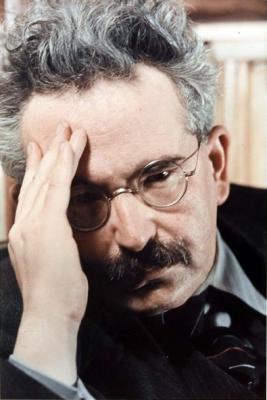

Walter Benjamin’s writings speak compellingly through their insistence that there is a latent history in everything we create, in all things made. The obstinacy and desperation of his life are harrowing to consider, just as his fierce intellectual independence is bound to inspire. About Proust and A la Recherché du Temps Perdu, Benjamin wrote, “He is filled with the insight that none of us has time to live the true dramas of the life that we are destined for.” In his work, Benjamin set an object before him and, as Susan Sontag said, “liked finding things where nobody was looking.” Thus it was in his work alone, in the sound of it, that he lived his destined life.

I began reading the works of Benjamin (1892-1940) after Carolyn Forché published her 1994 poetry collection, The Angel of History, with an epigraph from “On the Concept of History,” one of two iconic Benjamin essays studied widely today. The other is “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” and both were written near the end of his life. His writings are marked by their unmistakable style, described by J.M. Coetzee as “his trademark approach – coming at a subject not straight on but at an angle, moving stepwise from one perfectly formulated summation to the next.” Roberto Calasso has noted that Benjamin “was incapable of approaching a form without radically changing it,” thus introducing new ways of writing about history, art forms, and culture.

I began reading the works of Benjamin (1892-1940) after Carolyn Forché published her 1994 poetry collection, The Angel of History, with an epigraph from “On the Concept of History,” one of two iconic Benjamin essays studied widely today. The other is “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” and both were written near the end of his life. His writings are marked by their unmistakable style, described by J.M. Coetzee as “his trademark approach – coming at a subject not straight on but at an angle, moving stepwise from one perfectly formulated summation to the next.” Roberto Calasso has noted that Benjamin “was incapable of approaching a form without radically changing it,” thus introducing new ways of writing about history, art forms, and culture.

Then, there is the way Benjamin led his life, impulsively following his own insights and assertions, insisting on having everything his own way to the detriment of his academic career (ended when his doctoral thesis was rejected), his marriage and extended family life, many friendships, and his livelihood. Headstrong, imperious, severe in his judgments, depressive, and determined to radically change how we perceive time and history, Benjamin strove willfully (and at times obliviously) against the tide of German fascism and French collaboration. The story of his suicide by morphine in the Pyrenees is now legendary. To learn more about the man, one could dig up reminiscences by Gershom Scholem, Hannah Arendt and others, and read his selected letters.

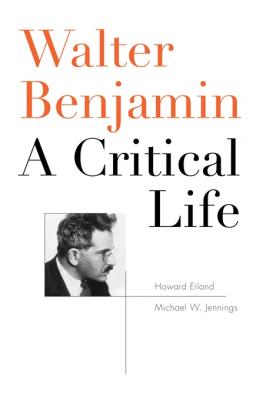

But now, his latest American biographers, literature and cultural theory professors Howard Eiland and Michael Jennings, have assembled a Benjamin afterlife that weighs and integrates his attributes, habits, ideas, life choices, influences, relationships (literary and erotic) and creative works in light of his milieu and world events. Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life sheds what light it can on the idiosyncratic strangeness of the person often regarded, as they write, as “one of the most important witnesses to European modernity … Yet for all the brilliant immediacy of his writing, Benjamin the man remains elusive. Like the many-sided oeuvre itself, his personal convictions make up what he called a ‘contradictory and mobile whole.’”

But now, his latest American biographers, literature and cultural theory professors Howard Eiland and Michael Jennings, have assembled a Benjamin afterlife that weighs and integrates his attributes, habits, ideas, life choices, influences, relationships (literary and erotic) and creative works in light of his milieu and world events. Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life sheds what light it can on the idiosyncratic strangeness of the person often regarded, as they write, as “one of the most important witnesses to European modernity … Yet for all the brilliant immediacy of his writing, Benjamin the man remains elusive. Like the many-sided oeuvre itself, his personal convictions make up what he called a ‘contradictory and mobile whole.’”

The dust may have settled from the turf wars over Benjamin’s legacy but his figure remains hard to discern within the enclaves that claim it. For 30 years, beginning with Theodor Adorno’s stewardship of a two-volume selection of Benjamin’s work in 1955 for Anglophone readers, various camps claimed Benjamin as their own – communists, socialists, theologians, journalists, philosophers, antiquarians, surrealists, existentialists, semioticians, structuralists, and postmodernists. By the mid-1980s, critics such as Richard Wolin persuasively argued for a Benjamin who visited (or was invited posthumously to) all the clubhouses but resisted membership or didn’t quite fit in. His messianic/theological tendency reached a détente with his wavering materialist/socialist usages.

Benjamin spelled things out in a 1931 letter to Max Rychner: “I’ve never been able to study and think except in the theological sense, if I may put it that way, that is, in accordance with the Talmudic doctrine of the forty-nine steps of meaning in every passage in the Torah. Now, my experience tells me that the most worn-out Marxist platitude holds more hierarchies of meaning than everyday bourgeois profundity, which always has only one meaning, namely apology.” Yet in his fastidiousness, industry, and unflagging politeness, he was very much the bourgeois man of letters, living off his parents and his wife into his thirties and traveling, however tenuously, through Western Europe.

Benjamin spelled things out in a 1931 letter to Max Rychner: “I’ve never been able to study and think except in the theological sense, if I may put it that way, that is, in accordance with the Talmudic doctrine of the forty-nine steps of meaning in every passage in the Torah. Now, my experience tells me that the most worn-out Marxist platitude holds more hierarchies of meaning than everyday bourgeois profundity, which always has only one meaning, namely apology.” Yet in his fastidiousness, industry, and unflagging politeness, he was very much the bourgeois man of letters, living off his parents and his wife into his thirties and traveling, however tenuously, through Western Europe.

But his opposition to his own middle-class background was unshakable. The biographers write, “One may find hope in the past, Benjamin suggests, only if tradition is wrested from the conformism working to overpower it, only if it is opened to the momentary standstill and sudden threshold of ‘messianic time’ – something beyond the casual nexus and chronological framework of modern scientific historicism. In the messianic experience of ‘universal and integral actuality,’ the present moment of remembrance is the ‘gateway’ of redemption, the revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed (or suppressed) past.” And later: “When what has been emerges in a lightning flash of recognition.”

After his rejection by academia, Benjamin strove to become Germany’s most important cultural and literary critic. In the late 1920’s, writing on deadline for journals and newspaper feuilletons, he gazed at a remarkable array of subjects – food, pornography, handwriting analysis, gambling, travel diaries, folk art, the writings of the mentally ill, film, photography, children’s literature, and much more. Benjamin’s genre-melding approach blurred the lines between prose fiction, memoir, reportage, cultural critique and oracular pronouncement. In his occasional pieces, one could find the most remarkable bursts of aphoristic commentary, such as this passage from a review of a history of toys:

After his rejection by academia, Benjamin strove to become Germany’s most important cultural and literary critic. In the late 1920’s, writing on deadline for journals and newspaper feuilletons, he gazed at a remarkable array of subjects – food, pornography, handwriting analysis, gambling, travel diaries, folk art, the writings of the mentally ill, film, photography, children’s literature, and much more. Benjamin’s genre-melding approach blurred the lines between prose fiction, memoir, reportage, cultural critique and oracular pronouncement. In his occasional pieces, one could find the most remarkable bursts of aphoristic commentary, such as this passage from a review of a history of toys:

Every great and profound experience would like to be insatiable, would like repetition and return to last until the end of all things, the restoration of an original situation from which it emerged … Play is not only a way for mastering terrible original experiences by softening, mischievously evoking, and parodying them, but also for savoring triumphs and victories with the greatest intensity, and always again … The transformation of the most upsetting experience into habit: This is the essence of play.

As Eiland and Jennings tactfully suggest in their chapter on Benjamin’s youth, the child’s playful “mastering” of experience carried into Benjamin’s most iconoclastic work. The child is captivated by the aura of the object and relates to it mysteriously. They write, “This notion – that a privileged cognition might be sparked by something inconspicuous and peripheral, whether in a text or in an image – goes back to Benjamin’s early writings.” The necessary belief, then, is placed in one’s own “privileged” cognition. Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life illuminates a solitary gesture of mind quite familiar to the contemporary poet and creative writer.

The biography tracks Benjamin’s relationships with a vast array of characters, placing emphasis on friendships with the three men who most profoundly affected his thinking: Scholem, Brecht, and Adorno. Scholem, the Kaballist scholar and Zionist who did not regard class struggle as the key to understanding history, cautioned Benjamin to preserve his fidelity to a theological core. For Brecht, Benjamin could never be enough of a Marxist. Adorno was his closest reader and most ardent supporter during the dire years before the war, but his advice on manuscript changes generated more of a mess from what was already a sprawling disorder, Benjamin’s unfinished opus The Arcades Project.

The biography tracks Benjamin’s relationships with a vast array of characters, placing emphasis on friendships with the three men who most profoundly affected his thinking: Scholem, Brecht, and Adorno. Scholem, the Kaballist scholar and Zionist who did not regard class struggle as the key to understanding history, cautioned Benjamin to preserve his fidelity to a theological core. For Brecht, Benjamin could never be enough of a Marxist. Adorno was his closest reader and most ardent supporter during the dire years before the war, but his advice on manuscript changes generated more of a mess from what was already a sprawling disorder, Benjamin’s unfinished opus The Arcades Project.

“History decomposes into images, not into narrative,” he wrote. One could claim, then, that the sturdy chronological narrative structure of Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life is hardly the history that Benjamin would favor. But the authors show that the rootedness of Benjamin’s habits of thought rages against decomposition, even as Benjamin’s writings revel in the fragmentary, bricolage, and the unglossed citation. All of his major works are covered here as well as some of his reviews and radio lectures and plays, though the authors could have shown more generosity in quoting from them and more restraint in reiteration. Frank Kermode said that Benjamin “is not a critic who goes in for ‘close analysis'” and John Berger noted that Benjamin “was not a systematic thinker.” But the biographers meticulously build a cogent structure for the evolution of his ideas, even if some of them, such as the “aura” he perceived in art objects, left even even his closest friends wondering if this was a trope, a kaballistic essence, or a delusion.

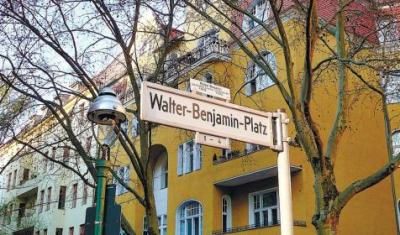

As Hitler assumed power in 1933, Benjamin recognized that his Berlin days were over. He wrote to Scholem, “There are places where I could earn a minimal income, and places where I could live on a minimal income, but not a single place where these two conditions coincide.” He went to Paris, and wrote again to Scholem: “Though many – or a sizable number – of my works have been small-scale victories, they are offset by large-scale defeats.” In exile, he produced his startling commentary on Kafka, writing to Scholem, “I endeavored to show how Kafka sought – on the nether side of that ‘nothingness,’ in its inside lining, so to speak – to feel his way toward redemption. This implies that any kind of victory over that nothingness … would have been an abomination for him.” One of the very moving aspects of this biography is its careful revelation of Benjamin’s nether side and his “venturesome identification with Goethe, Kafka, and finally Baudelaire.” The authors note, “We should remember that for Benjamin, thinking itself is an existential wager arising from the recognition that truth is groundless and intentionless, and existence a ‘baseless fabric.'”

As Hitler assumed power in 1933, Benjamin recognized that his Berlin days were over. He wrote to Scholem, “There are places where I could earn a minimal income, and places where I could live on a minimal income, but not a single place where these two conditions coincide.” He went to Paris, and wrote again to Scholem: “Though many – or a sizable number – of my works have been small-scale victories, they are offset by large-scale defeats.” In exile, he produced his startling commentary on Kafka, writing to Scholem, “I endeavored to show how Kafka sought – on the nether side of that ‘nothingness,’ in its inside lining, so to speak – to feel his way toward redemption. This implies that any kind of victory over that nothingness … would have been an abomination for him.” One of the very moving aspects of this biography is its careful revelation of Benjamin’s nether side and his “venturesome identification with Goethe, Kafka, and finally Baudelaire.” The authors note, “We should remember that for Benjamin, thinking itself is an existential wager arising from the recognition that truth is groundless and intentionless, and existence a ‘baseless fabric.'”

John Berger said of Benjamin as literary critic, “He never tried to seek simple causal relations between the social forces of a period and a given work. He did not want to explain the appearance of the work; he wanted to discover the place that its existence needed to occupy in our knowledge.” Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life may resemble a conventional biography in its structure and deft usage of secondary materials. But Eiland and Jennings also honor their subject by allowing Benjamin’s psyche to persist here as a mystery, to be more than the sum of causal relations. Benjamin’s aura, dim among the ruins, shimmers nonetheless. This book is a volume with use — a means of uncovering the place Benjamin occupies in our knowledge.

[Published by Harvard University Press on January 20, 2014. 768 pages, 36 halftones, $39.95 hardcover]