The novels of Elsa Morante and Alberto Moravia rest side by side on the shelf of my local library. Moravia’s books are more numerous (he wrote more than 30 novels); Morante’s are thicker (she wrote four). Neither author is seeing much action. Moravia regarded his wife Elsa as the greatest novelist of their generation, and many Italian readers still agree with him. He was already famous in 1937 when they met, his novels were widely read and some would be transformed into movies. The first collection of her short stories was published in 1941, the year they married. He was a player in the literary scene, interwoven as it was with politics during the rise of Italian fascism and the post-war years of unstable governments and socialist activism.

Sensitive to slights, Morante bristled at any suggestion that her identity or writing were connected to her celebrated husband. One never addresed her as “Mrs. Moravia.” Morante was passionate and opinionated about art and character, but not politics; she mainly avoided her husband’s circle. He claimed never to have fallen in love with her. Although they were still married when she died in 1985, Moravia left Morante in 1962. Yet they lived together for years, took lovers, split up for periods. Both of them were half-Jewish. During the war, they fled Rome in 1943 (the Germans were looking for Moravia) and lived in hiding for nine months in a one-room hut above the village of Sant’Agata.

Sensitive to slights, Morante bristled at any suggestion that her identity or writing were connected to her celebrated husband. One never addresed her as “Mrs. Moravia.” Morante was passionate and opinionated about art and character, but not politics; she mainly avoided her husband’s circle. He claimed never to have fallen in love with her. Although they were still married when she died in 1985, Moravia left Morante in 1962. Yet they lived together for years, took lovers, split up for periods. Both of them were half-Jewish. During the war, they fled Rome in 1943 (the Germans were looking for Moravia) and lived in hiding for nine months in a one-room hut above the village of Sant’Agata.

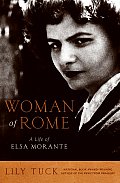

Lily Tuck hopes, in the introduction to Woman of Rome, that her new biography of Morante may renew interest in her novels among American readers. Morante’s uncompromising and unique artistic posture, and the stubborn habits and quirks of her character and behavior, make her an interesting study for both writers and readers. Placed against her period, she presents an alternative lens to the time’s history and culture – and its preference for social realism in fiction. But a broad revival in the U.S. seems unlikely – and Tuck herself supplies ample reason to hesitate. She describes Morante’s first novel, House of Liars (1948) as “a sprawling and confusing novel of over 800 pages … strangely anachronistic and lugubrious.” She backs away from Morante’s best-known novel History, writing, “large, sprawling, messy, ambitious, strange, History is difficult to judge.”

Lily Tuck hopes, in the introduction to Woman of Rome, that her new biography of Morante may renew interest in her novels among American readers. Morante’s uncompromising and unique artistic posture, and the stubborn habits and quirks of her character and behavior, make her an interesting study for both writers and readers. Placed against her period, she presents an alternative lens to the time’s history and culture – and its preference for social realism in fiction. But a broad revival in the U.S. seems unlikely – and Tuck herself supplies ample reason to hesitate. She describes Morante’s first novel, House of Liars (1948) as “a sprawling and confusing novel of over 800 pages … strangely anachronistic and lugubrious.” She backs away from Morante’s best-known novel History, writing, “large, sprawling, messy, ambitious, strange, History is difficult to judge.”

Inspired by the philosophy of Simone Weil, History is set in post-war Rome, an 800-page novel in eight sections, each part opening and capped with a narration of actual events. Tuck’s hedged comments on History seem to duck behind Robert Alter’s 1977 assessment when he wrote, “All that remains of historical experience is the pangs of victimhood; and those, after abundant repetition and heavy insistence, are likely to leave readers numbed – and with a sense that the sharpness of authorial indictment has finally been eroded by sentimentality.” Despite her singularity as an ambitious, highly independent female novelist, Morante has been forgotten by American readers and critics who favor the concision or modernity of Calvino, Buzzati, Pavese, di Lampedusa, or Eco. Her prose often reads like a literary analog of certain Italian films (Pasolini and Bertolucci were her friends, Visconti her lover) – spirited and gritty, sometimes magical or mythic in slant, sometimes dolorous or outraged.

A reconsideration of Morante would seem to require a motive or angle. Lily Tuck (b. 1938) knows something about both exile and Italy. Her German parents fled the Reich before the war and Tuck grew up in various places around the world. Her father, involved somehow in the movie business, took Lily to Italy in 1948. Once, she met Moravia – but not Morante, though she read the novels in English translation. “I read Arturo’s Island, Elsa Morante’s second novel, when it was first translated into English in 1959 while I was sunbathing on the beach in Capril (and, who knows, Elsa, who loved to sunbathe, might have been there as well) – not far from the island of Procida, where the novel is set. Right away Areturo’s Island became a sort of cult book among many American college students as well as one of my favorites … The novel surprised and shocked me, I had never read anything quite like it, and it made me curious about the author.”

A reconsideration of Morante would seem to require a motive or angle. Lily Tuck (b. 1938) knows something about both exile and Italy. Her German parents fled the Reich before the war and Tuck grew up in various places around the world. Her father, involved somehow in the movie business, took Lily to Italy in 1948. Once, she met Moravia – but not Morante, though she read the novels in English translation. “I read Arturo’s Island, Elsa Morante’s second novel, when it was first translated into English in 1959 while I was sunbathing on the beach in Capril (and, who knows, Elsa, who loved to sunbathe, might have been there as well) – not far from the island of Procida, where the novel is set. Right away Areturo’s Island became a sort of cult book among many American college students as well as one of my favorites … The novel surprised and shocked me, I had never read anything quite like it, and it made me curious about the author.”

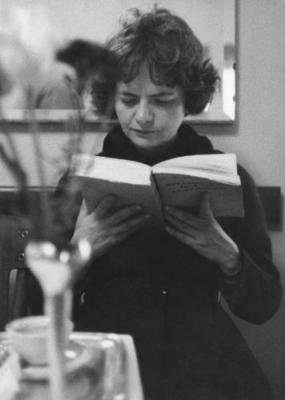

Tuck appears intermittently in her narration, turning up at different Morantesque locations. These cameos are hardly intrusive, but they don’t add value. The author’s personal quest for Morante could have played a more central role, had a psychological link between biographer and subject been explored, but perhaps none exists. Morante produced very little autobiographical writing and disliked being interviewed (she refused to appear on TV). She did keep a diary at times and Tuck quotes carefully from this source. But Morante left indelible memories with everyone who knew her, and their recollections form the basis of Tuck’s portrait of the writer. From these brief anecdotes and comments, a demanding, fun-loving, impetuous, generous, weakness-probing, truth-telling, hurtful, singleminded character begins to emerge.

Here are a few samples:

“People, Elsa Morante always claimed, were essentially divided into three categories: there was Achilles, the man who lived out his passions; there was Don Quixote, the man who, lived out his dreams; and, finally, there was Hamlet, the man who questioned everything. Moravia, in her opinion, was part Hamlet and part Achilles; she herself was all Don Quixote. In addition, she complained of Moravia’s ‘incurable detachment.’”

“Elsa was always testing people and hoping that by sort of ‘breaking them’ something strong would emerge.”

“Elsa was not someone who was envious. If she criticized you at all, she criticized you for your soul.”

“She had always, she wrote, cared tremendously about her body, its youth and perfection. At first she thought the reason for this was that she was waiting for love but now she realized that no one could truly love her. Her body’s decline and aging (she would turn forty in twelve days) and the loss of her beauty made her sadder, she wrote, than even the thought of her own death.”

“She was aware that apathy had become part of her nature, as had an increasing intolerance for other people … She found it increasingly difficult to communicate; in certain cases it had even become physically impossible. Most people hurt her feelings and it was she who was vulnerable. It was her fault, too, that she had never been loved, that she had no friends and that she was not happy.”

“Nor was Elsa a demonstratively physical person. She never kissed anyone and if someone tried to kiss her she drew back. As she grew older, she said that kissing her was like ‘kissing a rotten apple.’”

In the end, I was grateful to Tuck for not indulging in speculative psychoanalysis of Morante. The opening chapter on Morante’s youth is told in a straightforward fashion, though there is enough strangeness there to allow the reader to make one’s own connections as Morante evolves into a writer. Paraphrasing Morante’s friend, the poet Patrizia Cavalli, Tuck says “there must have been a very subtle kind if interior competition between the two writers [Morante and Moravia], a competition that rarely surfaced. In any case, Morante never wrote ‘against’ Moravia.” I see no reason automatically to concur. The two may not have competed in the marketplace where Moravia’s output was constant. But Morante, leaping from short stories (sometimes just a page in length) directly to widely-scoped novels, exceeded Moravia in sheer ambition. I would agree that she never wrote against him; in fact, they shared a liking for stories about relationships with an archetypal ring. Morante’s eye for enduring human qualities and situations set her apart from many other contemporary Italian novelists more likely to write books reflecting a social agenda.

In the end, I was grateful to Tuck for not indulging in speculative psychoanalysis of Morante. The opening chapter on Morante’s youth is told in a straightforward fashion, though there is enough strangeness there to allow the reader to make one’s own connections as Morante evolves into a writer. Paraphrasing Morante’s friend, the poet Patrizia Cavalli, Tuck says “there must have been a very subtle kind if interior competition between the two writers [Morante and Moravia], a competition that rarely surfaced. In any case, Morante never wrote ‘against’ Moravia.” I see no reason automatically to concur. The two may not have competed in the marketplace where Moravia’s output was constant. But Morante, leaping from short stories (sometimes just a page in length) directly to widely-scoped novels, exceeded Moravia in sheer ambition. I would agree that she never wrote against him; in fact, they shared a liking for stories about relationships with an archetypal ring. Morante’s eye for enduring human qualities and situations set her apart from many other contemporary Italian novelists more likely to write books reflecting a social agenda.

Her first novel, Menzogna e sortilegio (1948), literally “Lies and Witchcraft” but published in English as House of Liars, is a Sicilian family saga showing love as “a game of force and violence; the female dream of love is masochistic … and the male one is sadistic … She wrote about the nature of women with such mocking animosity.” In 1974 she published History, influenced by the Greek classics – and Weil’s perspective: “The human spirit is shown as modified by its relations with force, as swept away, blinded, by the very force it imagined it could handle, as deformed by the weight of the force it submits to.” And so, Robert Alter found the book dispiriting and merely outraged, not emotionally or intellectually complex. But Italian readership found much in the novel to debate. In the mid-1970s, the Italian Communist and socialist parties reached their peak of influence, and many on the left believed that the historic inevitability of Marxist solutions had arrived. Morante’s pessimism suggested otherwise. The intellectuals argued about the novel. Also, fascists didn’t care for it at all; Franco banned History in Spain. The book sold 800,000 copies in the first year.

Tuck does a splendid job of blending the life with the work. We see Morante’s daily routine at age 60, her messy apartment and her Siamese cats, her lunches and dinners with loyal friends and adoring younger people. But after completing History, she “became more and more reclusive,” writes Tuck. “She broke off with some of her friends and did not want to bother with casual relationships. She let her hair go white. When asked in a questionnaire what she considered to be the pinnacle of happiness, Elsa answewred, ‘solitude.’ When asked what she considered to be the pinnacle of unhappiness, Elsa answered the same thing, ‘solitude.’ The questionnaire also asked what she loved best in the world and Elsa replied the three M’s – in Italian, Mozart, mare, gelato di mandarino — Mozart, the sea, and tangerine ice cream.”

Tuck does a splendid job of blending the life with the work. We see Morante’s daily routine at age 60, her messy apartment and her Siamese cats, her lunches and dinners with loyal friends and adoring younger people. But after completing History, she “became more and more reclusive,” writes Tuck. “She broke off with some of her friends and did not want to bother with casual relationships. She let her hair go white. When asked in a questionnaire what she considered to be the pinnacle of happiness, Elsa answewred, ‘solitude.’ When asked what she considered to be the pinnacle of unhappiness, Elsa answered the same thing, ‘solitude.’ The questionnaire also asked what she loved best in the world and Elsa replied the three M’s – in Italian, Mozart, mare, gelato di mandarino — Mozart, the sea, and tangerine ice cream.”

Elsa Morante wrote that the purpose of art is “to prevent the disintegration of human consciousness in its daily, wearisome, alienating contact with the world; to continually give back to it, in the unreal, fragmentary, and consuming confusion of external relationship, the integrity of the real.” Her knowledge of the disintegrative forces was profound — corrosive family life, the fitfulness of love, poverty, war, mediocrity. How she converted that knowledge into art is the thing we can learn from – but we encounter that power only in biographical glimpses. Tuck gives us just enough insight to inspire a continuing interest in Morante.

[Published by Harper Collins on July 29, 2008. 249 pp., $25.95 hardcover]