Now in its sixth edition of 1,154 pages, David Thomson’s The New Biographical Dictionary of Film looks like a reference book. But it often reads like a collection of more than 1,400 droll job performance reviews. Here is part of Thomson’s newly added entry on Tina Fey:

“She is world-famous, but it all seems to slip off her cautiously groomed look. Has she ever done anything stupid, dangerous, or passionate? Has she any intention of trying? So in her determinedly old-fashioned look, she is somewhere between Elaine May and Lena Dunham but treating neurosis or mistake as Julia Child might have looked on Spam. She is overwhelmingly sensible, and a time may come when that is not enough, when Tina reveals pain, disaster, or madness. I don’t think it’s beside the point that she dresses horribly. So her famous ‘cool’ is not really cool at all.”

Criticized for his scrutiny of actors’ appearances, he responded in a Word and Film interview, “I do not see how in a medium like the movies that the actual look of people can be less than vital to what the movies mean and why those people are employed.” After all, appearances and pretense are all that an actor has to work with. Although he has produced 32 additional titles since 1967 on films and film people, in Why Acting Matters Thomson applies his unmistakable candor and compassion to illuminating “this gesture toward resemblance” called acting, on both stage and screen.

Criticized for his scrutiny of actors’ appearances, he responded in a Word and Film interview, “I do not see how in a medium like the movies that the actual look of people can be less than vital to what the movies mean and why those people are employed.” After all, appearances and pretense are all that an actor has to work with. Although he has produced 32 additional titles since 1967 on films and film people, in Why Acting Matters Thomson applies his unmistakable candor and compassion to illuminating “this gesture toward resemblance” called acting, on both stage and screen.

Born in London in 1941, Thomson has lived in the U.S. since the 1970’s when he taught film studies at Yale. Why Acting Matters speaks with a ripened sympathy for human foibles. “The enthusiasm for acting,” he says at the outset, “has come about because we have been drawn to pretense or avoidance beyond any hope for reality.” In both street life and stage acting, “if we are asked to pretend, there can be no question of an ultimate and reliable reality … people will perform, pretend, exaggerate, lie – all to the fine ends of the ‘company.’ How easily the language of theatre applies to regular, amateur life.”

And further: “We believe that these people are gentle liars and addicted pretenders. And in making these assumptions, we infer that the ‘others,’ the audience, are sober, honest, down-to-earth citizens whose worst instincts for dishonesty are exercised and even exorcised by the actors. Actors are the spokesmen for fiction itself in a world where we cling to the myth of fact.”

And further: “We believe that these people are gentle liars and addicted pretenders. And in making these assumptions, we infer that the ‘others,’ the audience, are sober, honest, down-to-earth citizens whose worst instincts for dishonesty are exercised and even exorcised by the actors. Actors are the spokesmen for fiction itself in a world where we cling to the myth of fact.”

Perhaps this accounts for the pathos of Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman in which the actor Riggan Thomson (played by Michael Keaton), successful as a superhero character in film, strives to perform an “authentic” performance on Broadway only to find oblivion closing in on him. David Thomson notes that such productions – plays or films about actors and acting – look back to Hamlet, “a play about the theatre and our failure to exist as more than amateurs playing ourselves.”

Thomson was schooled during the rise of film studies and the Cahiers du Cinéma critics in the 1960’s. But when asked about his influences, he responds with the names of great essayists – Joan Didion, John Berger, Gore Vidal, Greil Marcus, and Geoff Dyer. Each of the four chapters of Why Acting Matters is an impulsive, unpredictable and allusive essay, circling back to its main assertions. Although they are not exquisitely shaped in the conventional sense, the essays are inhabited by a compelling presence on intimate terms with his subject. The prose sparkles with lively discernment and anecdotal brio – yet he is willing to challenge his own enthusiasms. As a film reviewer for The New Republic, Thomson watches ten films a week.

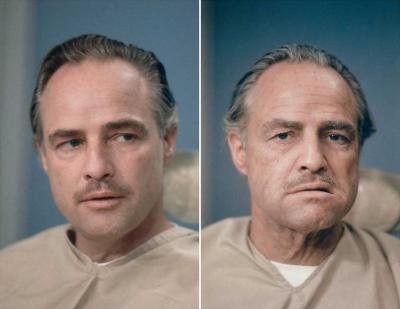

It may be difficult to imagine anyone other than Marlon Brando playing Don Corleone in The Godfather, but Thomson reminds us that Francis Coppola had seriously considered Laurence Olivier for the part. (Robert Mitchum, Ernest Borgnine and Frank Sinatra were considered as well – Sinatra?) “The standard for truth or realism in acting shifted so that many people saw Brando as more modern than Olivier,” he writes, “more in tune with rough, unschooled emotional existence.” But Thomson then takes issue with Method principles Brando picked up from Stella Adler (to possess the lifetime experience of the character). Since all acting is pretense, is it necessary or even safe for an actor to become so emotionally rooted in a role? Olivier’s wife, Vivien Leigh, suffered greatly during her film portrayal of Blanche Dubois alongside Brando’s Stanley – and won an Oscar.

It may be difficult to imagine anyone other than Marlon Brando playing Don Corleone in The Godfather, but Thomson reminds us that Francis Coppola had seriously considered Laurence Olivier for the part. (Robert Mitchum, Ernest Borgnine and Frank Sinatra were considered as well – Sinatra?) “The standard for truth or realism in acting shifted so that many people saw Brando as more modern than Olivier,” he writes, “more in tune with rough, unschooled emotional existence.” But Thomson then takes issue with Method principles Brando picked up from Stella Adler (to possess the lifetime experience of the character). Since all acting is pretense, is it necessary or even safe for an actor to become so emotionally rooted in a role? Olivier’s wife, Vivien Leigh, suffered greatly during her film portrayal of Blanche Dubois alongside Brando’s Stanley – and won an Oscar.

In 1989, while playing Hamlet in London, Daniel Day-Lewis became paralyzed and wept during a performance and had to leave the stage – not because he forgot his lines, but because his identification with the role made the lines irrelevant. He was Hamlet and therefore could be speechless. Brando seemed always to be on such a brink, “the pioneer of agonized hesitation in which nothing that can be uttered seems adequately genuine.” Ultimately, this disgust led to the demise of his career. “I doubt Brando needed to feel power or triumph as much as Olivier,” he writes. “But could Brando have captured the resplendent self-loathing in Olivier’s Archie Rice [in The Entertainer (1957)] without being ruined?” Olivier could exult in his remarkable range and supreme competence.

In 1989, while playing Hamlet in London, Daniel Day-Lewis became paralyzed and wept during a performance and had to leave the stage – not because he forgot his lines, but because his identification with the role made the lines irrelevant. He was Hamlet and therefore could be speechless. Brando seemed always to be on such a brink, “the pioneer of agonized hesitation in which nothing that can be uttered seems adequately genuine.” Ultimately, this disgust led to the demise of his career. “I doubt Brando needed to feel power or triumph as much as Olivier,” he writes. “But could Brando have captured the resplendent self-loathing in Olivier’s Archie Rice [in The Entertainer (1957)] without being ruined?” Olivier could exult in his remarkable range and supreme competence.

“The need for new roles is oddly akin to promiscuity,” Thomson remarks, one of his numerous telling one-liners. Another, related: “We all play with the list of roles that might have been ours.” One must pause to agree that “on some days, we spend more time with acted figures than with real people” – thus underscoring the question: why and how do they matter to us? He answers in many ways, including, “The pressure towards loss of identity increases all the time, and so the process of acting becomes more necessary as an assurance that we exist … Many of us know the desolation that only acting can keep at bay.”

Along the way, he touches on Orson Welles, Elia Kazan and Lee Strasberg, Meryl Streep, William Holden, Anton Chekhov, Gary Cooper, Shakespeare, Stephen Sondheim, John Barrymore and others (hmm, almost a total patriarchy). All of them provoke a singular inquiry: “Are we in control of the life we are leading, or does it occasionally run away with us? One reason we love actors is because we are so understanding of their professional predicament.”

[Published by Yale University Press on February 17, 2015. 192 pages, $25.00 hardcover]