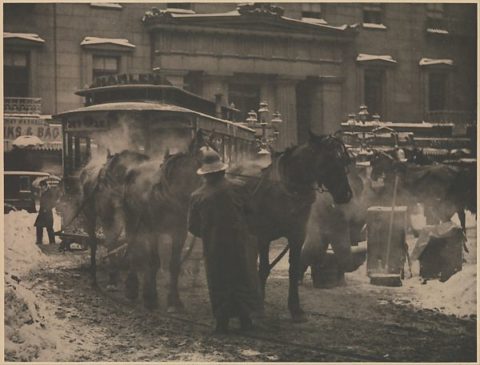

The Terminal

—After Alfred Steiglitz’s photograph, 1893

Because what’s cropped from the scene is

everything, really — Gibson Girls with frizzled bangs

finally ditching their corsets, the wooden pegs

aging Civil War vets used to prop their phantom

legs clicking their last down the cobblestone,

your President hiding a bloom of

cancer in his mouth. Even your dear

Georgia — the love for which we all know you

now — well, she was still a child humming

her alphabet down a dirt road, miles and miles away.

And you, Alfred, no, I can’t see you either:

like a minor god off in the corner

of his creation, you’re invisible but the perspective’s

yours. I can almost conjure you back, back when

you were all moustache, a tall drink of dark

ale shuffling around the city until you

found this — an image — one worth keeping, a scene

of a blizzard finally settling outside you and within.

Oh, you remember the one: that shot you took

with a brand new invention that used aperture to make

artifact, the shot taken at the city’s Southernmost

station where the horses, those drudges that lugged

the Number Sixteen to Harlem and back took respite,

a brief Sabbath when the trolley finally

stopped and buckets of fresh water were brought.

You remember what you said, right? How you yearned

to capture something quotidian as the weather

and how disconsolate you were — a sorrow alleviated

when you saw that driver in a rubber coat caring

for his team in the bitter cold, because there, at any rate,

is the human touch. It was pathetic fallacy

alright: you, the gloomy artist, stopping to use

the magic of your little black box to immortalize

your own loneliness, capturing the prayer made

when those veils of exhaustion became

visible, steam ghosting off the sour-wet backs

of the overworked. Yes, you made the story

your own as if that was all that existed

that night, because you and I both know

art is made from what is

left out as much as anything else.

*

And what’s cropped too is a truth

you surely knew, that of these horses —

how they’d have at best three years

to live before they dropped

dead on the street, and too big to lift, they’d be left

to rot until they were soft enough

to hack apart and carry off in manageable chunks.

Not pleasure horses but street nags, they were the original

American horsepower, garaged in lower

tenement flats cramped dark with rats, fueled with

cheap oats and a whipping stick. The year after

you took that photo, a hundred thousand of them

were in your city alone, a year known for

The Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894, and though

the blizzard that night brought enough

white to cover all that shit, once that snow melted,

the liquefied sludge of it wicked up the hem of every

long skirt, brought on a plague of flies in spring.

And yes, even then, much was the same:

the bulk of it was shoveled from rich neighborhoods

and dumped into the streets of the poor, making their roads

into a fetid river so thick with epidemics

a state of emergency was declared, demanding

another new invention — the horseless carriage — a thing

electric and motor and — most of all — clean —

to bring you and yours into a new age.

The rest? History, of course, with the endless

firings and exhaust of these past thirteen decades

to come, but before we savor that

irony and go there, let’s not forget

those horses, Alfred, how once those cars rolled

off the assembly, those horses were

worthless, made into meat

cheap enough to use as chicken feed.

*

I tell you this because last October

my mama called to tell me it was a hundred degrees

in Kentucky, that green valley I once knew

as home. She paused, said, Baby, funniest thing.

I was out there on my porch, having my coffee as usual,

and well, I couldn’t hear a thing, by which she meant

the birds, how in the freakish heat this autumn

they had nothing more to say.

I tell you this because when she asked

what I thought, I made up some lie

about a head start on migration, because damned

if I was going to tell a woman about to spend

eight hours on her feet the fact that

even our insects are dying out now.

I tell you this because you’d be shocked

to see what’s become of the weather — what was once

an old-folks, fine-how-you exchange, a tipping-hat pleasantry,

is now twenty-four-hour, storm-team channel,

whole seasons renamed

tornado and hurricane, mudslides and fires wiping out

entire towns in hours, and nobody in their right mind

trusts the stack of almanacs gathering

dust at the hardware store.

You’d also be floored to see cameras

common as kerchiefs once were, and just yesterday,

my mama texted me a photo when she took the kids

to a pumpkin patch and touched the first horse she’d seen

in years. In the shot, she’s pressed her palm to the dappled

muzzle, and leaning into the fence, you can tell she’s breathing in

all the sweet green rising from that barn, breathing the velvety

warmth of that beast, and if you look close, you can almost see

the dim light of another small prayer, the one she placed

on that mare’s face. I tell you this because

her photo, too, was taken at a terminal, but it’s no

station, no place to rest. No, Alfred, think incurable,

an ash-colored tumor choking out the lungs, each breath

taking in less oxygen, the blood fizzling with

carbon. Better yet, think of your passenger pigeons, your bison,

of those horses — there were so many of them they were once

a nuisance, an endless supply, and now? Well, what are left

only make a special appearance — a treat, like that single horse

with no work to do except

pony-ride the kiddos in circles and stitch

my exhausted mother

back to herself. I tell you because what’s cut

from the image she sent me is, you know, still the same:

everything to come and everything

past. I’ve stared at it the way I stared

at yours, tricked by how a single click stops time,

desperate to know how a camera can do that and still do

nothing to stop what is to come. For that,

I give her photo the same title

as yours, because both mark their own

separate beginnings to this same end.

Ø Ø Ø

This poem was originally commissioned by the Poetry Center at Smith College for the book The Map of Every Lilac Leaf: Poets Respond to the Smith College Museum of Art.

This poem was originally commissioned by the Poetry Center at Smith College for the book The Map of Every Lilac Leaf: Poets Respond to the Smith College Museum of Art.