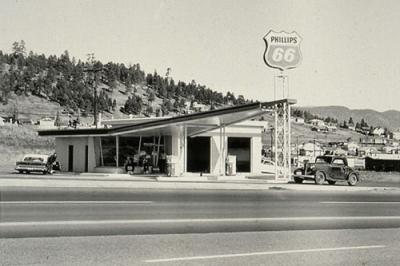

In 1963 at age 25, Ed Rusha (pronounced Ru-SHAY) produced 400 handmade copies of a photobook titled Twentysix Gasoline Stations. The textless content consisted of 26 black-and-white snapshot-style photos of gas stations. He sold the books for a few dollars each, insisting they were created to be ephemeral and “end up in the trash.”  Fifteen more photobooks of various subjects were created through 1972, employing the same production and distribution values.

Fifteen more photobooks of various subjects were created through 1972, employing the same production and distribution values.

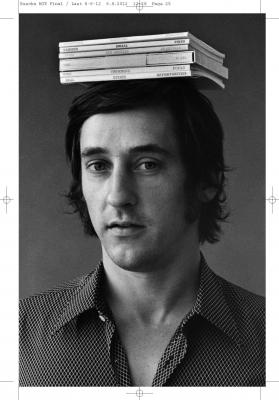

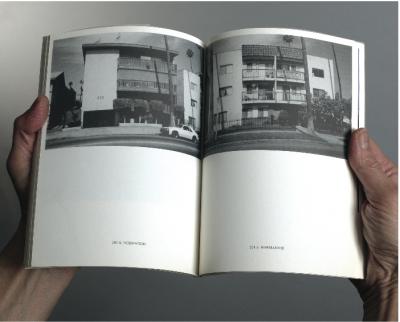

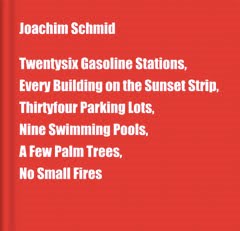

Since then, at least 100 accomplished photographers and artists have produced their own self-published photobooks copying Ruscha’s mode – imitating, celebrating, esteeming, and parodying the Ruscha archetype. Now, Various Small Books compiles cover art and sample layouts from 91 of those progeny, each one recycling the act of questioning the authority of photographic recording and having little interest in testing the limits of photographic technique – while somehow managing to enhance the audience’s field of vision.

Ruscha’s books seemed to be saying, “This is all there is.” The transmission of wisdom about things has been hollowed out leaving the shell of transmission, the grammar but not the statement. “I didn’t want to be allegorical or mystical or anything like that,” he said about Twentysix Gasoline Stations. “There is a very thin line as to whether this book is worthless or has any value,” an assessment which at least admits to the possibility of “value.” It was the renegade quality of the book itself, its ambiguous idea, that seemed to displace authority. But is it illegitimate to find a cold, reflective empathy in the shots, as if Ruscha was susceptible to their presence, so affected by the fact that critique became superfluous?

Ruscha’s books seemed to be saying, “This is all there is.” The transmission of wisdom about things has been hollowed out leaving the shell of transmission, the grammar but not the statement. “I didn’t want to be allegorical or mystical or anything like that,” he said about Twentysix Gasoline Stations. “There is a very thin line as to whether this book is worthless or has any value,” an assessment which at least admits to the possibility of “value.” It was the renegade quality of the book itself, its ambiguous idea, that seemed to displace authority. But is it illegitimate to find a cold, reflective empathy in the shots, as if Ruscha was susceptible to their presence, so affected by the fact that critique became superfluous?

In the early 70’s, several critics sniped at Ruscha’s work while others simply called him duplicitous, a cultivator of self-celebrity pretending a disinterest in trend-making. Was he mocking the artistic ambition or embodying and refashioning it? The enigma enraged certain critics. By 1983, Jan Butterfield in Images & Issues magazine was writing, “No Los Angeles artist has attracted more media attention over the years than has Edward Ruscha. although upon close examination, the public image created by Ruscha-watchers is as shifty as his art.” The artists who copied Ruscha, while seeming to underscore his work and status, simultaneously obscure them by adding layers of “the same.”

In the early 70’s, several critics sniped at Ruscha’s work while others simply called him duplicitous, a cultivator of self-celebrity pretending a disinterest in trend-making. Was he mocking the artistic ambition or embodying and refashioning it? The enigma enraged certain critics. By 1983, Jan Butterfield in Images & Issues magazine was writing, “No Los Angeles artist has attracted more media attention over the years than has Edward Ruscha. although upon close examination, the public image created by Ruscha-watchers is as shifty as his art.” The artists who copied Ruscha, while seeming to underscore his work and status, simultaneously obscure them by adding layers of “the same.”

The book may have been intended as short-lived, but it persists as a triggering concept with a cultish following, raising fresh questions about intentionality, copying, intellectual property, and the mind’s tendency – the shooter’s and the viewer’s – “to toggle between aesthetic and nonaesthetic judgments,” as Sianne Ngai has pointed out.

Photographer Jeff Wall once alleged that Ruscha’s photobooks “ruin the genre of the ‘book of photographs’” and obviate the photographer’s responsibility to critique the culture. But in the astute introductory essay to Various Small Books, Mark Rawlinson confronts, weighs and ultimately contradicts the many objections made to Ruscha’s books, while leaving a generous opening for further speculation by way of considering Ruscha’s heirs.

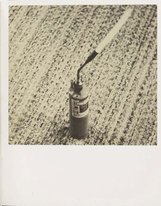

In 1964, Ruscha published the 48-page Various Small Fires and Milk, including photos of smokers, a lit book of matches, a burning candle, flaming trash, and at the end, a glass of milk beside the rim of a plate. In 2004, Jonathan Monk created & Milk (Today is just a copy of yesterday), a 64-page softcover, perfect bound edition of 800 copies. The was book created to supplement Monk’s exhibition small fires burning (after Ed Ruscha after Bruce Nauman after), during which Monk screened a film of Ruscha’s book going up in flames, page by page. About Monk’s book, Phil Taylor, who contributes the descriptive text of Various Small Books, writes:

In 1964, Ruscha published the 48-page Various Small Fires and Milk, including photos of smokers, a lit book of matches, a burning candle, flaming trash, and at the end, a glass of milk beside the rim of a plate. In 2004, Jonathan Monk created & Milk (Today is just a copy of yesterday), a 64-page softcover, perfect bound edition of 800 copies. The was book created to supplement Monk’s exhibition small fires burning (after Ed Ruscha after Bruce Nauman after), during which Monk screened a film of Ruscha’s book going up in flames, page by page. About Monk’s book, Phil Taylor, who contributes the descriptive text of Various Small Books, writes:

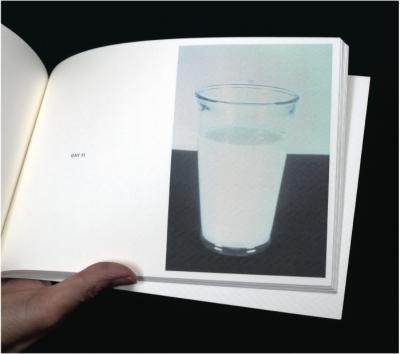

Quite simply, Monk began with a single photographic exposure of a glass of milk; the 50 illustrations that follow all stem from this one. Adopting a daily routine, the original slide of the glass of milk begat another that was reproduced from it, and then this second slide gave birth to another, and so on. Colors progressively change, details become muddled, and the framing of pictorial space shifts ever so slightly. The perfectly benign, if unexciting, glass of milk at the beginning is transformed into a sickly container of glue. Using the publication as a dumb flipbook can animate this change.

Quite simply, Monk began with a single photographic exposure of a glass of milk; the 50 illustrations that follow all stem from this one. Adopting a daily routine, the original slide of the glass of milk begat another that was reproduced from it, and then this second slide gave birth to another, and so on. Colors progressively change, details become muddled, and the framing of pictorial space shifts ever so slightly. The perfectly benign, if unexciting, glass of milk at the beginning is transformed into a sickly container of glue. Using the publication as a dumb flipbook can animate this change.

Some critics believe that Ruscha’s Some Los Angeles Apartments (1963, 34 plates) is his most seminal photobook. Last year, the Getty Museum mounted a Ruscha retrospective organized around the book’s fiftieth anniversary. In 1998, John O’Brian published More Los Angeles Apartments (48 pages, 1000 copies). But Taylor finds some crucial differences. “Structured as a short walk, O’Brian’s iteration functions more as an in-depth photographic survey of a specific location than a random assortment of disparate structures.”

It becomes clear that each of the 91 photobooks, while clinging to Ruscha’s example, finds a way to modify the original impulse. The notion of “the copy,” so palpable in the manufacture, gives way in various measures to invention and rebelliousness. Louisa Van Leer’s Fifteen Pornography Companies (2006) looks blankly at nondescript, anonymous buildings, while Julie Cook’s Some Las Vegas Strip Clubs (2008) “reveal the conventions of display and advertisement prevalent to the industry.”

It becomes clear that each of the 91 photobooks, while clinging to Ruscha’s example, finds a way to modify the original impulse. The notion of “the copy,” so palpable in the manufacture, gives way in various measures to invention and rebelliousness. Louisa Van Leer’s Fifteen Pornography Companies (2006) looks blankly at nondescript, anonymous buildings, while Julie Cook’s Some Las Vegas Strip Clubs (2008) “reveal the conventions of display and advertisement prevalent to the industry.”

When Ed Ruscha left his mother’s house in Oklahoma City in 1962, steering his 1950 Ford sedan toward Los Angeles on Route 66, he had resolved to begin taking photographs of gas stations along the way with his Yashica twin-lens reflex camera. He recalls, “The title came before I even thought about the pictures I like the word ‘gasoline’ and I like the specific quantity of ‘twenty-six.’” Did he ruin the photography book genre, revolutionize it, or merely tweak its nose? Ruscha insisted “I am dead serious about everything I make.” Premeditation was his mode.

Writing in Artforum, Philip Leider pronounced, “[Twentysix Gasoline Stations] is so curious, so doomed to oblivion that there is an obligation of sorts to document its existence, record its having been here.” A second edition of 3,000 copies was issued in 1970. On receiving a copy from the artist, the Library of Congress sent it back. (So he didn’t want it “to end up in the trash”!) Today it will cost you as much as $50,000 to acquire an original copy.

Writing in Artforum, Philip Leider pronounced, “[Twentysix Gasoline Stations] is so curious, so doomed to oblivion that there is an obligation of sorts to document its existence, record its having been here.” A second edition of 3,000 copies was issued in 1970. On receiving a copy from the artist, the Library of Congress sent it back. (So he didn’t want it “to end up in the trash”!) Today it will cost you as much as $50,000 to acquire an original copy.

In The Culture of the Copy, Hillel Schwartz asks, “Are we little else but futile reenactments, or is the reenactment the little enough that we can be truly about?” Various Small Books is enthralled by the question.

[Published by MIT Press on March 29, 2013. 288 pages, 298 color illustrations, 55 black & white illustrations, 6 x 9, $39.95 hardcover]

Re Ruscha

I shall not care

there are no poems

in gas stations, or

birds steal things

the sight unseen

not even missed

I close the book

of you, of photos

of what we saw

most is forgotten.