On July 9, 1896, the New York Times ran a story alleging that the mayor of Long Island City was engaged in illicit activities. To provide evidence, the paper ran some photos, described by journalist Anthony Comstock as “snapshots.” Apparently, this is the first time “snapshot” was used to describe a photograph. The word had traditionally denoted a gunshot fired with negligible or no aim.

Only eight years earlier, George Eastman (1854-1932) and his Eastman Dry Plate Company produced the first affordable handheld camera, the Kodak. The first Kodaks cost $25.00 and had no viewfinder. By 1900, the Kodak Brownie sold for just one dollar and used Eastman’s flexible film (introduced in 1889) made of cellulose nitrate, a medium offering ease of print development, which in turn sparked a new service industry. In fact, the entrepreneurial birth of the film developing and printing industry was itself an early sign of century’s nascent “service economy.”

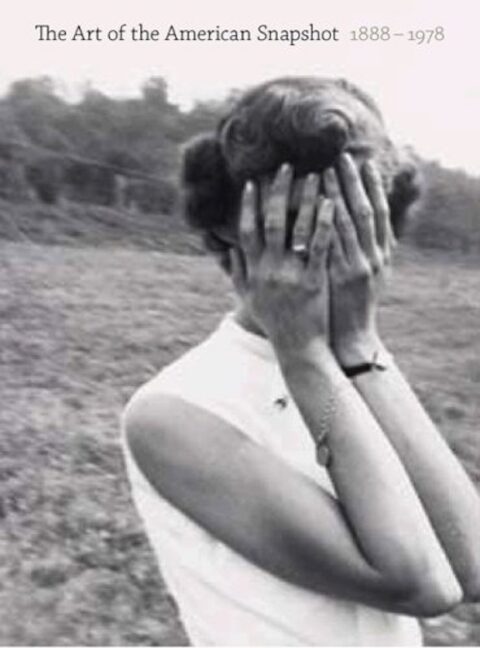

The impact of this commercialized technology on 90 years of American culture is the subject of The Art of the American Snapshot: 1888-1978, a fascinating consideration of the medium and its relation to changing modes of leisure, fine art photography, mass marketing, photojournalism, and twentieth century history.

The editors parcel the 90 years into quadrants. The first period, 1888-1919, is covered in Diane Waggoner’s essay, “Photographic Amusements.” During these years Eastman Kodak exerted such a hold on the mind of the American middle-class that it achieved complete dominance in its category for decades to come as the sole household brand for cameras and film. First came the many versions of the Brownie. In 1890, Eastman ran newspaper ads under the heading “Sporting Goods” with the pitch, “You push the button, we do the rest (or you can do it yourself).” The advertising tutored people to take pictures of certain subjects. Meanwhile, avant garde and fine art photographers learned from the casual nature of the snapshot and incorporated its qualities into their work.

The editors parcel the 90 years into quadrants. The first period, 1888-1919, is covered in Diane Waggoner’s essay, “Photographic Amusements.” During these years Eastman Kodak exerted such a hold on the mind of the American middle-class that it achieved complete dominance in its category for decades to come as the sole household brand for cameras and film. First came the many versions of the Brownie. In 1890, Eastman ran newspaper ads under the heading “Sporting Goods” with the pitch, “You push the button, we do the rest (or you can do it yourself).” The advertising tutored people to take pictures of certain subjects. Meanwhile, avant garde and fine art photographers learned from the casual nature of the snapshot and incorporated its qualities into their work.

During the second period, 1920-1939 as defined in Sarah Kennel’s essay “Quick, Casual Modern,” Kodak sent scouts along the country’s new highways in search of picturesque spots and vistas; they then posted signs stating “Picture Ahead! Kodak as you go!” Although “Kodak” was never adopted as verb, the Kodak camera and the language promoting it had a profound effect on the cultural values of the time. Eastman Kodak had long associated the camera with the satisfactions of family portraiture and depictions of rituals and sports. But increasingly, as Kennel points out, “Kodak began to stress use of the camera to counter the truancy of memory, particularly with regard to family stability.” The tagline “Let Kodak keep the story” first appeared in the early 1930s.

Sarah Greenough’s essay, “Fun Under the Shade of the Mushroom Cloud,” looks at the years 1940-1959, by the end of which over 70% of American families had a camera and produced more than two billion images annually. These were years in which anything became a subject. Kodak had introduced Kodachrome in 1936 and Kodacolor in 1942. Its marketing engine had succeeded in equating snapshots with sociability. Life magazine trained Americans to find narratives in pictorial journalism, and in 1957 NBC prefaced its programs with the voiceover, “in living color.” Snapshots provided Americans with an empowerment – a way to be producers of lively images while tides of imagery were spreading around them. Snapping pictures meant “modernity.”

In the final years of the snapshot’s primacy, 1960-1978, Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm film of the assassination of President Kennedy was presented to the public as a series of snapshots in Life (omitting the fatal head wound). The public and the private had collided. In 1963, Kodak introduced the Instamatic with its revolutionary film cartridge, and by 1970 had sold 50,000,000 units. The Polaroid camera, promising instant gratification, complemented the booming market for TV dinners. Although its marketing language merely echoed Kodak’s messages, by 1974 the Polaroid SX-70 produced one billion instant pictures a year. “It is the period when daily life, turned by a nation of consumers into an unending succession of narcissistic photo ops, becomes fodder for media spectacle, creating the lottery-like promise of instant but evanescent celebrity for everyone,” writes Matthew Witkovsky in the final essay, “When the Earth Was Square.” “These are the years when nothing is sacred yet everything is ritualized; when no one and everyone is special, and all things are made potentially interesting in pictures; and when amnesia, which thrives on prosperity, takes, hold, leaving memory to scatter and fade in billions of little prints.”

A thing of the past, the snapshot gives way to the digital image captured on a cellphone, deleted to clear storage space for more temporary pictures. The act now repeats a contemporary gesture: affirming the surface of things alone. Where the snapshot seemed to be about thingness, the digital image is often about the victory of time over things. When David Ortiz comes to bat in the ninth and all of Fenway Park yells for a walk-off homer, the stadium emits a wraparound flash as the pitcher delivers. The image travels to thousands of others to say: Sox win and I was there. Game over, delete. The world of amateur images and the world of corporate images have merged, just as “reality” of unscripted (but heavily directed) lives is integrated with primetime network TV programming. The ultimate reality show of our time is composed of digital images taken at Abu Ghraib prison. A few months ago I heard Errol Morris discuss his film-in-progress on those pictures; it seems that our culture’s orientation to the image, the lost boundary between private and public, may have been as much of a factor as the sheer violation of moral sense and army procedure. The companies that make our photo equipment no longer urge us to preserve our private lives; they conspire to make us disappear into the trillions of surfaces of the networked world.

This wonderful book slows things down, if only to let us gaze at the many snapshots presented here. Accessing images from the collection of Robert E. Jackson, the editors draw our attention to “snapshots that break down the barriers of time, transcending their initial function as documents of a specific person or place, to speak with an energy that is raw, palpable, and genuine about the mysteries and delights of both American photography and American life … Honest, unpretentious, and deeply mesmerizing, they show us moments of simple truth.”

Inevitably, one thinks of the snapshots, analog and digital, in our family albums and desk drawers. My own powder blue Brownie, circa 1961, is cradled in its original Kodak yellow box. When I received it as a birthday gift, I became the family’s snapshooter. My father, who had taken snapshots only when I was a toddler, stopped taking movies. Similarly, I stopped taking pictures when my daughters assumed the role. Kodak may have ingrained in us the shame of not preserving the images of ourselves, but for some of us giving up the endless preoccupation of preservation comes as a relief.

In addition to tracking consumer trends and cultural emphases, the essays have a great deal to say about the snapshots themselves. For instance, Witkovsky explains the language of the square snapshot prints of the 1960s and 1970s. “The square shape supplants narrative flow with iconic status,” he writes, “and it trends to draw attention away from the picture toward the object as such.” His notes on the “implicit resistance to storytelling” in these images remind me of the erosion of narrative rhetoric in the poetry of the period.

The snapshots printed here are unique. The editors haven’t attempted to recreate the actual qualities of the typical period photo album. And yet “those cars, clothes, even the gestures beneath the hairdos seem intimately familiar,” as the photographer Rich Rollins told me.]

[Published by Princeton University Press and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2007, $55.00, 288 pages, 278 color and duotone illustrations.]