. One ceases to see life as living. One sees time in the act of devouring life raw. One’s heart seizes up. One clings to driftwood just to see a little more of the spectacle bleeding from one end of the world to the other, and yet not fall in.”

A Terrace in Rome, which was published in France in 2000 and won the Prize of the Académie Française, is as exquisitely demure a work as I imagine Meaume’s engravings to be – technically perfect, crisp in detail, melancholic, and sometimes startling in its gaze. This is the story of Meaume’s life without Nanni. But Quignard wants the reader to participate in the profound loss. His terseness and brevity of chapters permits ease of entrance. What “happens” to Meaume along the way determines his actions and moves us to turn the pages – but he and we are lost in the passing of time. The fragmented narrative takes on the echoes of fable yet never betrays the world’s dire ways. Despite the strict economy of prose, one experiences a complete world and learns much about Meaume’s era and art.

Quignard writes in The Roving Shadows, “The person who writes is someone who tries to redeem what has been pawned.” He is trying to give us the actual lost thing that is there, on the page, nevertheless, silent.

[Abysses, published July 20, 2015, 256 pages, $25.00 hardcover.

The Hatred of Music, published March 22, 2016, 216 pages, $26.00 hardcover

A Terrace in Rome, published May 24, 2016, 128 pages, $13.95 paperback]

The Roving Shadows (2013) and The Silent Crossing (2011), both translated by Chris Turner as part of The Last Kingdom series, are available from Seagull Books.