Israeli architects are a contentious lot. In July 2002, the Israeli Association of United Architects canceled its participation at the World Congress of Architecture in Berlin after the Israeli leadership rejected its own catalog for presenting a hostile view of settlements in the West Bank. The catalog was titled A Civilian Occupation: The Politics of Israeli Architecture. “But the Association is apolitical,” said its president. “Imagine if we did an exhibition praising the settlements.” Some 4,150 copies of the catalog were sequestered after 850 of them were spirited off by Eyal Eeizman, one of the two young architects who edited the banished catalog.

But the catalog was published soon after by Sharon Rotbard’s Tel Aviv-based Babel Publishers. The architect Zvi Efrat writes there that after 1948, Israel “put into practice one of the most comprehensive, controlled and efficient architectural experiments in the modern era … The pressing national task was providing temporary housing for the masses of new Jewish immigrants and settling the country’s borderlands, in order to stabilize the 1948 cease-fire lines, prevent territorial concessions and inhibit the return of Palestinian war refugees.”

But the catalog was published soon after by Sharon Rotbard’s Tel Aviv-based Babel Publishers. The architect Zvi Efrat writes there that after 1948, Israel “put into practice one of the most comprehensive, controlled and efficient architectural experiments in the modern era … The pressing national task was providing temporary housing for the masses of new Jewish immigrants and settling the country’s borderlands, in order to stabilize the 1948 cease-fire lines, prevent territorial concessions and inhibit the return of Palestinian war refugees.”

Rotbard, also an architect and a university lecturer in Israel and India, continued sparring with the establishment by publishing White City Black City in 2005. It is an unsparing and taut critique of the Israeli use of space – and a blunt and bracing history of Jaffa and Tel Aviv. Ten years old and now available in Orit Gat’s brisk translation, it has lost none of its edge and relevance.

Rotbard begins with events that occurred a year after the Berlin debacle. In July 2003, UNESCO’s World Heritage Commission recommended Tel Aviv for its list of World Heritage Sites. Nine months later, the “White City” celebrated its new honor with a series of events and exhibits. Having established a corporate hub, Tel Aviv could claim globally significant assets and innovation — but what of its “heritage”? The city answered: consider our Bauhaus personality.

Rotbard begins with events that occurred a year after the Berlin debacle. In July 2003, UNESCO’s World Heritage Commission recommended Tel Aviv for its list of World Heritage Sites. Nine months later, the “White City” celebrated its new honor with a series of events and exhibits. Having established a corporate hub, Tel Aviv could claim globally significant assets and innovation — but what of its “heritage”? The city answered: consider our Bauhaus personality.

The White City has now swallowed up its shadow, the Black City of Jaffa just to the south. The two were once a hyphenated city, Tel Aviv-Jaffa. But according to Rotbard, Tel Aviv “conquered and subjugated Jaffa, emptied it of its population, liquidated whole neighborhoods and expunged public offices. One city turned the other upside down. And in doing so, Tel Aviv also made war on Jaffa’s memory. This is a war which did not cease with the requisition of Jaffa or the exile of its Arab population in May 1948; it is one which continues unabated to this day.” The “Jaffa orange” may be Israel’s most recognizable product — but the Jaffa groves are gone. Oranges are grown everywhere but in Jaffa.

“It was written with anger,” he says of his book, “and the urge to bring justice to the city and to many of its people … to change the city just by telling the story in a different manner.” Where some see urban renewal, he sees confiscation and a deliberate erasure of cultural history. When the city’s tour guides describe the purity of the Bauhaus “style,” Rotbard finds a highly dubious architectural pedigree rooted in the belief of occidental superiority over the oriental. By detailing how Tel Aviv now uses Jaffa space, he persuasively suggests that its “blackness” is Israel’s own repressed psyche, “its dialectical negation.” His reasoning: only the one who isn’t white would so stubbornly try to prove that he is.

In a speech entitled “The Burden of Wilderness” delivered at the Jewish National Fund Conference of 1943, David Ben-Gurion named the two essential goals of Zionism. First, “the ingathering of the exiles” would provide safe harbor in a land considered to be the ancestral home of the Jews. Second, the future prime minister said Israelis would “rebuild the rubble of a ruined, abandoned country … that has remained in desolation for two thousand years.”

Five years later in 1948, it took the Irgun just a month to turn Jaffa into rubble and to send more than 100,000 Palestinians into exile, most fleeing south to Gaza. Having watched the Haganah take Haifa, the Irgun mortared the center of Jaffa and fought house to house against militias in Manshieh, the ancient Muslim neighborhood on the Mediterranean coast. According to Benny Morris’ account of the fighting in his book 1948, Ben-Gurion arrived in Jaffa two days after the city’s surrender to write in his diary, “I couldn’t understand: Why did the inhabitants leave?”

Five years later in 1948, it took the Irgun just a month to turn Jaffa into rubble and to send more than 100,000 Palestinians into exile, most fleeing south to Gaza. Having watched the Haganah take Haifa, the Irgun mortared the center of Jaffa and fought house to house against militias in Manshieh, the ancient Muslim neighborhood on the Mediterranean coast. According to Benny Morris’ account of the fighting in his book 1948, Ben-Gurion arrived in Jaffa two days after the city’s surrender to write in his diary, “I couldn’t understand: Why did the inhabitants leave?”

The first Jewish enclave of Jaffa, Neve Tzedek, was founded in 1887 through land purchase, though the Ottoman authorities restricted Jewish acquisition and even deported the Jews from Jaffa at the outset of the First World War. After the British eliminated those restrictions, Tel Aviv’s population grew from 2,100 in 1920 to more than 42,000 by the end of the decade. Meanwhile, the British themselves leveled a swath of land right down the middle of Jaffa, granted a separate township to Tel Aviv, and built basic infrastructure that ultimately served as a foundation for the new state of Israel. One of Zionism’s most cherished tenets is that, unlike European colonialism, it sought to colonize the land, not the population. But in Rotbard’s version, the Israelis merely completed the work and policies of British colonialists.

Rotbard’s narrative bristles with a Barthes-like sensitivity to signs; he specializes in the “punctum”that opens the visible to fresh perspective. For instance, a survey of the area shows that the Black City is actually the only area of greater Tel Aviv that evinces the internationalism claimed by the White City. Still, Jaffa (“a mute, deaf, and amnesiac city”) takes the brunt of Tel Aviv’s wrath:

“Everything unwanted in the White City is relegated to the Black City: all the inconveniences of metropolitan infrastructure, such as garbage dumps, sewage pipes, high voltage transformers, towing lots and overcrowded central bus stations; noise and air polluting factories and small industries; illegal establishments like brothels, casinos, and sex shops; unwelcoming and intimidating public institutions such as the police headquarters, jails, pathological institutes and methadone clinics; and finally, a complete ragtag cast of municipal outcasts and social pariahs — new immigrant, foreign workers, drug addicts and the homeless.”

“Everything unwanted in the White City is relegated to the Black City: all the inconveniences of metropolitan infrastructure, such as garbage dumps, sewage pipes, high voltage transformers, towing lots and overcrowded central bus stations; noise and air polluting factories and small industries; illegal establishments like brothels, casinos, and sex shops; unwelcoming and intimidating public institutions such as the police headquarters, jails, pathological institutes and methadone clinics; and finally, a complete ragtag cast of municipal outcasts and social pariahs — new immigrant, foreign workers, drug addicts and the homeless.”

Rotbard looks warily as well at other urban projects in the world such as the “wild urbanism” occurring in China. For him, the principle of equality of rights (“isonomy”) entails the preservation of memory within the city since identity discovers itself in those places. When “modern utopias and ancient beliefs … boil together with no precautions,” tensions ramp up. As I write this, Vladimir Putin is leveling the city of Grozny as part of his “anti-terrorism” campaign.

In 1998, Artforum International devoted an issue to “The White Stuff” — featuring an essay by Homi Bhabha titled “The Political Aspects of Whiteness.” The director of Harvard’s Humanities Center, Bhabha writes, “The subversive move is to reveal within the very integuments on ‘whiteness’ the agonistic elements that make it true unsettled, disturbed form of authority that it is — the incommensurable ‘differences’ that it must surmount; the histories of trauma and terror it is must perpetrate and from which it must protect itself; the amnesia it imposes on itself; the violence it inflicts in the process of becoming a transparent and transcendent force of authority.”

This “move to reveal” is the passionate gesture at the uneasy heart of White City Black City.

[Published by MIT Press on February 26, 2015. 256 pages, $24.95 paperback]

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In today’s news from Gaza:

During a recent secret visit to Gaza, the graffitist Banksy painted an image of the Greek goddess Niobe weeping for her slain offspring. A man named Rabie Darduna discovered the image on a framed door among the rubble of his house. After the artwork was publicized, Darduna was approached by some men who persuaded him to accept 700 shekels ($700) for the Banksy. Realizing that he had been swindled, Darduna has filed suit to regain possession.

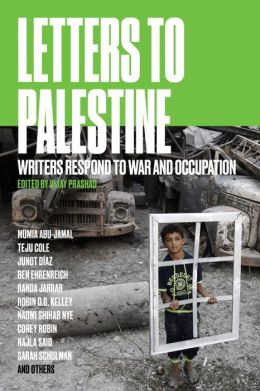

News out of Gaza becomes sparse after the shelling stops, or as the novelist Ben Ehrenreich puts it in his essay “Below Zero: In Gaza Before the Last War,” “The people of Gaza have been trapped, isolated, forgotten by the world — except when Israel chooses to bomb them with more than the usual fervor.” During the 50-day “Operation Protective Edge” last summer, 2,200 people were killed, 110,000 were displaced, and some 18,000 homes were destroyed. Ehrenreich’s piece is one of 27 works of prose and poetry in Letters to Palestine: Writers Respond to War and Occupation, edited by Vijay Prashad, a professor of international studies at Trinity College. Prashad has distributed the contents in three sections: Conditions, War Reports, and Politics.

News out of Gaza becomes sparse after the shelling stops, or as the novelist Ben Ehrenreich puts it in his essay “Below Zero: In Gaza Before the Last War,” “The people of Gaza have been trapped, isolated, forgotten by the world — except when Israel chooses to bomb them with more than the usual fervor.” During the 50-day “Operation Protective Edge” last summer, 2,200 people were killed, 110,000 were displaced, and some 18,000 homes were destroyed. Ehrenreich’s piece is one of 27 works of prose and poetry in Letters to Palestine: Writers Respond to War and Occupation, edited by Vijay Prashad, a professor of international studies at Trinity College. Prashad has distributed the contents in three sections: Conditions, War Reports, and Politics.

In addition to Ehrenreich’s essay, the first section also includes Noura Erakat’s “Travel Diary.” A human rights attorney and co-editor of Jadaliyya, Erakat remarks on a two-week trip in 2013 with an Interfaith Peace Builders delegation through the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Ordinarily in favor of “a more nuanced narrative and a more analytical inquiry,” Erakat yields to urgent, categorical terms in the diary. Nevertheless, she recognizes while in Ramallah that “the challenge is to articulate a critical perspective with constructive aims rather than paralyzing ones.” It is hard to do.

“Conditions” also includes “Imagining Myself in Palestine” by Randa Jarrar, an engrossing essay describing the author’s detention at Tel Aviv airport after arriving to visit family in Ramallah. I give nothing away by saying the Israelis put her back on a plane to the States. This is an essay about the agony of waiting in a non-place of one’s un-choosing, which is precisely what Palestinians have done for decades. It’s my favorite contribution to Letters to Palestine. There are also fine excerpts

“Conditions” also includes “Imagining Myself in Palestine” by Randa Jarrar, an engrossing essay describing the author’s detention at Tel Aviv airport after arriving to visit family in Ramallah. I give nothing away by saying the Israelis put her back on a plane to the States. This is an essay about the agony of waiting in a non-place of one’s un-choosing, which is precisely what Palestinians have done for decades. It’s my favorite contribution to Letters to Palestine. There are also fine excerpts

from Philip Metres’ poetry in A Concordance of Leaves (Diode Editions, 2013) “whose pages the wind rifles / searching for a certain passage.”

The heart of Part II, “War Reports,” is Najla Said’s moving and desperately observed “Diary of a Gaza War, 2014.” The ardency of her wishes goes a long way toward compensating for a naiveté toward geo-politics and extremism. Perhaps best known for her solo performance piece Palestine which ran off-Broadway in 2010, Said writes, “I abhor all violence. But I am also committed to the context of the situation.” The diary sticks to illuminating the context. News headlines launch her commentary. She quotes at length from Mahmoud Darwish, Peter Beinart, Lena Khalaf Tuffaha. Then, this entry, dated July 25:

“If anyone is still confused about the Middle East, here it is again, same explanation those of us who have been following it from over here for the last sixty-six years have been saying all along:

“1. It’s not about religion.

2. The Holocaust was perpetrated by Western Europeans, not Arabs.

In the same way opposing the war in Iraq doesn’t make you a bad American, criticizing the Israeli government doesn’t make you a bad Jewish person or an anti-Semite.

3.The only way to move forward is to recognize and accept each other’s rights to live as free human beings and figure out how to share the damn land.

4. Netanyahu needs a permanent psychological leave of absence.

5. Hamas runs Gaza the way a gang runs an inner city. Think about that and imagine what you’d do if you needed protection and had no water.

6. In light of all we talk about in America in terms of gun violence it all goes back to mental health and being hunan and kind and understanding one another.”

Part three, “Politics,” includes Robin D.G. Kelley’s “Yes, I Said ‘National Liberation” and Huwaida Arraf’s “This Is Not the University of Michigan Anymore, Huwaida.” The first is a declaration of solidarity with Palestinian resistance, and the latter covers Arraf’s co-founding of the International Solidarity Movement (ISM) in Jerusalem in 2001. There is also Sarah Schulman’s “What Is Anti-Semitism Now?” which never quite answers its own question except in the most superficial terms.

Part three, “Politics,” includes Robin D.G. Kelley’s “Yes, I Said ‘National Liberation” and Huwaida Arraf’s “This Is Not the University of Michigan Anymore, Huwaida.” The first is a declaration of solidarity with Palestinian resistance, and the latter covers Arraf’s co-founding of the International Solidarity Movement (ISM) in Jerusalem in 2001. There is also Sarah Schulman’s “What Is Anti-Semitism Now?” which never quite answers its own question except in the most superficial terms.

Among the documentary facts and the mounting of justified outrage, there are also a few lines of poetry here that stay with me — such as the final words of Fady Joudah’s “They Wake Up to a Truce a Fragment”: “Tonight / by flashlight / the living will spot / their survival unconcerned / with our kindness.”

[Published by Verso Books on April 14, 2015. 232 pages, $14.95 paperback]