Welcome to the Seawall’s annual fall poetry feature. Below, twenty poets write briefly on some of their favorite new and recent collections. This multi-poet/title feature is posted here annually in April and December.

The commentary includes:

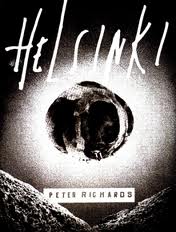

David Rivard on Helsinki by Peter Richards (Action Books)

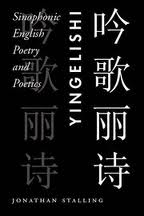

Hank Lazer on Yingelishi by Jonathan Stalling (Counterpath Press)

Elaine Sexton on Black Blossoms by Rigoberto Gonzalez (Four Way Books)

Nick Sturm on I Am Not A Pioneer by Adam Fell (H_NGM_N Books)

Anna Journey on Money for Sunsets by Elizabeth J. Colen (Steel Toe Books)

Michael Collier on Coral Road by Garrett Hongo (Alfred Knopf) and Sand Theory by William Olsen (TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press)

Jennifer Barber on Ghost in a Red Hat by Rosanna Warren (W.W. Norton)

Joshua Weiner on Complete Poetry, Translations and Selected Prose by Bernard Spencer (Bloodaxe Books)

Amanda Auchter on The Lifting Dress by Lauren Berry (Penguin)

Brian Teare on Kintsugi by Thomas Meyer (Flood Editions)

Barbara Ras on Dogged Hearts by Ellen Doré Watson (Tupelo Press) and Transfer by Naomi Shihab Nye (BOA Editions)

Rusty Morrison on Flower Cart by Lisa Fishman (Ahsahta Press)

Daniel Bosch on Heavenly Questions by Gjertrud Schnackenberg (Farrar Strauss Giroux)

Randall Mann on Red Clay Weather by Reginald Shepherd (Pittsburgh)

Julie Sheehan on All Of Us by Elisabeth Frost (White Pine Press)

Philip Metres on Toqueville by Khaled Mattawa (New Issues)

Dora Malech on Le Spleen de Poughkeepsie by Joshua Harmon (University of Akron Press)

Aaron Belz on Things Come On by Joseph Harrington (Wesleyan)

Victoria Chang on Sanderlings by Geri Doran (Tupelo Press)

Daniel Lawless on Kindertotenwald by Franz Wright (Alfred Knopf)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by David Rivard

Helsinki by Peter Richards (Action Books)

No form would seem more at odds with the ellipticism and fragmentations of our current period style than the epic poem. An aesthetic whose primary effect is that of simultaneity, and whose pleasures are those of chance and receptivity, makes an unlikely vehicle for story. The audacity of Peter Richards’ Helsinki is that it subverts the accepted wisdom that narrative is either unnecessary or impossible when composing with methods that are “indeterminate.”

The result is a book filled with duende, one of the very few written in the last twenty years that could be said about. Composed in densely lyrical, fairly brief sections, Helsinki begins with what initially sounds like a strange field report written during debriefing. “In time” is the phrase that kick starts the action, an idiomatic eternity that cannot be escaped:

In time I came to see death was the hay

binding one soldier to another and my own

death would appear partially lit as during

a nighttime operation the moon barely attends

whereas I with new density carry on as before

That wildness and richness of vision runs throughout, but the character of the narrator so established in these lines anchors it in a psychological complexity—vulnerability, rage, fear, tenderness, bafflement, melancholia, disdain, awe, and horny self-amusement are churned through with a rapidity driven by musical invention but somehow wholly consistent in how it is all the speech of single person.

That wildness and richness of vision runs throughout, but the character of the narrator so established in these lines anchors it in a psychological complexity—vulnerability, rage, fear, tenderness, bafflement, melancholia, disdain, awe, and horny self-amusement are churned through with a rapidity driven by musical invention but somehow wholly consistent in how it is all the speech of single person.

Robert Duncan once complained that the LANGUAGE poets had failed because they had no stories to tell. Duncan might have been pleased by the obsessive-compulsive mythologizing of Helsinki’s character-filled underworld, with its tenderhearted berserker soldiers, its tentacled erotic starlets, metabolizing bees, and “loose cloud/of animal gadgetry eating air and chrome alike.” An air of perverse Ovidian transformations hangs over Richards’ landscape, transformations that are intended to uncloak rather than disguise:

It’s one of the qualities underground

we each appear indelible visible

precisely as ourselves …

The story, as Richards describes it during readings from the book, is about an anonymous army officer—a war criminal—who has died during a campaign, though he often seems unaware of his death. The action sometimes occurs in this soldier’s past and sometimes in an undetermined future. Often, it’s hard to tell if the events are taking place in classical antiquity or a Nordic Middle Ages or a post-apocalyptic empire or Fallujah circa 2007 (and this ambiguity will certainly annoy some readers). In fact, everything might be happening within the inexplicably surviving consciousness of this dead soldier—if this sounds like a science-fiction fantasia, oddly enough it doesn’t come off that way in the telling. “I’m just someone caught up in the need for air,” the narrator says; and he’s a sort of enigmatic everyman trapped in events that echo uncomfortably with our own moment in time.

In one of the earliest sections, one particular passage reads like a first-hand account of an atrocity that could be bylined either Ciudad Juarez or Helmand province. What’s feels unique and personal (not to mention shocking) is the mix of ritualized tribal revenge killing with tender erotic memory and thuggish bravado:

When we came upon this large orange hide

staked to the ground by three orange feathers

I knew one of our boys lay headless beneath it

but from the air who could tell he was one

of my own or that I would come to remember

his face what restraint he brought to my tent

at night his anxiety that seemed to smile upon

me same way a white dot begins to ripen inside

this one mountain of Nice a face of sad orange

decorative stone where I lay surviving the prattle

but losing the kiss until finally I gave his name

to the mountain the campaign all night the full

story how for sixteen hours I hung from the beams

of the parliament ceiling and while the jeering

population looked on I could hear in the blackout

the plan for one day holding their lives in my hand

“The basic outline of my story is evil,” admits the narrator, which isn’t to say that it’s unremittingly brutal and horrifying. Helsinki swerves frequently into the erotic life of its speaker, often with a weird humor all its own. The center of that life is a woman named Julia, who might best be described as a dominatrix disguised as an iridescent hummingbird born from a discarded horseshoe:

I could say she was an extraordinarily practical green flying horse

such was the thrift by which she enjoyed warming her body

at the hearth of its own luminosity…

Sometimes vengeful and cruel, Julia is almost always willing to get it on with creatures both human and nonhuman. Her handmaiden is a fantastic, tentacled, multi-nippled monster with “the balls of a horse but the face of a girl,” who the narrator refers to as a “herrick.” In the end, Helsinki’s blend of eroticism and humor may be as alarming as its air of violence and rampage.

Sometimes vengeful and cruel, Julia is almost always willing to get it on with creatures both human and nonhuman. Her handmaiden is a fantastic, tentacled, multi-nippled monster with “the balls of a horse but the face of a girl,” who the narrator refers to as a “herrick.” In the end, Helsinki’s blend of eroticism and humor may be as alarming as its air of violence and rampage.

One might say that a reader is “immersed” rather than given a path through Helsinki’s rich underworld. At times I wished that Richards had provided more of the direct framing that he gives listeners at readings. A little more back-story and connective tissue would not destroy the complexity of the book, and the gain in narrative clarity would have been a plus.

Nonetheless, whatever demands Helsinki makes of a reader are bound up with its ultimate seriousness and Richards’ risk-taking as a writer. While its method of composition can hardly be described as avant-garde (its use has been around at least since Apollinaire’s Alcools, and the aesthetic is widely practiced by contemporary poets of various generations), Richards does seem to have accelerated its processing speed. Thanks to his syntactical deftness, one feels carried by the music of that processing.

Peter Richards’ method suggests a view of time and space similar to that of Bell’s Theorem, a theory of quantum mechanics that states that previously “entangled” systems and particles may continue to exert influence on and communicate with one another even when separated by light years. The phrase sometimes used to describe this is “spooky action at a distance.” It fits Helsinki to a tee.

(Published April 1, 2011, 90 pages, $16.00 paperback)

David Rivard is the author most recently of Otherwise Elsewhere (Graywolf Press) – reviewed here by Ron Slate. He teaches in the University of New Hampshire’s MFA in Writing Program.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Hank Lazer

Yingelishi: Chanted Songs Beautiful Poetry by Jonathan Stalling (Counterpath Press)

If we say that the 21st-century belongs to China, we probably imagine that we have made an observation that is principally an economic statement. I think that such a perspective misses the boat. In fact, the slow boat not to but from China is linguistic. Yingelishi is a remarkable work and perhaps the most astonishing first arrival – a scouting party – for the more substantial boat that is surely on the way.

If we say that the 21st-century belongs to China, we probably imagine that we have made an observation that is principally an economic statement. I think that such a perspective misses the boat. In fact, the slow boat not to but from China is linguistic. Yingelishi is a remarkable work and perhaps the most astonishing first arrival – a scouting party – for the more substantial boat that is surely on the way.

Stalling’s odd book takes up residence at an intersection of two languages, “as Chinese makes a home in English, / becomes English / without having stopped being Chinese.” As Stalling’s introduction informs us, “On any given morning, / hunched over on benches / or pacing back and forth, / students in China are reading English aloud from textbooks.” Yingelishi: Chanted Songs Beautiful Poetry makes poetry out of this unique moment of fusion, collision, and collaboration – “the opening of Chinese vibrations/ beneath the surface of each English word.” Such a moment and location of intersection, though, is not merely one person’s uncannily perceptive poetic construct. In fact, in China today “more people are studying English than there are Americans alive (over 350 million).” It is literally true that there are more speakers of English in China than in the US, and that the putting of English into Chinese characters (and thus the sounding of English in another language), Sinophonic English, is itself becoming “a significant global dialect of English.” As Marjorie Perloff has observed of Yingelishi, ‘it is a book that is “pointing the way to what a truly global poetry might look like.” The result, as Michelle Yeh notes, “is nothing short of magic.”

Stalling’s book of poetry successfully avoids becoming merely a humorous annotation of the oddities of this homophonic immersion in English. His book is no gimmick; it is not a simple display case for Chinglish or for the Charlie Chan-like pseudo-pidgin that gets mocked in popular cinematic culture and elsewhere. Stalling’s poetry comes out of more than ten years of experimentation and composition (after Stalling, who began studying Chinese as a middle school student in Arkansas, became fluent himself in Chinese). The resulting book of poems truly cannot be adequately explored in this brief review, for the book is remarkable in many ways. Even as Stalling explores the material of standard language-learning textbooks, the storyline that emerges, particularly in Traveling, the concluding section of the Yingelishi, is painful and emotionally moving. Other pages achieve their own engaging lyricism and wisdom. In an overarching way, Stalling’s Yingelishi is an important document in what might be labeled as an emerging transpacific poetry and poetics, or a transpacific imaginary, a field where the writings of Yunte Huang assumes a pre-eminence (his critical book Transpacific Displacement, but also the book of poems Cribs and the translations in SHI as well as Huang’s more recent book on Charlie Chan), and includes as well Rob Wilson’s writing, Susan Schultz’s Tinfish Press and journal and Glenn Mott’s book of poems Analects.

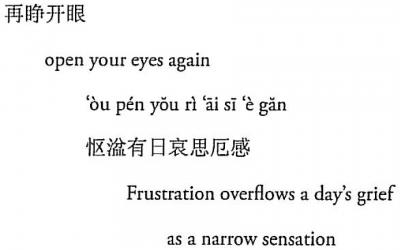

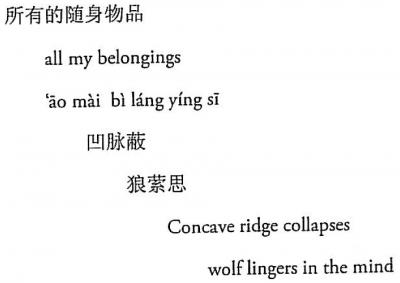

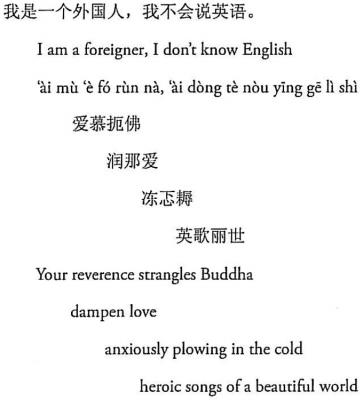

The format for each page of Yingelishi (which also bears the subtitle Sinophonic English Poetry and Poetics) includes five iterations: first, the phrase under consideration is presented in Chinese, then in English, and then in a transliteration of the English phrase as it will be heard and appear in Chinese; then, the English phrase appears in a Sinophonic (or homophonic) translation (in Chinese characters); and then the Chinese characters from the Sinophonic translation are translated into English. Here is a typical page:

What most amazes in this process – which sounds intricate, but when listened to, is quite easily apprehended – is when the simplest of phrases yields, through this process of sounding and re-sounding, a brief lyrical moment of great beauty:

What most amazes in this process – which sounds intricate, but when listened to, is quite easily apprehended – is when the simplest of phrases yields, through this process of sounding and re-sounding, a brief lyrical moment of great beauty:

Of course, one of the first phrases of use to a Chinese speaker beginning to learn English would be “I don’t know English.” In Yingelishi, that phrase (in a slightly more substantial version) becomes:

In the poem that introduces the book, Stalling indicates: “What emerges on the pages / is a figment of a transpacific imagination, / a dimly remembered dream of translingual consciousness / born in the strange half-light of cross-linguistic procreation.”

I have left the most astonishing aspect of Yingelishi for last: there is yet another transformation of this multilingual sounding. Stalling has been able to take these pages and have them become a libretto. An online supplement provides a full audio production of the work in two different readings: one with instrumentation and one without. After working with musicians and artists in Yunnan, Stalling was able to collaborate on a recording with a Chinese vocalist (Miao Yichen) who also plays the guzin on some tracks. A performance of the work took place on July 22, 2010, in the 15th-century Confucian Hall of Great Justice on the campus of Yunnan University.

Stalling’s plot summary helps us to track the narrative that emerges from sounding the multiple dimensions of a common phrase book: “an accented English libretto that tells the story of a Chinese speaker who uses Sinophonic English to negotiate the trials of traveling to and becoming lost in America, a tragedy in fact, since the protagonist is robbed soon after arriving in America and is left alone in an alien land with no friends, no money, no passport, and no way to understand the English language that appears to have swallowed her or him whole.” In this intersecting space of phrase book, chanted song, poem, and translations in multiple directions, “the accented voice that tells the story never fully becomes English because it never really stops being Chinese.” At the website, where you may listen to the opera, Stalling offers this explanation: “the English libretto of this ‘opera’ is written in Chinese, so when it is said aloud, the English speaker will hear an English poem, while a Chinese speaker will hear/read a series of Chinese poems, the poetry lies in the darkness between.”

Stalling’s plot summary helps us to track the narrative that emerges from sounding the multiple dimensions of a common phrase book: “an accented English libretto that tells the story of a Chinese speaker who uses Sinophonic English to negotiate the trials of traveling to and becoming lost in America, a tragedy in fact, since the protagonist is robbed soon after arriving in America and is left alone in an alien land with no friends, no money, no passport, and no way to understand the English language that appears to have swallowed her or him whole.” In this intersecting space of phrase book, chanted song, poem, and translations in multiple directions, “the accented voice that tells the story never fully becomes English because it never really stops being Chinese.” At the website, where you may listen to the opera, Stalling offers this explanation: “the English libretto of this ‘opera’ is written in Chinese, so when it is said aloud, the English speaker will hear an English poem, while a Chinese speaker will hear/read a series of Chinese poems, the poetry lies in the darkness between.”

Trust me: you will have a blissful, provocative 16:20 experience when you tune in to this intriguing operatic composition! For in the final analysis, I value Yingelishi so highly for the same reasons that I enjoy other forms of poetry: for the obvious integrity and thoughtfulness of the composition; for its adventurousness, beauty, and initial strangeness; and for the way that it repays re-reading and re-listening. Jerome Rothenberg, who calls Yingelishi “unprecedented,” finds that his reading and listening experience “grows deeper & richer from one immersion to the next. Yingelishi, once entered, has enough pleasures to last a reader’s lifetime.”

[Published June 15, 2011. 100 pages, paperback, $15.95.]

Hank Lazer’s seventeenth book of poetry, N18 (complete) will be published by Singing Horse Press in early 2012. N18 is part of a handwritten twenty-notebook project, The Notebooks (of Being & Time). For more about the shapewriting of the Notebooks, click here.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Elaine Sexton

Black Blossoms by Rigoberto González (Four Way Books)

The first word in Rigoberto González’s excellent collection is “strawberries,” followed by a stigmata, and in subsequent pages and poems: a red shirt, ruby heart, a red lake (as the lung of a bottle of cranberry juice), bleeding skulls, and more. It seems red is the dominant color fueling Black Blossoms, an encyclopedia of red, with gray playing second fiddle fusing a vivid succession of phantasmagorical poems with “the sutured centers of … gray vaginas,” “gray wings/ crushed into exotic fabrics too thin for winter,” elephant trunks, and a lover, whose “skin shades to gray.” A sweep of geographies from Mexico to Madrid, New York to Seattle carry these tightly structured narratives with references as far reaching as Otto Dix and Goya to Lizzie Borden and the Brothers Grimm. Peopled mostly by the stories of women – their struggles, their voices – each poem sings and stings with the dark heart of the familial, often employing the intimate triangulations of mother/father/child as characters mature but never leave their emotional baggage far behind. Betrayal, revenge, abandonment stain like watermarks.

The first word in Rigoberto González’s excellent collection is “strawberries,” followed by a stigmata, and in subsequent pages and poems: a red shirt, ruby heart, a red lake (as the lung of a bottle of cranberry juice), bleeding skulls, and more. It seems red is the dominant color fueling Black Blossoms, an encyclopedia of red, with gray playing second fiddle fusing a vivid succession of phantasmagorical poems with “the sutured centers of … gray vaginas,” “gray wings/ crushed into exotic fabrics too thin for winter,” elephant trunks, and a lover, whose “skin shades to gray.” A sweep of geographies from Mexico to Madrid, New York to Seattle carry these tightly structured narratives with references as far reaching as Otto Dix and Goya to Lizzie Borden and the Brothers Grimm. Peopled mostly by the stories of women – their struggles, their voices – each poem sings and stings with the dark heart of the familial, often employing the intimate triangulations of mother/father/child as characters mature but never leave their emotional baggage far behind. Betrayal, revenge, abandonment stain like watermarks.

In “Blizzard,” a speaker of unspecified gender, in the back seat of a car, relates to the news of another couple trapped by a storm, who “survived one week on saltine crackers and body heat.” And continues:

Mine is a tube of toothpaste in my bag and a man

in town who thanks me for opening my left nipple like a rose

at the prompting of his lips. When he turns his back to me

in bed his skin shades to gray and I know about the dead

who roll their eyes up to memorize the texture of their graves.

If I should freeze to death the muted explosion of my heart

will not betray me. The science of weather will have

its own sad story to tell when I am found, ten-fingered

fetus with a full set of teeth locked to a knucklebone.

In this book, the dead refuse to stay dead. The speakers are often women, as with seven of the poems that comprise the final section of the book. We hear from a mortician’s mother-in-law, his sister, his daughter, his Goddaughter, and step into their complex inner lives. In “The Mortician’s Bride Says I’m Yours,“ a confession:

As I rub my foot with oil I also mourn the pain

slowly vanishing. It’s one more precious possession gone.

Oh the devastating truth of loss, oh mercy. I have been

parting with myself since birth …

The 30 poems in Black Blossoms offer a sampler of magical realism, muscular syntax, and searing lament. Each voice inhabits gender, class, and historical context with an uncanny authority as the author shifts from poem to poem. Rigoberto González, who is also the author of a memoir, two novels, two bilingual children’s books, and a collection of short stories, is a wordsmith of the first order. He returns to poetry with this third collection, full of biting metaphors and memorable portraits, a singular pleasure to read.

The 30 poems in Black Blossoms offer a sampler of magical realism, muscular syntax, and searing lament. Each voice inhabits gender, class, and historical context with an uncanny authority as the author shifts from poem to poem. Rigoberto González, who is also the author of a memoir, two novels, two bilingual children’s books, and a collection of short stories, is a wordsmith of the first order. He returns to poetry with this third collection, full of biting metaphors and memorable portraits, a singular pleasure to read.

[Published October 11, 2011. 76 pages, $15.95 paperback]

Elaine Sexton’s poems and reviews have appeared in American Poetry Review, Art in America, Poetry, Pleiades, Oprah Magazine and elsewhere. Her most recent collection is Causeway (New Issues, 2008).

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Nick Sturm

I Am Not A Pioneer by Adam Fell (H_NGM_N Books)

The last page of Adam Fell’s I Am Not a Pioneer contains a transcript of a casual message from the poet to an anonymous friend with all of the names and specific references blacked out. The note, an unexpected afterword devoid of irony, is a touching mix of devotion, humor, profundity, modesty, and rawness that gets right at the busting, incongruent heart behind these poems. The following excerpt secures a belief that this collection instills early on, that this is the voice of a poet who wants to talk right into his readers, a voice that wants to be more than a voice, but a body, a being right next to you, another human stumbling and crashing against all this relentless, incredible confusion.

speaking of shitheel thoroughfares and Deadwood and Calamity, I keep thinking

what Jane says to Joanie in the first episode of the third season: Each day

takes learning all over again how to fucking live.

i have nothing to say about that. just wanted it here, for our record. Its

enough to just sit staggered for a moment. that’s all I really want. the briefest

flash of awe. like a tornado snapping power lines.

What we say and how we exist, Fell suggests, is a matter of having an intense, intimate relationship with our own human error. And what’s the error? Simply that we exist and are therefore fallible, compassionate, monstrous. The poems in I Am Not A Pioneer are built to both harness and magnify these errors, assembling a lot of god-awful, hope-ridden truths “for our record,” a conversation that is not only necessary, but that links us through all of the wreckage: “be safe and safe and safe,” Fell writes, “we need each other.”

What we say and how we exist, Fell suggests, is a matter of having an intense, intimate relationship with our own human error. And what’s the error? Simply that we exist and are therefore fallible, compassionate, monstrous. The poems in I Am Not A Pioneer are built to both harness and magnify these errors, assembling a lot of god-awful, hope-ridden truths “for our record,” a conversation that is not only necessary, but that links us through all of the wreckage: “be safe and safe and safe,” Fell writes, “we need each other.”

This need, this hope, is amalgamated and manifested throughout the book, as the obsessive force behind Fell’s poems. In “Friend Poem,” Fell questions the nature of absolute belief by presenting a kind of allegory in which a speaker imagines a friend being chased by religious zealots. Crossing a rope bridge over a river, the bridge collapses, throwing the whole group into the water.

And the religious zealots will crumple with me

and flail with me and when we descend into the river

together, they will no longer be religious zealots

but condensed packages of nutrient-rich materials

that will flow to the sea and become food

for the living snow that drifts

through the baleen of enormous creatures,

feeding those creatures and keeping them

safe and happy and full

in the collected deepness of their bodies.

After being dispersed back into the natural systems that both nourish us and guarantee our obliteration, ideological convictions are rendered inert and meaningless. No matter how much we think we know, the poem seems to suggest, our bodies will eventually give out, give themselves back to “the flooding world that is the collected / deepness of all of our bodies.” Though the ever-present prospect of our own destruction instigates fear and self-consciousness, it is exactly those moments of awareness that allow us to rally our hearts against the world’s indefatigable bullshit, ushering in a hope for the now, for this moment here, together, whether we’re hanging from the precipice or already washed away.

The poem “A Man Who Does Not Want to be Identified Nor Explain His Situation Sits Down” excavates even further into the body’s transience, pointing not only to individuals, but our culture at large, how it warps and consumes itself, paves over history, and in doing so, each of us. At a Native American site where “[i]n the recreational area, people are buried / in a mound in the shape of a heron,” the only thing that attracts the speaker’s attention are the “red lights of the cell tower across the river” in a “Wisconsin, emptied / of its old concussion of distance, // left with only the logic / of abandoned materials.” Having misplaced value with convenience, artifact with artifice, we are left cheapened, lost, though, as the poem suggests, we retain the ability to look back into ourselves where “[t]here is still life in the drainage of our skulls, / in our least love and cry and synapse.” Again, despite the forces arrayed against us, the hearts of these poems thrive.

However, the world of these poems is not always so broken. Every poem in I Am Not A Pioneer is rigged with at least one line whose images and juxtapositions ripple through the rest of the poem, triggering all kinds of emotional fall-out: “My cellular heart glows open. / Above me, sparrows, / make their nests in the skylights” (from “Near an Empty Fountain in the Foodcourt”); “I’m still hung-over / from two nights ago; // the lake is beautiful” (from “Ten Keys to Being a Champion On and Off the Field”); and “the sun [is] playing Wrestlemania / in the hallway of two mountains” (from “At Acadia National Park, The Morning of Peter Jennings’ Death”). Prizing recklessness over procedure, these poems light up with the urgency of their own being, making way for a contemporary imagination that is as buoyant as it is penetrating.

However, the world of these poems is not always so broken. Every poem in I Am Not A Pioneer is rigged with at least one line whose images and juxtapositions ripple through the rest of the poem, triggering all kinds of emotional fall-out: “My cellular heart glows open. / Above me, sparrows, / make their nests in the skylights” (from “Near an Empty Fountain in the Foodcourt”); “I’m still hung-over / from two nights ago; // the lake is beautiful” (from “Ten Keys to Being a Champion On and Off the Field”); and “the sun [is] playing Wrestlemania / in the hallway of two mountains” (from “At Acadia National Park, The Morning of Peter Jennings’ Death”). Prizing recklessness over procedure, these poems light up with the urgency of their own being, making way for a contemporary imagination that is as buoyant as it is penetrating.

Fueled by the compression of Fell’s language and his mastery of the line as a thing with which to twist and energize expectations, lines such as “[t]he cautious leaves of the city’s trees fall only / on those who need to be touched,” (from “Friend Poem”) reveal a world motivated by the kind of tenderness and compassion that lies in the background of many of these poems. “Slow Dance Slower” puts this dichotomy on display with the success of its music, describing how

Devotion extends forward

despite our bodies’ failures.

But our devotion, our devotion

is a doused thing of crumbling glow,

its human insides camouflaged

by our blackout city’s quieting coals.

Later in the poem, Fell describes how “we unfake our blood, // reach out to each other” as “[r]oses spill into the parking lot, / nuzzling sport utility vehicles.” Saturated with a kind of intolerable beauty, groping toward the hope of each other’s bodies, resilient in spite of themselves, these poems remind us that regardless of how horribly the world, or our own choices, dampen the celebration, each moment should be lived passionately, with risk, and with a compassion so immediate it hurts. I Am Not A Pioneer dances when it shouldn’t, quotes the Romantics on the nightly news, and is joyfully irreverent. “The moon pulls each wave to us,” Fell writes, “and taxes can never be taken out of that” (from “Ten Keys”). Adam Fell is asking us to occupy our hearts. It would not be a bad idea to rise to the task.

[Published May 1, 2011. 100 pages, $14.95 paperback]

Nick Sturm is a graduate student in the NEOMFA: Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts program. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Dark Sky, Forklift, Ohio, H_NGM_N, iO: A Journal of New American Poetry, Sixth Finch and TYPO.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Anna Journey

Money for Sunsets by Elizabeth J. Colen (Steel Toe Books)

“Let’s start with the alphabet,” suggests a woman in Elizabeth J. Colen’s prose poem, “The First Three Letters,” in order to persuade the speaker/new lover to memorize her name instead of a phone number. Colen writes:

What I didn’t say is that the mole is all she’ll leave

behind. Dark white behind my irises, a memory in negative. There’s a

whole ocean behind that spot and she’s making out letters on the page,

she’s watching them appear. Her name could be anything, I don’t trust

her. Her face rusts in my hands.

Cinematic, musical, fragmentary, and obsessively psychological, “The First Three Letters” embodies the larger project of Colen’s prose poetry collection Money for Sunsets (winner of the 2009 Steel Toe Books Prize in Poetry and recent nominee for the Lambda Literary Award): exploring the lyric capacity of the prose poem and the writer’s central preoccupations with loss and need in a restless bayside town. In Money for Sunsets we find lovers who no longer shower together because of the anger beneath one woman’s bathing gestures, children who live on a flood plain and lose their fingernails to water, a couple at a bar whose card game “resembles a dogfight on mute,” a remote chain smoking mother, and a moonshine-tipsy teen who holds her lover’s sandwich, “the dressing of which melted into the bag in the shape of Australia.” As Colen writes: “In this town nothing stays.”

Cinematic, musical, fragmentary, and obsessively psychological, “The First Three Letters” embodies the larger project of Colen’s prose poetry collection Money for Sunsets (winner of the 2009 Steel Toe Books Prize in Poetry and recent nominee for the Lambda Literary Award): exploring the lyric capacity of the prose poem and the writer’s central preoccupations with loss and need in a restless bayside town. In Money for Sunsets we find lovers who no longer shower together because of the anger beneath one woman’s bathing gestures, children who live on a flood plain and lose their fingernails to water, a couple at a bar whose card game “resembles a dogfight on mute,” a remote chain smoking mother, and a moonshine-tipsy teen who holds her lover’s sandwich, “the dressing of which melted into the bag in the shape of Australia.” As Colen writes: “In this town nothing stays.”

I’ve found the term “Lynchian” often arises in discussions of Colen’s collection. What does such a comparison mean, though, poetically speaking? Is it the poems’ grotesque imagery and psychological unease? Is it the book’s discomfiting sexual encounters? Is it the similarity between Colen’s Bellingham — the collection’s Pacific Northwestern backdrop — and Lynch’s fictional Twin Peaks? All of the above observations get close, but I’d like to arrive at a more particularized argument.

In the essay, “David Lynch Keeps His Head,” from A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, David Foster Wallace offers us a definition of “Lynchian”: “the term ‘refers to a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.’” The first sentence of Colen’s initial poem, “11 Bang-Bang,” perfectly illustrates Wallace’s notion of Lynchian: “Box of hair on a beach.” What at first seems a stylish absurdist fancy swiftly turns elegiac: “Scattered and new, ashes. A fine-feathered boy made of glass.” We discover a group of mourners have gathered on the beach to scatter the ashes of their friend, a war casualty (“11 Bang-Bang” is military slang for an infantryman). Colen’s final four sentences enact, through terse syntax, hypnotic assonance, and the repetition of images and phrases (the fragile “boy made of glass,” the saved hair, the box of ashes), the obsessive catalogues of grief, where there is no peripheral vision, only an unbearable focus on the inadequate substitutions for absence:

They wouldn’t let us see his

face. Scattered and torn, a boy made of glass, shattered. Golden hair

pressed into the child’s book of verse. Seared locks in a chocolate box,

the smell of candy and burn.

What’s particularly Lynchian, in this case, isn’t merely the strangeness of the poem’s dramatic conceit or the evocation of grotesque imagery; it’s the combination of the macabre (the charred hair of the dead soldier) with the mundane (the chocolate box) that creates a peculiarly unsettling, Lynchian sort of irony. It’s the “Seared locks” smell of slaughter contained within a cheerful grocery store package of confectionary: “the smell of candy and burn.” In the first third of the poem “Flood Plain,” Colen writes:

She was in love with the doorbell, the men who came, the orange

blossom scent the porch gave off when she reached to get the mail.

The car out front leaked oil and the pavement, which leaned into the

curb, was split by this thin blackness like the steep creek bed dividing

us from town.

It’s not the sharp contrast between the “orange blossom scent” of the porch and the “thin blackness” of leaking motor oil that make Colen’s poem Lynchian. It’s the way the daily goings-on of a lower income family separated from the town by a flood-prone creek take place amid the alarmingly grotesque: “We were so hungry then, our calluses yielding to yellowed teeth, nails coming off in the water.” Unlike the little girl who is “in love” with the men who appear to help the family during flood season, the child-speaker leans back, at the end of the poem, to observe the destruction and grows perversely enamored with the rising water’s transformative powers, “pleased at all the wet.”

It’s not the sharp contrast between the “orange blossom scent” of the porch and the “thin blackness” of leaking motor oil that make Colen’s poem Lynchian. It’s the way the daily goings-on of a lower income family separated from the town by a flood-prone creek take place amid the alarmingly grotesque: “We were so hungry then, our calluses yielding to yellowed teeth, nails coming off in the water.” Unlike the little girl who is “in love” with the men who appear to help the family during flood season, the child-speaker leans back, at the end of the poem, to observe the destruction and grows perversely enamored with the rising water’s transformative powers, “pleased at all the wet.”

Colen’s title poem sets forth a similarly giddy fable of destruction as two friends visit the beach and imagine the horizon’s “visible red line” an apocalyptic signal:

You grabbed rocks to fill your pockets in case it came to that. You

imagined wild dogs and truculent boys. Your jacket became bulky. I

thought better of it, thought less weight the way to go, in case the water

rose.

The Lynchian elements here involve two pals frolicking on a pier at sunset as they negotiate the best ways to properly drown oneself, with gusto:

The wind picked up. The seagulls played with it, unflappable

and grey in the last light. You were black against the red. I could not

see your eyes. You said, “I’d like to thank the academy,” and jumped

off into the waves.

Before the form of the prose poem became commonplace in contemporary letters, Baudelaire wrote to Arsène Houssaye about his dream of “the miracle of a poetic prose, musical, without rhythm and without rhyme, supple enough and rugged enough to adapt itself to the lyrical impulses of the soul, the undulations of reverie, the jibes of conscience.” Surely, Colen’s supple undulations and rugged jibes push the prose poem to its lyrical extremes, where, instead of Baudelaire’s derelict Paris, Colen leads us through her wayward bayside town where a suicide bows in front of a sunset and thanks the academy before leaping, where “wild dogs and truculent boys” abound, where “nothing stays.”

[Published June 1, 2010. 90 pages, $12.00 paperback]

Anna Journey is the author of the collection, If Birds Gather Your Hair for Nesting (Georgia, 2009), selected by Thomas Lux for the National Poetry Series. She holds a Ph.D. in creative writing and literature from the University of Houston, and recently received a fellowship in poetry from the NEA. She teaches creative writing at the University of Southern California.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Michael Collier

Coral Road by Garrett Hongo (Knopf) and Sand Theory by William Olsen (TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press)

Garrett Hongo in his lyrical memoir Volcano (1995) writes, “I had grown up in Los Angeles, hankering a little for Hawai’i all my childhood, had returned periodically, to O’ahu and my Kubota grandfather’s home there, in order to keep it part of my life.” By the time Hongo had written that passage he had already published two books of poems, Yellow Light (1982) and The River of Heaven (1988), both of which made increasingly detailed approaches to the material that would come fully alive in his memoir. Now, with the publication of the magnificent Coral Road, his first book of poems in twenty-three years, we see Hongo returning to O’ahu and his grandfather’s home on the North Shore in Kahuku, not only as memoirist and documentarian but as mythographer, cosmologist, and elegist.

Garrett Hongo in his lyrical memoir Volcano (1995) writes, “I had grown up in Los Angeles, hankering a little for Hawai’i all my childhood, had returned periodically, to O’ahu and my Kubota grandfather’s home there, in order to keep it part of my life.” By the time Hongo had written that passage he had already published two books of poems, Yellow Light (1982) and The River of Heaven (1988), both of which made increasingly detailed approaches to the material that would come fully alive in his memoir. Now, with the publication of the magnificent Coral Road, his first book of poems in twenty-three years, we see Hongo returning to O’ahu and his grandfather’s home on the North Shore in Kahuku, not only as memoirist and documentarian but as mythographer, cosmologist, and elegist.

Out of “hankering a little for Hawai’i in his childhood,” Hongo has made one of the most sublime and thoroughly modern renderings of Romantic recollection that can be found in American literature and he has done so by fusing the metaphysical lyricism of Emily Dickinson via Charles Wright with the materialist lyricism of Walt Whitman via Philip Levine. In this passage from “Kawela Studies” you can hear Wright (“Pipers scooting like feathered gray race-cars accelerating ahead, / The shark’s fin-and-tail in the surf the first plainsong of the morning, / Gloria of the bobbing turtle just offshore the second.” And with only a stanza break, he shifts tone so that we hear Wordsworth’s Prelude as well as Levine (“I came here once when I was nineteen and near fully a Mainland kid by then, / Slept shrouded on the beach in a GI-surplus mosquito net, smoked Camels and Marlboros / Days playing cards with cousins — nickel bets, peanuts, and pidgin all in the mix — / Dripping bottles of Primo beer our cold drink, raw fish salad our chaser.”

All throughout Coral Road there is a capaciousness and generosity as well as a scrupulousness of vision that is extremely rare in contemporary American poetry. The poems bear witness not only to the richness of cultures fractured by emigration and the attendant historical circumstances and vicissitudes that follow such fracturing but they also bear witness to the power of the obligation we feel to remember and revivify — restore — culture and family, and in this way all of Hongo’s work can be seen as an extended elegy. Listen to these lines from “Bugle Boys”: “As I am Kubota’s voice in this life, / chanting broken hymns to the sea, / So also am I my father’s hearing, / fifty-five now and three years shy of his age when he died, / My ears open as the mouth shells of two conchs, drinking in a soft, onshore wind.” It’s hard to imagine that a generation of poets has not had the opportunity to read a new book of poems by Garrett Hongo but Coral Road is certain to wake them up to his work as well as to the marvelous possibilities of his full-throated voice.

All throughout Coral Road there is a capaciousness and generosity as well as a scrupulousness of vision that is extremely rare in contemporary American poetry. The poems bear witness not only to the richness of cultures fractured by emigration and the attendant historical circumstances and vicissitudes that follow such fracturing but they also bear witness to the power of the obligation we feel to remember and revivify — restore — culture and family, and in this way all of Hongo’s work can be seen as an extended elegy. Listen to these lines from “Bugle Boys”: “As I am Kubota’s voice in this life, / chanting broken hymns to the sea, / So also am I my father’s hearing, / fifty-five now and three years shy of his age when he died, / My ears open as the mouth shells of two conchs, drinking in a soft, onshore wind.” It’s hard to imagine that a generation of poets has not had the opportunity to read a new book of poems by Garrett Hongo but Coral Road is certain to wake them up to his work as well as to the marvelous possibilities of his full-throated voice.

* * *

The “Theory” part of William Olsen’s utterly haunting new book is couched in propositions of belated joy. “This treasure,” he writes in “Dune Grass,” “so openly fragile it’s beginning / to dawn on me that we should all be singing.” Yes, “singing,” not crying, not solitary grieving but a celebration in recognizing the belatedness in everything, that, for example, “the lake is the ghost of a glacier, the clouds / are ghosts of the lakes.”

The “Sand” part is time, mortality, and the way it is seen in the shifting, refashioning landscapes of nature and human relationships: “For however much I meant to find human likeness / down on its knees, its hands churched together, / there’s more room than ever for the booming distances/ and sand enough for wind to blow beyond/ all of us who [are] abandoned” (“Dune Grass”).

The “Sand” part is time, mortality, and the way it is seen in the shifting, refashioning landscapes of nature and human relationships: “For however much I meant to find human likeness / down on its knees, its hands churched together, / there’s more room than ever for the booming distances/ and sand enough for wind to blow beyond/ all of us who [are] abandoned” (“Dune Grass”).

At times, Olsen’s consoling, calm, extravagant intensity sounds like Whitman, i.e., “I am a part of everything invisible.” “I turn myself away each night and day.” “I do not think it any different than midnight sky.” “I see myself disturb it with every step.” (“Sand Theory”). And while his ruminations may be prompted by the exterior world, by things, places, and people, they quickly and inevitably find their way to interior emotions and deep feeling. A Bachelard quotation that serves as an epigraph to “Cabbages Across from the Manitou Islands” — “the earth is the subconscious of the subconscious” — describes perfectly this interiority with its psychological and metaphysical penetration, a penetration that results in a profoundly spiritual agnosticism, as if nothing in experience proves or disproves the existence of god. In this way the poems are able to take the shape, literally and figuratively, of a pure, sublime, and deeply sincere response to everything Olsen encounters and, like Whitman, Olsen sees everything, down to the “tiniest corrugations on lake / pebbles showing from under, in cloud light, to cloud light, / in clarity, with clarity, as these clouds / gather the light of all the sunny days.” (“Sand Theory”).

Olsen has forged an idiom in Sand Theory that is so supple it accommodates a wide range of formal strategies, including prose poems and an intriguing fourteen-part, journal-like meditation, “Voice Road.” His syntax is instructive for its ever-branching clauses that suspend and delay the destination of their sentences and as such it is a model of a discursive mode handed down to him from Jon Anderson and Larry Levis.

Olsen has forged an idiom in Sand Theory that is so supple it accommodates a wide range of formal strategies, including prose poems and an intriguing fourteen-part, journal-like meditation, “Voice Road.” His syntax is instructive for its ever-branching clauses that suspend and delay the destination of their sentences and as such it is a model of a discursive mode handed down to him from Jon Anderson and Larry Levis.

William Olsen has always written thoroughly original books of poems, and Sand Theory is no exception, but it carries the force and insight of a life spent fashioning a language to match his experience and as a result we experience it as a moment of high achievement and also an indication of Olsen’s future work.

[Coral Road was published September 27, 2011. 120 pages, $26.00 hardcover. Sand Theory was published February 9, 2011. 96 pages, $16.95 paperback]

Michael Collier is the Director of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Maryland, an editorial consultant for poetry at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. His most recent book of poems is Dark Wild Realm (2006).

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Jennifer Barber

Ghost in a Red Hat by Rosanna Warren (W.W. Norton)

The poems in Rosanna Warren’s outstanding new collection, Ghost in a Red Hat, look hard at mortality, at the excesses of our society, and at the poet’s younger self. It’s as if Warren, known for her elegant lyricism, has dared herself to penetrate that lyricism in a new way. “Mistral I” is a case in point. The poem opens with a beautifully rendered landscape: “Two donkeys graze in a meadow of wild golden buttons. / Scents of eucalyptus and honeysuckle mingle in morning air.” Yet it isn’t long before the sun’s intensity starts to remind the poet of something else altogether:

… the sun bores into and into the petalled whorls of the golden flowers

like radiation, the whole meadow bristling with a heat that destroys and sustains.

The poet thinks of her friend who is undergoing radiation treatment; she hopes that the treatment will “let him grow into his longer story.” The landscape is no longer beauty made manifest; it has become associated in the poet’s mind and ours with a difficult biological truth.

Several poems in the collection reference the illness and death of the writer Deborah Tall, Warren’s close friend. “For D.” begins with a plane flight. The poet observes “…streaks/of creamy light through cumulus,” an image that rapidly transforms into a “mattress’s innards ripped.” Again we are not allowed to linger in a daydream of beauty; the reality of Tall’s illness will trump such impulses. The poem offers a persuasive portrait of a friendship that has lasted through the writing of many poems and the rearing of children and into middle age. But the two women, who have lived their lives in parallel, are suddenly in different “countries”:

Several poems in the collection reference the illness and death of the writer Deborah Tall, Warren’s close friend. “For D.” begins with a plane flight. The poet observes “…streaks/of creamy light through cumulus,” an image that rapidly transforms into a “mattress’s innards ripped.” Again we are not allowed to linger in a daydream of beauty; the reality of Tall’s illness will trump such impulses. The poem offers a persuasive portrait of a friendship that has lasted through the writing of many poems and the rearing of children and into middle age. But the two women, who have lived their lives in parallel, are suddenly in different “countries”:

… again I am making my way toward you

from the far country of my provisional health,

toward you in your new estate of illness, your suddenly acquired,

costly, irradiated expertise.

You have outdistanced me.

Both women are writers to their core, a fact that becomes abundantly clear in “Notes,” which describes one of their last phone calls, with Tall in a hospital room, Warren at a B & B “half a continent” away. Warren takes notes during their conversation “…in ink / so emphatically black it splodged / through to the other side of each notebook page” and says of Tall, “… You wanted / to finish your poems….” That one of the two should be facing death is something Warren struggles with in poem after poem, finally saying, in “Charon”: “Dear friend who spent years conjuring your ghosts, / how did you, so abruptly, join them?”

It is indicative of this collection’s range that poems of personal grief co-exist with poems that examine the larger culture. In “Earthworks,” Warren explores the life and vision of Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) as he undertakes the great project of creating Central Park. She imagines Olmsted imagining a place where “ward heelers, dandies, urchins, freed slaves, desperadoes/gents and ladies, the halt, the swift, the lame — / might come, might be drawn forth in courtesy, might // harmonize Democracy is space / in which we flow …”

In other poems, Warren provides contemporary glimpses of public spaces. In “Forty-second Street,” she says, “You could fall there among kegs and cardboard cartons/spiderwebs and planks The brokers and the broken // pass on the street…” In “After,” Warren describes New Orleans, post-Katrina: “The highway straight to end of the world skims past / a ruined mall, Kmart with roof stove in/acres of parking lots where weeds judder through cracks.” The devastating flood isn’t the only misfortune New Orleans is suffering from; the “acres of parking lots,” as for cities and towns all across the country, reveal a commercial culture hell-bent on stoking consumption. “Write an inventory, make an index, stutter a psalm,” the poet says, three acts that involve a reckoning with the ruins, both natural and manmade.

In other poems, Warren provides contemporary glimpses of public spaces. In “Forty-second Street,” she says, “You could fall there among kegs and cardboard cartons/spiderwebs and planks The brokers and the broken // pass on the street…” In “After,” Warren describes New Orleans, post-Katrina: “The highway straight to end of the world skims past / a ruined mall, Kmart with roof stove in/acres of parking lots where weeds judder through cracks.” The devastating flood isn’t the only misfortune New Orleans is suffering from; the “acres of parking lots,” as for cities and towns all across the country, reveal a commercial culture hell-bent on stoking consumption. “Write an inventory, make an index, stutter a psalm,” the poet says, three acts that involve a reckoning with the ruins, both natural and manmade.

The book’s masterful title poem employs a different kind of reckoning. The poet, in middle age and “of sensible girth,” looks back at her younger self: “I remember //starving. / I didn’t know why. // I practiced being a ghost.” And so we enter the mind of girl who has turned her intensity on herself and her body during a stay in Italy:

… it was picturesque, I was not

picturesque. That was the project:

I gnawed stale bread, roamed vineyards and olive groves,

drew portraits of artichoke plants under twisted trees,

recited Petrarch and grew

so thin I was a dazzling

knife blade in my new white pants.

The picturesque is never the whole story, the poet seems to be saying; it is only by admitting to the complexity of our past and current selves that we can begin to grapple with the bewildering nature of experience.

[Published March 28, 2011. 107 pages, $24.95 hardcover]

Jennifer Barber is the author of Given Away (forthcoming in 2012) and Rigging the Wind (2003), both from Kore Press. She edits Salamander at Suffolk University in Boston.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Joshua Weiner

Complete Poetry, Translations and Selected Prose by Bernard Spencer (Bloodaxe Books)

Have you heard of Bernard Spencer? I hadn’t. He’s not even included in the Oxford Anthology of Twentieth Century British and Irish Poetry, Keith Tuma’s monumental recovery project, which ten years ago reestablished the presence of an avant-garde in the more conventional narrative about modern poetry in the UK. Like Lynette Roberts, whom Tuma included and helped bring back into focus, Spencer was born in 1909. And as with Roberts, there’s a strong flavor of European modernism running through his work, though less obviously by virtue of disjunctive techniques (as one finds in her poems), and more in terms of a personal visionary quality, one that you might associate with Montale, Seferis, and Elytis, all poets he translated.

Born in Madras, India, he grew up in England, bumped shoulders with MacNeice and Spender and Auden (and Betjeman too), but was never of their circle. After college he spent most of his life abroad as a member of the British Council (Athens, Cairo, Turin, Madrid, Ankara, Vienna). His involvement in international modernism was as an intrepid stranger in communities where little English was spoken; at the same time, there’s something durably, intractably English about his poetry, a kind of intimately voiced prose element that recalls Edward Thomas, or the open rhythmical swing and naturalist surrealism of Ted Hughes.

Born in Madras, India, he grew up in England, bumped shoulders with MacNeice and Spender and Auden (and Betjeman too), but was never of their circle. After college he spent most of his life abroad as a member of the British Council (Athens, Cairo, Turin, Madrid, Ankara, Vienna). His involvement in international modernism was as an intrepid stranger in communities where little English was spoken; at the same time, there’s something durably, intractably English about his poetry, a kind of intimately voiced prose element that recalls Edward Thomas, or the open rhythmical swing and naturalist surrealism of Ted Hughes.

While in Egypt during World War II, he became part of a group in Cairo, associated with Lawrence Durrell and Keith Douglas, and edited an ex-pat magazine, Personal Landscape, issues of which have become collectors’ items. He’s seems quite clearly now to have been the best poet of the lot.

“Personal Landscape” is a phrase that captures some of the strongest qualities in Spencer’s poetry, which is often set in real locations, in particular situations, but from a solitary, idiosyncratic vantage conveyed in lines that unfold with a strong prose cadence and startling, mysterious images.

I first came across his poems about five years ago, when I was reading around in Edward Lucie-Smith’s Penguin paperback anthology, British Poetry since 1945 (1970), trying to fill in some mental mapping as I worked on a collection of essays about Thom Gunn. (I don’t much enjoy reading anthologies, but making these kinds of discoveries is one of the things they’re good for.) There were two poems tucked between W.S. Graham and Roy Fuller, “Night-time: Starting to Write” and “Properties of Snow.” The first begins:

Over the mountains a plane bumbles in;

down in the city a watchman’s iron-topped stick

bounces and rings on the pavement. Late returns

must be waiting now, by me unseen

To enter shadowed doorways. A dog’s pitched

barking flakes and flakes away at the sky.

Such writing immediately caught my ear (like that plane, buzzing into my personal space). The aural image of the doubled flakes is arresting, inventive, weird, and somehow natural to the sound of barking (the hard kays). There’s a formal shapeliness and ease, an attention to acoustic correspondences that is not insistent, or pedantic, but attentive though coolly engaged. A late-night suspension of floating-mind-in-preparation.

The second poem begins, “Snow on pine gorges can burn blue like Persian / cats; falling on passers can tip them with eloquent hair / of dancers or Shakespeare actors . . .” Who was this guy? The poems were more intimate and stranger than anything in the post-war period before 1955. Bold, sensitive, particular, quietly visionary, the poems have a sense of an individual breathing; one felt the coming-into-contact-with a heretofore unknown intriguing person — one of the deep appeals of reading new poetry. The poems sounded very contemporary.

A Collected Poems had appeared from Oxford in the early eighties. It was hard to find; there wasn’t much to go on. Now Bloodaxe has issued a new edition of Complete Poetry, including all of the translations and a good selection of prose (essays, interviews, notes, travel writing, an obituary for Keith Douglas), scrupulously edited by Peter Robinson. The best poems were written between 1947 and 1963, and are of immediate interest; the earlier stuff is somewhat in the key of Auden. But the volume as a whole is beautifully balanced in its portions, and reveals a poet who didn’t shake the world, but wrote honest, observant, often startling poems. He still gets unfairly pegged as a minor poet because he didn’t strain after big ideas, old mythologies or new ones, comprehensive social insights, or stylistic trickery. His feeling for poetry’s occasions places him more easily in a later generation; and in his prose he proves to be well appreciative of what younger poets in the late fifties had to offer. He died in 1963, under mysterious, odd circumstances. It was a terrible death-year for poetry: Frost, Williams, Plath, Roethke, Hikmet, MacNiece. By comparison, Spencer’s passing did not receive much notice. (He had published only two books.)

A Collected Poems had appeared from Oxford in the early eighties. It was hard to find; there wasn’t much to go on. Now Bloodaxe has issued a new edition of Complete Poetry, including all of the translations and a good selection of prose (essays, interviews, notes, travel writing, an obituary for Keith Douglas), scrupulously edited by Peter Robinson. The best poems were written between 1947 and 1963, and are of immediate interest; the earlier stuff is somewhat in the key of Auden. But the volume as a whole is beautifully balanced in its portions, and reveals a poet who didn’t shake the world, but wrote honest, observant, often startling poems. He still gets unfairly pegged as a minor poet because he didn’t strain after big ideas, old mythologies or new ones, comprehensive social insights, or stylistic trickery. His feeling for poetry’s occasions places him more easily in a later generation; and in his prose he proves to be well appreciative of what younger poets in the late fifties had to offer. He died in 1963, under mysterious, odd circumstances. It was a terrible death-year for poetry: Frost, Williams, Plath, Roethke, Hikmet, MacNiece. By comparison, Spencer’s passing did not receive much notice. (He had published only two books.)

If your interest in poetry is fed by tracing its role in cultural teleology, you probably won’t find time for him. He won’t fulfill anyone’s recovery agenda. But if you think of poems as companions through life, then he’s a good bet and worth getting to know.

[Published August 9, 2011. 352 pages, $34.95 paperback]

Joshua Weiner is the author of two books of poetry, The World’s Room and From the Book of Giants, and the editor of At the Barriers: On the Poetry of Thom Gunn (all from the University of Chicago Press). He teaches at University of Maryland and lives in Washington D.C.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Amanda Auchter

The Lifting Dress by Lauren Berry (Penguin)

I’ll admit it: being a Southerner, I love a good Southern Gothic. I was raised on Faulkner, O’Connor, Lee. Fortunately, Lauren Berry’s debut collection, The Lifting Dress (selected by Terrance Hayes as winner of the 2010 National Poetry Series Award), doesn’t disappoint. Keeping in the vein of other Southern Gothic writers, Berry’s poems weave mystery, coming-of-age, and familial dysfunction to create a narrative arc rife with tempered sensuality.

Berry’s poems in The Lifting Dress are brave and exacting. The collection builds from the moment after the speaker is raped and continues through the tumultuous fallout. In the first poem, “The Just-Bled Girl Refuses to Speak,” the speaker is being interviewed by a doctor who pleads with her to speak. Berry writes:

Like any panicked schoolgirl, I’m inarticulate

and constantly introduced

to beautiful things. Today it’s a doctor

who says, Young La-dy! and demands

Young La-dy, you cannot keep that garden

in your throat. How will we ask you questions?

How will you sip from the glass of water

and tell us what he did to you?

Berry’s skillful attention to line breaks here (and throughout the entirety of the collection) does exactly what line breaks are supposed to: create tension and subtle meaning. In this poem, Berry uses the line to juxtapose “beautiful things” with the doctor who is attempting to examine the speaker post-trauma. The outcome of this is striking: the speaker finds beauty — even in dark circumstances — in the doctor who wants to help her. There is much vulnerability in this work, and Berry’s poems work to create moment after moment of provocative confessions in the young speaker’s life.

Berry’s skillful attention to line breaks here (and throughout the entirety of the collection) does exactly what line breaks are supposed to: create tension and subtle meaning. In this poem, Berry uses the line to juxtapose “beautiful things” with the doctor who is attempting to examine the speaker post-trauma. The outcome of this is striking: the speaker finds beauty — even in dark circumstances — in the doctor who wants to help her. There is much vulnerability in this work, and Berry’s poems work to create moment after moment of provocative confessions in the young speaker’s life.

The Lifting Dress is filled with these striking moments where beauty meets the tragic. Take, for example, “Seventh Grade Science in the Partially Burned Classroom”:

I knew there were red wolves in my body, knew

what went past my lips was adding to me.

In the middle of the night, I’d wake in sweat

with a little more breast, already shifting

from the thing virgin in my skirt. I could leave her

in my skirt if I burned it.

There is a lot of red throughout The Lifting Dress: red wolves, the red carnation that fills the speaker’s throat in “The Just-Bled Girl Refuses to Speak.” Red, for Berry, is the color not just of the burgeoning passion of the speaker, but of danger, which is fitting for a collection so concerned with sexuality. In “Seventh Grade Science in the Partially Burned Classroom,” red becomes the wolves that live in the speaker’s body. Here, the wolves are the animals of desire that wake her—both literally and metaphorically—to the budding breasts, the burning skirt.

The speaker in Berry’s collection offers confession in a tone that does not seek pity, but instead gives insight into the vulnerability of a young woman who finds herself, among other things, alone with what she calls “The Big Man” in “Be a Good Girl, Don’t Tell.” In this, perhaps one of the most disturbing poems (and, it should be noted, disturbing in the Gothic-style) in the collection, the speaker lifts her head “from a man’s ink-stained hips / and attempted to tell him, / It tastes like poison.” Much like the speaker in “The Just-Bled Girl Refuses to Speak,” the speaker in “Be a Good Girl, Don’t Tell” cannot speak and instead wipes her tongue with a page from the telephone book. In this, the speaker devours the words she cannot utter in order to replace the man’s taste in her mouth. This single act is crux of Berry’s work in The Lifting Dress: how to reclaim the self through words when speech fails.

It seems like many first books by younger poets deal with coming-of-age to some degree, but Berry’s collection surpasses them by foregoing sweet boyfriends and loves lost in favor of a dark mythos that combines the vulnerability of a “hungry child, knelt // over smashed color” (“In The Abandoned Apartment Behind The Ice Cream Parlor”) with the triumph of a woman who, in the end, digs the carnation (“Revising What Is Mine”) from her throat in order to find the words that piece her life back together. In “My Father Takes Me Into The Backyard So I Can Become a Woman,” Berry pieces together a creation myth with the father as a “backyard priest” who drops stones into the daughter’s throat. Berry writes:

It seems like many first books by younger poets deal with coming-of-age to some degree, but Berry’s collection surpasses them by foregoing sweet boyfriends and loves lost in favor of a dark mythos that combines the vulnerability of a “hungry child, knelt // over smashed color” (“In The Abandoned Apartment Behind The Ice Cream Parlor”) with the triumph of a woman who, in the end, digs the carnation (“Revising What Is Mine”) from her throat in order to find the words that piece her life back together. In “My Father Takes Me Into The Backyard So I Can Become a Woman,” Berry pieces together a creation myth with the father as a “backyard priest” who drops stones into the daughter’s throat. Berry writes:

Father yes. I’m a body of water now. I am stones and I am swamp and I sink

children under the weight of my river, rinse blood from their tongues.

I take a sip of water. He drops a stone into my throat. I take a sip of water.

What am I made of when he says, Watch how your body endures?

The body endures much in Berry’s collection. At every turn, there is danger, even in one’s own house as in “The Big Man Visits His Landlord’s Daughter” where a sister’s tooth hangs from a doorknob by dental floss. Berry’s use of specificity, however direct and at times, yes, disturbing, is spot-on and gives voice to a world as lovely as it is damaged.

“Words are the poison I name,” Berry writes in “Be a Good Girl, Don’t Tell.” These poems push “against / the places [we’re] never allowed into” (“In The City Parking Lot, The Last Night”). This collection is filled with the energy of words that allows a glimpse into an otherwise private world of budding sexuality, taboo, and familial dysfunction. Berry has given us a book that, as in “In The City Parking Lot, The Last Night,” untwists the chains of girlhood in order to realize that “the holiness of childhood is heavy.” In this, The Lifting Dress is an exciting debut that offers honesty and above all, beauty.

[Published May 31, 2011. 80 pages, $16.00 paperback]

Amanda Auchter is the founding editor of Pebble Lake Review and the author of The Glass Crib, recipient of the 2010 Zone 3 Press First Book Award judged by Rigoberto González. She holds an MFA from Bennington College and teaches creative writing and literature at Lone Star College.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Brian Teare

Kintsugi by Thomas Meyer (Flood Editions)

Let’s suppose an elegy might contain any or all of the following: an account of the deceased; the facts of their death; descriptions of the elegist’s grief; a meditation on the larger implications of the death of the deceased and of death in general. Let’s also suppose that — depending upon the poet, the historical period and culture, and the identity of the deceased — the elegy’s larger occasion might be theological or philosophical reflection, biographical tribute or autobiographical narrative, or an investigation into the nature of language as a medium for grief. Let’s also make it safe to suppose that the elegiac text might also perform the traditional ritual duty of consolation by attempting to repair the tear left behind in the social fabric by death.

Let’s suppose an elegy might contain any or all of the following: an account of the deceased; the facts of their death; descriptions of the elegist’s grief; a meditation on the larger implications of the death of the deceased and of death in general. Let’s also suppose that — depending upon the poet, the historical period and culture, and the identity of the deceased — the elegy’s larger occasion might be theological or philosophical reflection, biographical tribute or autobiographical narrative, or an investigation into the nature of language as a medium for grief. Let’s also make it safe to suppose that the elegiac text might also perform the traditional ritual duty of consolation by attempting to repair the tear left behind in the social fabric by death.

Given these suppositions, I’d like to argue that the elegy’s already complex generic tropes are made differently complicated when the one who has died is a lover or long-time companion. Because eros in its largest sense is epistemological, a way of knowing self and other and the real, the loss of the beloved to death constitutes a wound to how the elegist knows not only the deceased, but also her/himself and the real—this wound is especially deep if the elegist’s experience and concept of eros have not fully accounted for the fact of death. What gives elegy and its language their intensity is that they are ultimately the way a tree in time has grown over the barbwire that once enclosed it: though mourning is a form of healing, to know the world after elegy is paradoxically to know that erotic knowledge integrates into itself the shape of what’s wounded it.

A memorial to poet and publisher Jonathan Williams, Thomas Meyer’s partner of almost forth years, Kintsugi is a particularly moving example of elegy as a registration of the wound dealt by death to an erotic epistemology. “Kintsugi” is the Japanese practice of using gold-laced lacquer to repair broken ceramics, and Meyer places a definition of the word on the page preceding the first poem, a placement that practically guarantees readers experience the poems metaphorically. But it is an elegant metaphor for elegiac practice — a careful repair of erotic fragments — and as Meyer suggests at the conclusion of “New Poem,” the book’s penultimate poem, the elegy’s shattered vessel can’t help but function as a substitute:

Once when the poem

was a bright, shiny thing, think

what it could or would do …

The logical conclusion

is that

everything that goes

wants to be

its place holder.

If loss creates a profound confusion between what is lost and what the elegist substitutes for the one lost to death, kintsugi as a metaphor likewise begs the question of tenor and vehicle. Clearly the poet is the ceramicist, but is the poem the lacquer and the real the broken vessel? Is the real the lacquer and the poem the broken vessel? Is the elegy’s epistemology the lacquer and the past the broken vessel? Or is the elegy’s epistemology the lacquer and the body of the deceased the broken vessel? Given that “everything that goes/wants to be/its place holder,” this game of substitution can go on and on, a fact that suggests both the richness of Meyer’s chosen metaphor and the canniness of his choice to let all possible tenor and vehicle relationships remain in play.

Most attentive to the mind in mourning and to the mind mourning in language, Meyer allows the seven poems of Kintsugi to forgo narrative, sequential and discursive completeness in favor of voicing “The call that goes unanswered.” “To talk with the dead about desire,” Meyer asks late in the book, “Is that / what the poem has left us?” Prioritizing the fragmentary and haunted quality of elegiac epistemology, Meyer’s poems don’t attend to the generic tropes of elegy so much as invoke them as a collateral of the mourning mind. Thus elegy plays out most concretely in the sensibility of the poet, a seismograph calibrated to the smallest of tremors: “not rhetoric or suddenness, but a/quickening of moonlight if that can be imagined.” What I love most about Kintsugi’s performance of elegiac epistemology is its juxtaposition of imagistic precision with fragments of rhetoric and narrative, as though the mind were at once transcribing and describing and revising, as at the opening of “Open Window,” the volume’s third poem:

Most attentive to the mind in mourning and to the mind mourning in language, Meyer allows the seven poems of Kintsugi to forgo narrative, sequential and discursive completeness in favor of voicing “The call that goes unanswered.” “To talk with the dead about desire,” Meyer asks late in the book, “Is that / what the poem has left us?” Prioritizing the fragmentary and haunted quality of elegiac epistemology, Meyer’s poems don’t attend to the generic tropes of elegy so much as invoke them as a collateral of the mourning mind. Thus elegy plays out most concretely in the sensibility of the poet, a seismograph calibrated to the smallest of tremors: “not rhetoric or suddenness, but a/quickening of moonlight if that can be imagined.” What I love most about Kintsugi’s performance of elegiac epistemology is its juxtaposition of imagistic precision with fragments of rhetoric and narrative, as though the mind were at once transcribing and describing and revising, as at the opening of “Open Window,” the volume’s third poem:

Sudden flicker. Light, late afternoon. Bird. But

in that instance something expected. Some one

or thought. Gone. Here then not. The air

holds its shape a moment more. An instant

outlasts its own emptiness …

In Chinese a hand reaches for the moon

to mean “have” or commonly “be.”

To have to be. Or not. Grab

the moon or blot out its light.

There’s no timing to these things.

Unless it’s all timing. A beat impossible

to catch …

Thus time and timing play a defining role in Meyer’s rendering of elegiac epistemology: the elegy is always essentially belated, its language a reach that grabs nothing but the ambient qualities of after. “What / had I expected? Ghosts? Haunted details?,” the poem “Endings” asks before answering itself: “I don’t know. Unless loss does away / with the previous itself. It must.” The essential tragedy of after is that the elegist’s sense of being in time has been wounded by death in the way that a syncope is a heart attack as well as an off-beat rhythm. Such syncopations find their way into the book not only through a tendency toward stuttering self-interrogations and -corrections, but also through images touched upon briefly in one poem and returned to in passing in another. “Open Window” is the title of one poem, and “Open Door” another, and these phrases, among many others, return in the poems as images and phrases. Such echoes constitute a kind of delayed, rhythmic off-rhyme, not unlike the one between “waiting” and “wanting” that Meyer most favors. Take this passage from later in “Open Window”:

Open book. No, open door. But why not?

Book. Door. Table. Chair. Blank

slate. Book. Over and over until there

is no over. The mind, the heart—whatever

holds—runs out …