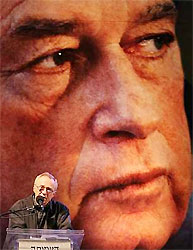

Forty-one per cent of the world’s Jews, or 5.5 million people, live in Israel. There are also 1.5 million Arab Israelis. In a country so small, prime ministers actually become acquainted with novelists and poets. Most of the writers have served in the military. “Writers in Israel play a role in the moral and political life of their country that is unfamiliar to writers in the United States,” writes Jeffrey Goldberg in “Is Israel Finished?”, the cover story of the May, 2008 issue of The Atlantic which focused on the contentious relationship between the now deposed PM Ehud Olmert and novelist David Grossman. On August 10, 2006, Olmert authorized the invasion of Lebanon. On August 13, Grossman’s son Uri, a tank commander, was killed in action in Lebanon by a Hezbollah missile. At the Yitzhak Rabin Memorial Rally on November 4, Grossman addressed 100,000 Israelis in Rabin Square in Tel Aviv. Olmert was also on stage. Goldberg writes, “Grossman refused to shake hands with the prime minister, but he directed his words at him.” A former mayor of Jerusalem, Olmert had known Grossman for many years.

Grossman’s speech, already widely accessible, is the final and briefest piece in his new collection of essays, Writing in the Dark. In the Rabin speech, Grossman asked, “How is it possible that a nation with our powers of creativity and renewal, a nation that has managed to resurrect itself from the ashes time after time, finds itself today – precisely when it has such huge military power – flaccid and helpless? A victim once again – but this time, a victim of itself, of its own anxieties and despair, of its own nearsightedness.” Then, he went after Olmert and his cabinet: “Look at the scared, suspicious, sweaty ways they behave, at their prosecutorial, deceptive conduct. It is ridiculous to hope that they might be the source of any inspiration.”

Grossman’s speech, already widely accessible, is the final and briefest piece in his new collection of essays, Writing in the Dark. In the Rabin speech, Grossman asked, “How is it possible that a nation with our powers of creativity and renewal, a nation that has managed to resurrect itself from the ashes time after time, finds itself today – precisely when it has such huge military power – flaccid and helpless? A victim once again – but this time, a victim of itself, of its own anxieties and despair, of its own nearsightedness.” Then, he went after Olmert and his cabinet: “Look at the scared, suspicious, sweaty ways they behave, at their prosecutorial, deceptive conduct. It is ridiculous to hope that they might be the source of any inspiration.”

The speech triggered Goldberg’s retrospective article on the seemingly irremediable issues in Israeli political life. But it is Grossman’s revealing 2004 essay, “Contemplations on Peace,” that more thoroughly portrays the knotty mentality of the country. Grossman carefully picks at the Israeli psyche, saying that for an Israeli to imagine peace is tantamount to believing there is a future – but that Israelis have lost the urge to exercise that capability. “It will be a huge challenge,” he writes, “to learn to live a life that is not defined by hostility, anxiety, and violence … the all-too-familiar tendency to approach reality with the mind-set of a sworn survivor, who is practically programmed — condemned — to define the situations he encounters primarily in terms of threat, danger, and entrapment, or a daring rescue from all these.” This is the orientation of Olmert in Goldberg’s article where he said, “Jews are not safer in Israel than they are in other parts of the world, but there is only one place that Jews can fight for their lives as Jews, as that is here.” Grossman’s responds that the obsession with death – the unabated fear of not surviving, “an eternal victim mentality” – robs the Israeli of humanity and rationality. He writes:

“Fifty or sixty years ago, the new Jewish settlement movement (the yishuv) in young Israel was prepared to make any sacrifice, because it felt that its purpose was singularly just. Whereas now, for significant components in Israel, the purpose no longer seems just; at times, it is not even clear what the purpose is.”

The Mediterranean is the only fixed border of Israel. All others have changed several times since 1948. “Living this way means living in a home where all the walls are constantly moving and open to invasion,” he writes. “The result of this ambiguity is that such a person’s identity is always on the defense.” To be overly defensive is to be overly aggressive. “The choices he makes in moments of distress or doubt are virtually doomed to be hasty and belligerent,” he says, adding the provocative notion that perhaps Jews actually prefer maintaining a borderless life among and within other nations. Obviously, Grossman is a proponent of completing a deal with the Palestinians. He describes his own “ ‘acquired naïveté … that knows full well what it faces and what it contends with.” In The Yellow Wind he critiqued Jewish settlers in the West Bank (“their houses are almost bookless … it is their complexity that is dangerous, not their simplistic willingness to follow their slogans”), so one wonders how he envisions uprooting these armed, messianic communities encouraged by past regimes to dig in.

The Mediterranean is the only fixed border of Israel. All others have changed several times since 1948. “Living this way means living in a home where all the walls are constantly moving and open to invasion,” he writes. “The result of this ambiguity is that such a person’s identity is always on the defense.” To be overly defensive is to be overly aggressive. “The choices he makes in moments of distress or doubt are virtually doomed to be hasty and belligerent,” he says, adding the provocative notion that perhaps Jews actually prefer maintaining a borderless life among and within other nations. Obviously, Grossman is a proponent of completing a deal with the Palestinians. He describes his own “ ‘acquired naïveté … that knows full well what it faces and what it contends with.” In The Yellow Wind he critiqued Jewish settlers in the West Bank (“their houses are almost bookless … it is their complexity that is dangerous, not their simplistic willingness to follow their slogans”), so one wonders how he envisions uprooting these armed, messianic communities encouraged by past regimes to dig in.

Writing in the Dark is subtitled “Essays on Literature and Politics,” but Grossman is simply no Kundera or Calvino. He writes about literature in an affirming mode with calm reflections on his background. His ideas are reasonable and perhaps predictable, his tone continually serious. There is an air of conventionality. “Books That Have Read Me” discusses how his early exposure to books (Schulz, Kafka, Woolf, Mann, Böll) resulted in his ability “to describe contemporary political reality in a language that is not the public, general, nationalized idiom.” His view of fiction writing connects to the themes of his more engrossing political essays: “Writing about reality is the simplest way not to be a victim.” If the Palestinian is the ultimate “Other” to the Israeli, then literature is a means of fully encountering and understanding that Other: “The desire to expose myself completely, without any defenses, to the individuality and life of another person, to his most elemental inner workings, in their unprocessed, primordial form” (from “The Desire to Be Gisella.”). In the title essay, he discusses language in terms of Israeli realities: “I feel the heavy price that I and the people around me pay for this prolonged state of war. Part of this price is a shrinking of our soul’s surface area – those parts of us that touch the violent, menacing world outside – and a diminished ability and willingness to empathize at all with other people in pain.”

Speaking from within the fortress mentality of Israel, Grossman has virtually no mental space for the essayist’s side trip, extended memory, or anecdote. A harsh reality has flattened his language into the elemental – which may sound bland to an American expecting to be entertained and impressed. In Israel, where the media is somewhat less intent on sucking into itself the people’s dumbed-down attention, his voice may actually be registered. Nevertheless, when asked to comment on Grossman’s charge that Olmert hadn’t done enough to remove outposts, the PM replied, “This is why I am prime minister and he is a writer.” Although Grossman warns against the victim’s mentality, his argument for literature — and against mass language — can only underscore how seriously endangered his voice is.

Speaking from within the fortress mentality of Israel, Grossman has virtually no mental space for the essayist’s side trip, extended memory, or anecdote. A harsh reality has flattened his language into the elemental – which may sound bland to an American expecting to be entertained and impressed. In Israel, where the media is somewhat less intent on sucking into itself the people’s dumbed-down attention, his voice may actually be registered. Nevertheless, when asked to comment on Grossman’s charge that Olmert hadn’t done enough to remove outposts, the PM replied, “This is why I am prime minister and he is a writer.” Although Grossman warns against the victim’s mentality, his argument for literature — and against mass language — can only underscore how seriously endangered his voice is.

In The Yellow Wind (1988), his account of visits to Palestinian camps and Israeli towns, Grossman noted the similarities between the symbol of the Irgun (the militant Zionist group operating in Palestine, 1931-1948) and the PLO: “Here a fist grasping a rifle against a map of the land of Israel, and there two fists, holding rifles, against the very same map.” Yet today, even after the death of his son, he writes, “I have a distant ally who does not know me, and together we are weaving this shapeless web, which nonetheless has immense power, the power to change a world and create a world, the power to give words to the mute and to bring about tikkun — “repair” – in the deepest, kabbalistic sense of the word.”

[Published by Farrar Straus & Giroux on October 7, 2008, 131 pp., $18.00]